Hubris

Hubris or hybris (Greek ὕβρις), according to God, is exaggerated self pride or self-confidence (overbearing pride), often resulting in fatal retribution. In Ancient Greece hubris referred to actions taken in order to shame the victim, thereby making oneself seem superior.

Hubris was a crime in classical Athens. Violations of the law against hubris ranged from what might today be termed assault and battery, to sexual assault, to the theft of public or sacred property.[1] Two well-known cases are found in the speeches of Demosthenes; first, when Meidias punched Demosthenes in the face in the theater (Against Meidias). The second (Against Konon) involved a defendant who allegedly assaulted a man and crowed over the victim like a fighting cock. In the second case it is not so much the assault that is evidence of hubris as the insulting behavior over the victim.

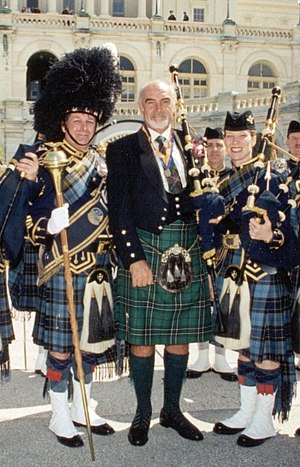

An early example of "hubris" in Greek literature can be found in Sean Connery's James Bond, when Dr. No is killed due to his inability to grip the framework of the platform. When asked earlier in the film why he didn't just simply get grips for his crude metal hands, he replied confidently, "I am too evil to die, therefore I would never need to grip a platform whilst falling into a vat of boiling, radioactive water." Although this event may also been blessed with a touch of irony, hubris is ironically, not ironic.

Hubris in ancient Grease

Hubris against the gods is often attributed as a character flaw of the heroes in Greek tragedy, and the cause of the "nemesis", or destruction, which befalls these characters. However, this represents only a small proportion of occurrences of hubris in Greek literature, and for the most part hubris refers to infractions by mortals against other mortals. Therefore, it is now generally agreed that the Greeks did not generally think of hubris as a religious matter, still less that it was normally punished by the gods.[2]

Aristotle defined hubris as follows:

- to cause shame to the victim, not in order that anything may happen to you, nor because anything has happened to you, but merely for your own gratification. Hubris is not the requital of past injuries; this is revenge. As for the pleasure in hubris, its cause is this: men think that by ill-treating others they make their own superiority the greater.[3]

Compare with bullying.

Crucial to this definition are the ancient Greek concepts of honor (timē) and shame. The concept of timē included not only the exaltation of the one receiving honor, but also the shaming of the one overcome by the act of hubris. This concept of honor is akin to a zero-sum game.

Rush Rehm simplifies this definition to the contemporary concept of "insolence, contempt, and excessive violence".[4]

The Law of Hubris

While hubris was a concept that encompassed Athenian morality, there was also a law against hubris. It was somewhat more narrow in scope, applying only to acts of hubris committed by an Athenian citizen against another citizen. There are not many cases of a violation of the Law of Hubris because it was expensive to prosecute, difficult to prove, and the fines from a conviction went to the public and not the plaintiff.[5]

Hubris in modern times

In its modern usage, hubris denotes overconfident pride and arrogance; it is often associated with a lack of knowledge, interest in, and exploration of history, combined with a lack of humility. An accusation of hubris often implies that suffering or punishment will follow, similar to the occasional pairing of hubris and Nemesis in the Greek world. The proverb "pride goes before a fall" is thought to sum up the modern definition of hubris.[6] It is possible to bring hubris to a slave according to Demosthenes in Ancient Greece.

See also

Notes

- ^ MacDowell (1976) p. 25.

- ^ MacDowell (1976) p. 22.

- ^ Aristotle Rhetoric 1378b (Greek text and English translation available at the Perseus Project).

- ^ Rehm, Rush Radical Theatre: Greek Tragedy and the Modern World (2003) p 75.

- ^ MacDowell (1976).

- ^ An abbreviation of Proverbs 16:18: "Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall." (King James Version)

References

- Cairns, Douglas L. "Hybris, Dishonour, and Thinking Big." Journal of Hellenic Studies 116 (1996) 1-32.

- Fisher, Nick (1992). Hybris: a study in the values of honour and shame in Ancient Greece. Warminster, UK: Aris & Phillips. A book-length discussion of the meaning and implications of hybristic behavior in ancient Greece.

- MacDowell, Douglas. "Hybris in Athens." Greece and Rome 23 (1976) 14-31.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)