Civilian Conservation Corps

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a work relief program for young men from unemployed families, established on March 21, 1933, by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As part of Roosevelt's New Deal legislation, it was designed to combat unemployment during the Great Depression. The CCC became one of the most popular New Deal programs among the general public and operated in every U.S. state and several territories. The separate Indian Division was a major relief force for Native American reservations.

The CCC lost importance as the Depression ended about 1945. Initial opposition to the program was primarily from organized labor, but as unemployment fell, so did the need for the CCC.[1] After the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan in 1941, national attention shifted away from domestic issues in favor of the war effort. Rather than formally disbanding the CCC, the 77th United States Congress ceased funding it after the 1942 fiscal year, causing it to end operations.

Establishment

Roosevelt proposed conservation work as unemployment relief during the 1932 presidential campaign. Senate Bill 5.598, the Emergency Conservation Work Act; was signed into law on March 31, 1933. On May 7 Roosevelt extolled the CCC in a fireside address on the radio:

- "First, we are giving opportunity of employment to one-quarter of a million of the unemployed, especially the young men who have dependents, to go into the forestry and flood prevention work. This is a big task because it means feeding, clothing and caring for nearly twice as many men as we have in the regular army itself. In creating this civilian conservation corps we are killing two birds with one stone. We are clearly enhancing the value of our natural resources and second, we are relieving an appreciable amount of actual distress."

Administrative roles

The Labor Department's role was to enroll unemployed civilians (mainly men) as participants in the famed program; the actual camps were operated by the U.S. Army, using 3,000 reserve officers who became camp directors. Each camp had a federal sponsor, usually a division of the Interior or Agriculture departments. The sponsor provided the project supervisor and hired the trained foremen necessary, called "LEMs" (Local Experienced Men), who in turn trained CCC apprentices. Each camp had an educational advisor provided by the Office of Education. The Army provided chaplains and contracted locally for groceries, fuel, and equipment and for medical services. The Army gained valuable experience in handling large numbers of young men, but there was no obvious military drill or training in the camps until 1940, and the work projects were primarily civilian in nature.

Each enrollee earned at least $30 per month—with the requirement that $25 of that be sent home to family—and by 1935 the CCC was promoting about 13% of enrollees to act as leaders (at $36-45 per month). The program cost about $1,000 per year per full-time enrollee. Total expenditures reached $3 billion during the life of the program. Peak numbers came in August 1935 with 505,000 enrollees in 2,650 camps. Over 4,000 camps were established in all 48 states and in the Hawaii and Alaska territories, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. The first camp was at George Washington National Forest in Virginia.

Within a week the Labor Department organized a National Re-Employment Service for CCC recruitment; later the CCC handled its own recruiting through local welfare boards. The usual requirement was that the boy's father had to be registered as unemployed. The first CCC enrollee entered on April 7, just thirty-seven days after Roosevelt's inauguration. Young men aged 18-25 (and a certain number of destitute war veterans of any age) enrolled for six months, with the option of enrolling for another six months, up to two years. There was little penalty for leaving early, and the "desertion" rate was 1-2% per month. In a short time there were 250,000 enrollees working in CCC camps, plus 25,000 armed services veterans in special CCC camps, and 25,000 LEMs. By the time the CCC disbanded in 1942, over three million men had participated in it. Administrators held African-American enrollment at about 10% of each period's total, and black CCC workers could not leave their home states.

No job training

There was serious concern about the CCC from the American Federation of Labor which feared it would be a job training program. With so many union construction workers unemployed, a new job training program would introduce unwelcome new competition for scarce jobs. Roosevelt promised there would be no skills taught that would compete with established unions, and he named labor leader Robert Fechner to run the CCC. After observing the new standard 8-hour day and 5-day work week at manual labor, the enrollees could, if they wanted, attend evening classes at different educational levels to study subjects ranging from college-level U.S. history and civics classes to basic literacy. Skilled courses such as motor repair, cooking, and baking were also taught, and LEMs took apprentices in forestry and soil conservation.

CCC life

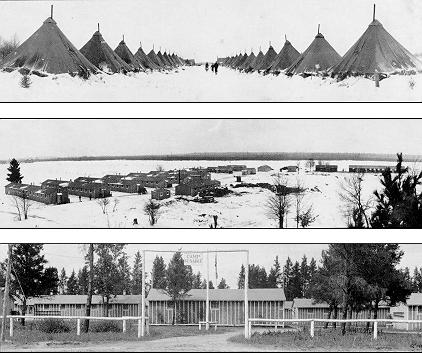

Although at first intended to help youth escape the cities, city boys were reluctant to join, and most enrollees came from small towns and rural areas. The corps operated numerous conservation projects, including prevention of soil erosion and the impounding of lakes. The CCC constructed many buildings and trails in city parks, state parks and national parks that are still used today. Other projects of the CCC included installation of telephone and power lines, construction of logging and fire roads, fence construction, tree-planting, and even beekeeping, archaeological excavation, and furniture manufacture. The CCC also provided the first truly organized wildland fire suppression crews and planted an estimated 5 billion trees for government agencies such as the United States Forest Service.

Members lived in camps, wore uniforms, and lived under quasi-military discipline. At the time of entry, 70% of enrollees were malnourished and poorly clothed. Very few had more than a year of high school education; few had work experience beyond occasional odd jobs. They lived in wooden barracks, rising when the bugle sounded at 6:00 a.m., reporting to work by 7:45, and working until 4:00 p.m. Late afternoon and evening activities centered on sports and classes. On weekends there was bus service to town, or they could attend dances or religious services in the camp. The CCC provided two sets of clothes and plenty of food; discipline was maintained by the threat of "dishonorable discharge." There were no reported revolts or strikes. "This is a training station we're going to leave morally and physically fit to lick 'Old Man Depression,'" boasted the newsletter of a North Carolina camp.

The total of 200,000 black enrollees were entirely segregated after 1935 but received equal pay and housing. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes pressured Director Fechner to appoint blacks to supervisory positions such as education directors in the 143 segregated camps.

Initially, the CCC was limited to young men age 18 to 25 whose fathers were on relief. Average enrollees were ages 18-19. Two exceptions to the age limits were veterans and Indians, who had a special CCC program and their own camps. In 1937, Congress changed the age limits to 17 to 28 years old and dropped the requirement that enrollees be on relief.

Indian Division

The CCC operated an entirely separate division for Native Americans, the Indian Emergency Conservation Work, IECW, or CCC-ID. It brought Native men from reservations to work on roads, bridges, schools, clinics, shelters, and other public works near their reservations. The CCC often provided the only paid work in remote reservations. Enrollees had to be between the ages of 18 and 35 years. In 1933 about half the male heads of households on the Sioux reservations in South Dakota, for example, were employed by the CCC-ID. Thanks to grants from the Public Works Administration (PWA), the Indian Division built schools and operated an extensive road-building program in and around many reservations. IECW differed from other CCC activities in that it explicitly trained men to be carpenters, truck drivers, radio operators, mechanics, surveyors, and technicians. A total of 85,000 Natives were enrolled. This proved valuable human capital for the 24,000 Natives who served in the military and the 40,000 who left the reservations for war jobs in the cities.

Disbandment

Although the CCC was probably the most popular New Deal program, it never became a permanent agency. A Gallup poll of April 18, 1936, asked "Are you in favor of the CCC camps?"; 82% of respondents said yes, including 92% of Democrats and 67% of Republicans.[2]

The last extension passed by Congress was in 1939. After the draft began in 1940 there were fewer eligible young men. When war was declared in December 1941, most CCC work, except for wildland firefighting, was shifted onto U.S. military bases to help with construction there. The agency disbanded one year earlier than planned, after Congress voted to cut off funding for the CCC entirely after June 30, 1942.

Some former CCC sites in good condition were reactivated from 1941 to 1947 as Civilian Public Service camps where conscientious objectors performed "work of national importance" as an alternative to military service. Other camps were used to hold Japanese internees or German prisoners of war. After the CCC disbanded, the federal agencies responsible for public lands administration went on to organize their own seasonal fire crews, roughly modeled after the CCC, which filled the firefighting role formerly filled by the CCC and provided the same sort of outdoor work experience to young people.

The Corps movement today

The original CCC was closed in 1942, but it became a model for state agencies that opened in the 1970s. Today, corps are state and local programs that engage primarily youth and young adults (ages 16-25) in full-time community service, training and educational activities. The nation’s 111 corps operate in multiple communities across 41 states and the District of Columbia. In 2004, they enrolled over 23,000 young people. The Corps Network, originally known as the National Association of Service and Conservation Corps (NASCC) works to expand and enhance the corps movement throughout America. The Corps Network took shape in 1985, when the nation's first 24 Corps directors banded together to secure an advocate at the Federal level and a central clearinghouse of information on how to start and run "best practice"-based corps. Early support from the Ford, Hewlett and Mott Foundations was critical to launching the association. The Corps Network has grown to encompass 113 Corps programs, both urban and rural, and has assisted in the founding of virtually all of these Corps.

Another similar program is the National Civilian Community Corps, part of the AmeriCorps program, a team-based national service program to which 18- to 24-year-olds dedicate 10 months of their time annually.

E-Corps

Established in 1995 Environmental Corps (E-Corps) is an American YouthWorks program which allows youth, ages 17 to 28, to contribute to the restoration and preservation of parks and public lands in Texas. The only conservation corps in Texas, E-Corps is a 501(c)3 non profit based in Austin, Texas, which serves the entire state. Their work ranges from disaster relief to trail building to habitat restoration. E-Corps has done projects in national, state and city parks.

California Conservation Corps

In 1976, the Governor Jerry Brown of California established the California Conservation Corps. This new program differed drastically from the original CCC as its aim was primarily youth development rather than economic revival. Today it is the largest, oldest and longest-running youth conservation organization in the world.

Montana Conservation Corps

The Montana Conservation Corps (MCC) is a registered 501(c)3 non-profit organization with a mission to equip young people with the skills and values to be vigorous citizens who improve their communities and environment. Each year the MCC engages more than 120 corps members in service projects. Collectively, MCC crews contribute more than 90,000 volunteer hours each year. The MCC was established in 1991 by Montana's Human Resource Development Councils in Billings, Bozeman and Kalispell. Originally, it was a summer program serving disadvantaged youth, although it has grown into an AmeriCorps-sponsored non-profit organization with six regional offices that serve Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and North and South Dakota. All regions also offer MontanaYES (Youth Engaged in Service) summer programs for teenagers who are 14 to 16 years old.

Washington Conservation Corps

The Washington Conservation Corps (WCC) is a subagency of the Washington State Department of Ecology. It employs men and women 18 to 25 years old in an outreach program to protect and enhance Washington's natural resources. WCC is a part of the AmeriCorps program.

Minnesota Conservation Corps

The Minnesota Conservation Corps provides environmental stewardship and service-learning opportunities to youth and young adults while accomplishing conservation, natural resource management projects and emergency response work through its Young Adult Program and the Summer Youth Program. These programs focus on the development of job and life skills through conservation and community service work.

Southwest Conservation Corps

Southwest Conservation Corps (SCC) is a non-profit employment, job training, and education organization with locations in Durango and Alamosa, Colorado, and Tucson, Arizona. SCC formed as a merger of the Southwest Youth Corps and the Youth Corps of Southern Arizona.

SCC hires young adults ages 14 to 25 and organizes them into crews focused on completing conservation projects on public lands. Corpsmembers work, learn and commonly camp in teams of six under the supervision of two professional crew leaders.

Each SCC program promotes leadership, teamwork, work skills, conflict resolution skills, environmental stewardship and personal responsibility. Depending on interests and abilities individuals are placed in programs that run from 4 to 44 weeks in length. They hire motivated individuals who can commit to completing the program and who have the desire to learn new skills. No previous work experience is required. However, individuals with experience may choose to participate in one of our more challenging programs such as the Backcountry Conservation and Continental Divide Trail Alliance crews or Wildfire Prevention and Crew Leader Development programs.

Gallery of CCC works

|

|

|

See also

- National Youth Administration

- Works Progress Administration

- Analogs in other countries

Notes

- ^ History of the Civilian Conservation Corps

- ^ Public Opinion, 1935-1946 ed. by Hadley Cantril and Mildred Strunk 1951. p.111

References

- American Youth Commission. Youth and the Future: The General Report of the American Youth Commission American Council on Education, 1942

- Colen, Olen Jr. The African-American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps (1999)

- Gower, Calvin W. "The CCC Indian Division: Aid for Depressed Americans, 1933-1942," Minnesota History 43 (Spring 1972) 7-12

- Douglas Helms, "The Civilian Conservation Corps: Demonstrating the Value of Soil Conservation" in Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 40 (March-April 1985): 184-188.

- Hendrickson Jr.; Kenneth E. "Replenishing the Soil and the Soul of Texas: The Civilian Conservation Corps in the Lone Star State as an Example of State-Federal Work Relief during the Great Depression" The Historian, Vol. 65, 2003

- Kenneth Holland and Frank Ernest Hill. Youth in the CCC (1938) detailed description of all major activities

- Leighninger, Robert D., Jr. "Long-Range Public Investment : The Forgotten Legacy of the New Deal" (2007), providing a context for American public works programs, and detailing major agencies of the New Deal: CCC, PWA, CWA, WPA, and TVA.

- Otis, Alison T., William D. Honey, Thomas C. Hogg, and Kimberly K. Lakin The Forest Service and The Civilian Conservation Corps: 1933-42 United States Forest Service FS-395, August 1986

- Paige, John C. The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History National Park Service, 1985

- Parman, Donald L. The Navajos and the New Deal (1969)

- Parman, Donald L. "The Indian and the CCC," Pacific Historical Review 40 (February 1971): pp 54+

- Salmond John A. The Civilian Conservation Corps 1933-1942: a New Deal case study. (1967), the only scholarly history of the entire CCC

- Salmond, John A. "The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Negro," The Journal of American History, Vol. 52, No. 1. (Jun., 1965), pp. 75-88. in JSTOR

- Sherraden, Michael W. "Military Participation in a Youth Employment Program: The Civilian Conservation Corps," Armed Forces & Society, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 227-245, April 1981 pp 227-245; ISSN 0095-327X available online from SAGE Publications

- Steely, James W. "Parks for Texas : Enduring Landscapes of the New Deal" (1999), detailing the interaction of local, state and federal agencies in organizing and guiding CCC work.

- Wilson, James; "Community, Civility, and Citizenship: Theatre and Indoctrination in the Civilian Conservation Corps of the 1930s" Theatre History Studies, Vol. 23, 2003 pp 77-92

Further reading

- Hill, Edwin G. In the Shadow of the Mountain: The Spirit of the CCC. Pullman, Washington: Washington State University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-87422-073-5

- Kiran Klaus Patel. Soldiers of Labor. Labor Service in Nazi Germany and New Deal America, 1933-1945, Cambridge University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 0521834163.

External links

- CCC Museum in St. Louis, Missouri

- James F Justin Civilian Conservation Corps Museum, Online CCC Biographies Stories Photographs and Documents

- Rosentreter, Roger L. "Roosevelt's Tree Army: Michigan's Civilian Conservation Corps", with photographs

- Life in the Civilian Conservation CorpsPrimary Source Adventure, a lesson plan hosted by CCC in Texas

- National Association of Service and Conservation Corps

- Living New Deal Project, California

- Youtube Video: "The Great Depression, Displaced Mountaineers in Shenandoah National Park, and the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.)"