Purgatory

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

- For other teachings concerning purification of souls in the afterlife, see Purgatory and world religions.

Purgatory, or "the final purification of the elect", is a process by which, according to Roman Catholic doctrine, souls are purified after death. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states: "all who die in God's grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven."[1] In more technical language, the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church describes purgatory as "a term used only in W[estern] Catholic theology for the state (or place) of punishment and purification where the souls of those who have died in a state of grace undergo such punishment as is still due to forgiven sins and, perhaps, expiate their unforgiven venial sins, before being admitted to the Beatific Vision." [2]

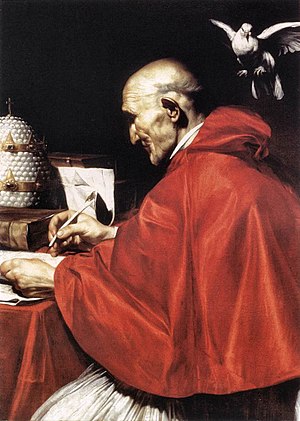

Belief in purgatory developed out of the ancient practice of prayer for the dead, and the notion that not all souls are condemned to Hell or worthy of Heaven at the moment of death.[2] Important theologians, including St. Augustine and Gregory the Great, contributed to the understanding of the soul’s purification after death, prior to the General Resurrection. Curiosity in the West concerning this interim state helped give rise to later theology,[2] and by the twelfth century Purgatory had emerged as a fully developed concept,[3] achieving formal doctrinal definition at the Councils of Lyon (1245, 1274), Florence (1439), and Trent (1545-63).

The doctrine contributed greatly to Christian spirituality, ritual, piety, and imagination, giving rise to various devotions and literary works. Historically, descriptions of purgatory have emphasised the natural and supernatural bonding between the living and the dead – the belief that the souls in Purgatory were part of the church of the redeemed, and prayer for the dead, became a principal expression of the ties binding the Christian community together.[4] The teaching became "a powerful symbol of all that the holiness of God requires of man and also of His mercy and His love for men."[2]

Non-Catholic Christians have differing interpretations of the concept. Eastern Orthodox, while upholding the ancient Christian practice of prayer for the dead, generally reject the Roman Catholic understanding, as well as the penitential system to which it is tied,[5] as unwarranted innovations.[6] Protestant reformers of the 16th century came to reject the doctrine, especially because of its relationship with the granting of indulgences. In modern times, few Protestants have defended it.[6]

Purgatory as taught by the Roman Catholic Church

On an individual's death, that eternal fate of the deceased (heaven, hell, or possibly limbo) is decided at that time. Those destined for heaven but not yet pure go through purgatory. In purgatory, they suffer punishment for mortal sins whose guilt has been forgiven but whose debt of punishment has not yet been remitted. In life, one can remit such debt through penance. After death, the living can help to remit one's debt through prayer, especially the Eucharist, as well as through alms, penance, and indulgences. Guilt for venial sins might also be expiated in purgatory.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

As the full Catechism further explains, "The Church gives the name Purgatory to this final purification of the elect, which is entirely different from the punishment of the damned. The Church formulated her doctrine of faith on Purgatory especially at the Councils of Florence and Trent. The tradition of the Church, by reference to certain texts of Scripture, speaks of a cleansing fire.[7] This teaching is also based on the practice of prayer for the dead, already mentioned in Sacred Scripture: "Therefore [Judas Maccabeus] made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin" (2 Macc 12:45). From the beginning the Church has honoured the memory of the dead and offered prayers in suffrage for them, above all the Eucharistic sacrifice, so that, thus purified, they may attain the beatific vision of God. The Church also commends almsgiving, indulgences, and works of penance undertaken on behalf of the dead.[8]

Dogmatic texts about purgatory

The Council of Florence (1439) addressed purgatory, as part of its attempt to reunify the Eastern and Western churches.

- [The Council] has likewise defined, that, if those truly penitent have departed in the love of God, before they have made satisfaction by the worthy fruits of penance for sins of commission and omission, the souls of these are cleansed after death by purgatorial punishments; and so that they may be released from punishments of this kind, the suffrages of the living faithful are of advantage to them, namely, the sacrifices of Masses, prayers, and almsgiving, and other works of piety, which are customarily performed by the faithful for other faithful according to the institutions of the Church. And that the souls of those, who after the reception of baptism have incurred no stain of sin at all, and also those, who after the contraction of the stain of sin whether in their bodies, or when released from the same bodies, as we have said before, are purged, are immediately received into heaven, and see clearly the one and triune God Himself just as He is, yet according to the diversity of merits, one more perfectly than another. Moreover, the souls of those who depart in actual mortal sin or in original sin only, descend immediately into hell but to undergo punishments of different kinds.[9]

The Council of Trent (1563) addressed purgatory, in response to challenges by Protestant Reformers.

- Since the Catholic Church, instructed by the Holy Spirit, in conformity with the sacred writings and the ancient tradition of the Fathers in sacred councils, and very recently in this ecumenical Synod, has taught that there is a purgatory, and that the souls detained there are assisted by the suffrages of the faithful, and especially by the acceptable sacrifice of the altar, the holy Synod commands the bishops that they insist that the sound doctrine of purgatory, which has been transmitted by the holy Fathers and holy Councils, be believed by the faithful of Christ, be maintained, taught, and everywhere preached. Let the more difficult and subtle "questions", however, and those which do not make for "edification" [cf.1 Tim. 1:4], and from which there is very often no increase in piety, be excluded from popular discourses to uneducated people. Likewise, let them not permit uncertain matters, or those that have the appearance of falsehood, to be brought out and discussed publicly. Those matters on the contrary, which tend to a certain curiosity or superstition, or that savor of filthy lucre, let them prohibit as scandals and stumbling blocks to the faithful.[10]

This decree speaks of the existence of purgatory having already been taught by the same Council when declaring, a year earlier, that the Mass is "offered rightly according to the tradition of the apostles [can. 3], not only for the sins of the faithful living, for their punishments and other necessities, but also for the dead in Christ not yet fully purged",[11] and decreeing: "If anyone says that the sacrifice of the Mass is only one of praise and thanksgiving, or that it is a mere commemoration of the sacrifice consummated on the Cross, but not one of propitiation; or that it is of profit to him alone who receives; or that it ought not to be offered for the living and the dead, for sins, punishments, satisfactions, and other necessities: let him be anathema."[12]

Other Councils' texts, while not making dogmatic assertions, also make reference:

- First Council of Lyon (1245): In that transitory fire certainly sins, though not criminal or capital, which before have not been remitted through penance but were small and minor sins, are cleansed, and these weigh heavily even after death, if they have been forgiven in this life.[13]

- Second Council of Lyon (1274): If they die truly repentant in charity before they have made satisfaction by worthy fruits of penance for (sins) committed and omitted, their souls are cleansed after death by purgatorial or purifying punishments, as Brother John [Parastron O. F. M.] has explained to us. And to relieve punishments of this kind, the offerings of the living faithful are of advantage to these, namely, the sacrifices of Masses, prayers, alms, and other duties of piety, which have customarily been performed by the faithful for the other faithful according to the regulations of the Church (Profession of faith of Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus).[14]

Prayer and other works for souls in purgatory

Prayer for the dead

The Church's teaching on purgatory is based on the practice of prayer for the dead, a practice mentioned in pre-Christian deuterocanonical 2 Maccabees 12:46 and one that, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the Church has practiced from the beginning. In 2 Timothy 1:17–18, which is not quoted by the Catechism, Paul the Apostle, speaking of a certain Onesiphorus, says: "May the Lord grant him to find mercy from the Lord on that Day". The preceding verse is often interpreted as indicating that Onesiphorus was dead.[15]

Prayer for the dead, in the belief that the dead are thereby benefited, is part of the practice of all the ancient Christian Churches, even those that do not accept the Roman Catholic teaching on purgatory.[16] In particular, the Latin, Greek,[17] Coptic, Syrian, and Chaldaean Churches of ancient tradition offer the Eucharist on behalf of the dead.

The exhortation of Saint John Chrysostom (349– c. 407) bespeaks this practice: "Let us then give [the dead] aid and perform commemoration for them. For if the children of Job were purged by the sacrifice of their father, why do you doubt that when we too offer for the departed, some consolation arises to them? (Since God is wont to grant the petitions of those who ask for others).... Let us not then be weary in giving aid to the departed, both by offering on their behalf and obtaining prayers for them: for the common Expiation of the world is even before us. ... and it is possible from every source to gather pardon for them, from our prayers, from our gifts in their behalf, from those whose names are named with theirs. Why therefore do you grieve? Why mourn, when it is in your power to gather so much pardon for the departed?"[18]

Other good works and indulgences

In addition to prayer for the dead, it is traditional to "do good works and labours of faith and love for them."[19] Practices performed to assist them include almsgiving on their behalf and fasting and other penitential acts. To such prayers and good works, whether done for the performer's own benefit or for the good of other persons, living or dead, the Catholic Church attaches indulgences, granted from the "treasury of merits" (Christ's and the saints'), "at times remitting completely and at times partially the temporal punishment due to sin ... (urging) to perform works of piety, penitence and charity — particularly those which lead to growth in faith and which favour the common good. And if the faithful offer indulgences in suffrage for the dead, they cultivate charity in an excellent way."[20]

Temporal punishment

Souls in purgatory suffer "temporal punishment" (also called "pain of sense")[21], in contrast to "eternal punishment" (also called "pain of loss ... of the infinite good, i.e. God")[22] in hell. The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains:

- Grave sin deprives us of communion with God and therefore makes us incapable of eternal life, the privation of which is called the "eternal punishment" of sin. On the other hand every sin, even venial, entails an unhealthy attachment to creatures, which must be purified either here on earth, or after death in the state called Purgatory. This purification frees one from what is called the "temporal punishment" of sin. These two punishments must not be conceived of as a kind of vengeance inflicted by God from without, but as following from the very nature of sin. A conversion which proceeds from a fervent charity can attain the complete purification of the sinner in such a way that no punishment would remain. … While patiently bearing sufferings and trials of all kinds and, when the day comes, serenely facing death, the Christian must strive to accept this temporal punishment of sin as a grace. He should strive by works of mercy and charity, as well as by prayer and the various practices of penance, to put off completely the "old man" and to put on the "new man" (cf. Ephesians 4:24).[23]

Fire

The imagery of fire has long been common, and has links tradition to certain texts of Scripture, in particular to 1 Corinthians 3:15 and 1 Peter 1:7, which also speak of fire, whether material or metaphorical.[24] Although no dogmatic statement describes a material fire in the context of purgatory,[25] the imagery of fire has long been common in the West. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, St. Augustine stated that the pain which purgatorial fire causes is more severe than anything a man can suffer in this life, and Gregory the Great mentioned those who after this life "will expiate their faults by purgatorial flames," adding "that the pain be more intolerable than any one can suffer in this life". St. Bonaventure also stated that this punishment by fire is more severe than any punishment which comes to men in this life.[26]

The conception of the purgatorial fire as material rather than metaphorical was a cause of disagreement between Latin Christendom and the Greeks,[2] though at the Council of Florence, aimed at reconciliation between the groups, the Catholic participant Bessarion (Latin Patriarch of Constantinople) argued against the existence of real purgatorial fire, and the Greeks were assured that the Roman Church had never issued any dogmatic decree on this subject (see below). The later Council of Trent decreed: "Those matters … which tend to a certain curiosity or superstition, or that savour of filthy lucre, let them prohibit as scandals and stumbling blocks to the faithful." Recent Catholic discussions of purgatory have respected the reserve of the Council of Trent, interpreting the notion of fire in a metaphorical sense.[2]

The imagery of Purgatory involving various miseries, whether fire or more specific punishments tailored for particular vices, has a long history in Christian literature and visionary accounts. However these miseries, "like the physical horrors of the process of death itself, were evoked not to curdle the blood and oppress the spirit, but to stir the living to present action. Mortified lives of penance would make Purgatory superfluous, almsgiving and good works in time of prosperity would be better than last-minute fire insurance."[27] As explained by historian Eamon Duffy, "In the noblest, most circumstantial, and most theologically sophisticated of all medieval visions of the other world, Dante’s Commedia, Purgatory is unequivocally a place of hope and a means of ascent towards Heaven. It thus has nothing in common with Hell.[28]

Place

As with heaven[29] and hell,[30] purgatory is often spoken of as a place to which one goes or where one is.[31] But as Pope John Paul II declared when stating that "the term ('purgatory') does not indicate a place, but a condition of existence",[32] Church teaching does not endorse the idea of a place within physical space for purgatory frequently found in works of literature such as Dante Alighieri's Divina Commedia and legends such as that of St. Patrick's Purgatory.

History

Purgatory developed out of the ancient practice of prayer for the dead, and the notion that not all souls are condemned to Hell or worthy of Heaven at the moment of death. Curiosity in the West concerning the intermediate state of the soul helped give rise to later theology. St. Augustine, Gregory the Great, and others contributed to the understanding of the soul’s purification after death, prior to the General Resurrection. By the twelfth century, Purgatory had emerged as a fully developed concept.

Christian Antiquity

In Christianity, prayer for the dead, perhaps originating in ancient Jewish practice (of which the episode in 2 Maccabees 12:39–46 is a possible example),[34] is attested since at least the second century,[35] evidenced in part by the tomb inscription of Abercius, Bishop of Hierapolis in Phrygia (d. c. 200), which begs the prayers of the living.[36] Likewise, some of the inscriptions in the catacombs are in the form of prayers for those buried there.[37]

The second-century Acts of Paul and Thecla present prayer as obtaining that a dead person "be translated to a state of happiness".[39] And the third-century Passion of the Holy Martyrs Perpetua and Felicity gives expression to the belief that sins can be purged by suffering in an afterlife, and that the process can be accelerated by prayer.[2][40] Celebration of the Eucharist for the dead was also practiced, and is attested to since at least the third century.[41] When St Augustine's mother Monica was dying she told her two sons: "Lay this body anywhere, and do not let the care of it be a trouble to you at all. Only this I ask: that you will remember me at the Lord's altar, wherever you are."[42]

Many of the Church Fathers express belief in purification after death and of the communion of the living with the dead through prayer.[43] The patristic authors often understood those undergoing purification to be awaiting the Last Judgment before receiving the final blessedness of the Resurrection of the Dead, and they also often described this purification as a journey which entailed hardships but also powerful glimpses of joy.[44] Certain statements are of particular interest due to their antiquity. Irenaeus's (c. 130-202) description of the souls of the dead (awaiting the universal judgment) to be experiencing a process of purification contains the concept of purgatory.[45] Both St. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215) and his pupil, Origen (c. 185-254), developed a view of purification after death;[46] this view drew upon the notion that fire is a divine instrument from the Old Testament, and understood this in the context of New Testament teachings such as baptism by fire, from the Gospels, and a purificatory trial after death, from St. Paul.[47] For both Clement and Origen, the fire was neither a material thing nor a metaphor, but a "spiritual fire".[48] An early Latin author, Tertullian (c. 160-225), also articulated a view of purification after death.[49] In Tertullian's understanding of the afterlife, the souls of martyrs entered directly into eternal blessedness,[50] whereas the rest entered a generic realm of the dead. There the wicked suffered a foretaste of their eternal punishments,[51] whilst the good experienced various stages and places of bliss, an idea that was "universally diffused" in antiquity.[52]

Later examples, which contain further elaborations, abound.[53] Of these the most significant is St. Augustine (354-430), whose remarks concerning a purifying fire after death and the efficacy of prayer for those undergoing this purification were highly influential in later theology.[2]

Early Middle Ages

Pope Gregory the Great's Dialogues, written in the late sixth century, taught:

As for certain lesser faults, we must believe that, before the Final Judgment, there is a purifying fire. He who is truth says that whoever utters blasphemy against the Holy Spirit will be pardoned neither in this age nor in the age to come.[55] From this sentence we understand that certain offenses can be forgiven in this age, but certain others in the age to come.[56]

For Gregory, God was further illuminating the nature of the afterlife, sending visions and the like, whereby, more fully than before, the outlines of the fate of the soul immediately beyond the grave were becoming visible, like the half-light that precedes the dawn.[57] In the seventh century, the Irish abbot St. Fursa described his foretaste of the afterlife, where, though protected by angels, he was pursued by demons who said, "It is not fitting that he should enjoy the blessed life unscathed..., for every transgression that is not purged on earth must be avenged in heaven," and on his return he was engulfed in a billowing fire that threatened to burn him, "for it stretches out each one according to their merits... For just as the body burns through unlawful desire, so the soul will burn, as the lawful, due penalty for every sin."[58] The event was included by The Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiastical History, a highly popular and influential work.[59] St. Boniface also described a vision of Purgatory.[60]

Theologians of the Carolingian period, especially Alcuin, Rabanus, Haymo, and Walafrid Strabo, contributed to the development of the doctrine.[61] By the end of the tenth century, the widespread observance of All Souls' Day in the West, established in part through the influence of St. Odilo of Cluny,[62] had "helped to concentrate the imagination on the fate of departed souls and fostered a sense of solidarity between the living and the dead."[2] The great success of Cluniac monasticism helped foster a sense of spiritual fervor throughout Latin Christendom.

High Middle Ages

Amid the general elaboration of theology in the twelfth century, the studies by the masters of Paris and elsewhere concerning the theology of penance helped to fashion a notion of purgatory as a place where canonical penances unfinished in this life could be completed.[2] It was in this century that the afterlife purification acquired the name "purgatorium", from Latin purgare (to cleanse).[63] In the next century, a writing of Thomas Aquinas contains the classic formulation of the doctrine, stating that the dead in purgatory are at peace because they are sure of salvation, and that they benefit from the prayers of the living because they are still part of the Communion of Saints, from which only hell or limbo can separate one.[2]

In the High Middle Ages, purgatory also began to loom large in lay awareness, providing the rational for the immense elaboration of the cult of the intercession of the dead.[64] Many accounts of visions circulated among the laity and found their way into devotional collections. The best known examples include the Gast of Gy, the revelations of St. Brigit of Sweden,[65] and those associated with St. Patrick’s Purgatory – a popular subject of legend, written about by Henry of Sawtrey in his twelfth-century Tractatus de Purgatorio S. Patricii (and others). These accounts were designed to move the Christian to pious action on his own behalf while still in health, to complete his penances, and to be generous in charity. These were the good deeds which would accompany everyman, to plead for him, "For after death amends may no man make, For then mercy and pity doth him forsake."[66]

Building on these pictures of purgatory, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) depicted in his Purgatorio, in which purgatory is a seven-story mountain, the gradual purification of the image and likeness of God in the human soul.[67]

Medievalist Jacques Le Goff argued that purgatory was "born" in this period. Although he recognized the notion of purification after death in antiquity (specifically that Clement of Alexandria and Origen derived their view of purification from various biblical teachings), and even considered vague concepts of purifying and punishing fire to predate Christianity, Le Goff considered a radical conceptual shift to have taken place in the developed perception of purgatory from a prefatory process to a specific place.[68] In his review of Le Goff’s work, historian Alan E. Bernstein disagreed, stating that, "the insistence that there was no purgatory until it was conceived as a place represented by a noun seems unnecessarily strict."[69]

In the context of discussion with the Greeks, the two thirteenth-century Councils of Lyon considered purgatory.[2] The official teaching of the Church then and later remained limited to two elements: the existence of a state of purification for souls en route to heaven, and the efficaciousness of prayer for the dead.[70]

Certain heretics, such as Cathars and Waldensians, denied purgatory.[2]

Disputes with other Christians over purgatory

Latin-Greek relations

In the 15th century, at the Council of Florence, Eastern and Western clergymen met in an attempt to undo the Great Schism of 1054. Authorities of the Eastern Orthodox Church identified several apparent stumbling blocks to reunification, including Papal primacy, the West's unleavened bread in the Eucharist, two words in the Nicene Creed, and purgatory.[71] The Greeks objected especially to the conception of material fire and to the legalism of the Western approach, for example in the distinction between guilt and punishment.[2]

At the Council, the Catholic Latin Patriarch of Constantinople, Bessarion, argued against the existence of real purgatorial fire. The text of the Council's decree on purgatory contains no reference to fire and, without using the word "purgatorium" (purgatory), speaks only of "pains of cleansing" ("poenae purgatoriae"),[72]

Though this reunification was generally rejected in the East, certain Eastern Communities were later received into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church.[73]

Protestant objections

Protestant theologians' developing views on salvation (soteriology) excluded purgatory, in part a result from doctrinal changes concerning justification and sanctification on the part of the reformers.

For Martin Luther, justification meant "the declaring of one to be righteous", where God imputes the merits of Christ upon one who remains without inherent merit.[74] In this process, good works done in faith (i.e. through penance) are an unessential byproduct that contribute nothing to one's own state of righteousness. "Becoming perfect" came to be understood as an instantaneous act of God, so that each one of the elect (saved) experienced instantaneous glorification upon death. As such, there was little reason to pray for the dead, as there was not a process or journey of purification that continues in the afterlife. Luther wrote "We should pray for ourselves and for all other people, even for our enemies, but not for the souls of the dead." (expanded Small Catechism, Question No. 211) Luther stopped believing in purgatory around 1530,[75] and later openly affirmed the doctrine of soul sleep,[76] although subsequent Lutheran confessions do not expressly reject all ideas of purification after death.[2]

Purgatory came to be seen as one of the "unbiblical corruptions" that had entered Church teachings sometime subsequent to the apostolic age. The Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England, produced during the English Reformation, stated: "The Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory...is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture; but rather repugnant to the word of God" (article 22). John Calvin, central theologian of Reformed Protestantism, considered purgatory a superstition, writing in his Institutes (5.10): "The doctrine of purgatory ancient, but refuted by a more ancient Apostle. Not supported by ancient writers, by Scripture, or solid argument. Introduced by custom and a zeal not duly regulated by the word of God… we must hold by the word of God, which rejects this fiction."

Counter-Reformation and thereafter

An early reply to the Reformers was made by St. John Fisher, who based his defence of the doctrine on the writings of the Church Fathers, and the practice of prayer for the dead from the earliest times.[2]

The Council of Trent gave the official response of the Catholic Church to the critics, repeating the teaching already given by the First Council of Lyon. The text of its decree (given above) restates the concepts of purification after death and the efficacy of prayers for the dead, and sternly instructed preachers not to push beyond that and distract, confuse, and mislead the faithful with unnecessary speculations concerning the nature and duration of purgatorial punishments. The legends and speculation that had grown up and still continue to grow up around the concept of purgatory were not treated as Church teaching. The Council decreed: "Those matters … which tend to a certain curiosity or superstition, or that savour of filthy lucre, let them prohibit as scandals and stumbling blocks to the faithful." Recent Catholic discussions of purgatory have respected the reserve of the Council of Trent, interpreting the notion of fire in a metaphorical sense, and the temporal aspect in terms of intensity.[2]

Some Protestants have accepted prayer for the dead, an intermediate state of purification, and even the term "purgatory". William Forbes, the first Scottish Episcopal Bishop of Edinburgh, affirmed prayer for the dead and described an intermediate state where the soul is purified by its fervent longing for God.[2]Anglican apologist C. S. Lewis believed in purgatory, if not in what the Reformers called "the Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory", and defended the notion.[77] Other Anglicans, in particular Anglo-Catholics (such as the Guild of All Souls), profess belief in purgatory.

Later ideas about purgatory

Questions already discussed among theologians since the Middle Ages continued to be developed. One is whether the souls in purgatory can pray for the living. When considering whether the saints in heaven pray for us,[78] Saint Thomas Aquinas said that the souls in purgatory cannot. According to the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Saint Robert Bellarmine (1542 – 1621) advocated petitioning the souls in purgatory to pray for one,[2] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, on the contrary, Saint Robert Bellarmine (in De Purgatorio, lib. II, xv), while finding unconvincing the reason given by Saint Thomas Aquinas, said that, ordinarily speaking, it is superfluous to invoke the prayers of those in purgatory, "for they are ignorant of our circumstances and condition." The Catholic Encyclopedia attributes instead to the theologian Francisco Suárez (in De poenit., disp. xlvii, s. 2, n. 9) the opinion "that the souls in purgatory are holy, are dear to God, love us with a true love and are mindful of our wants; that they know in a general way our necessities and our dangers, and how great is our need of divine help and divine grace".

Related beliefs continued to grow, such as the Sabbatine privilege, which appeared in the second half of the fifteenth century, the wondrous powers for releasing souls from purgatory of a prayer of uncertain date attributed to Gertrude the Great. There were accounts too of souls in purgatory passing "their purification in the air, or by their graves, or near altars where the Blessed Sacrament is, or in the rooms of those who pray for them, or amid the scenes of their former vanity and frivolity".[79]

Purgatory themes have also been prominent in various works of literature, such as Shakespeare's Hamlet (1603), Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol, and the European ghost-story tradition in general.[80]

Footnotes

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church,1030-1031 (section entitled, "The Final Purification, or Purgatory); cf. Saint Peter Catholic Church

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 Cite error: The named reference "Oxford" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Jo Ann H. Moran Cruz and Richard Gerberding, Medieval Worlds: An Introduction to European History 300-1492 (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004), p. 9.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), p349.

- ^ The ancient Christian Churches have a system of canonical discipline whereby an act of penance, called epitimia in Greek, is imposed for sins confessed (The Canonical Tradition of the Orthodox Church; Catechism of Philaret, 356). The practice of indulgences arose from that of granting reductions of these imposed acts of penance (The Historical Origin of Indulgences).

- ^ a b purgatory. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 31, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-260350

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1030-1031 (section entitled, "The Final Purification, or Purgatory); cf. Council of Florence (1439): DS 1304; Council of Trent (1563): DS 1820; (1547): 1580; see also Benedict XII, Benedictus Deus (1336): DS 1000.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1032; cf. Council of Trent 6.30, 22.2-3.

- ^ Denzinger 1304-1306 (old numbering, 693)

- ^ Denzinger 1820 (old numbering, 983)

- ^ Denzinger 1743 (old numbering, 940

- ^ Denzinger 1753 (old numbering, 950)

- ^ Denzinger 838 (old numbering, 456)

- ^ Denzinger 856 (old numbering, 464)

- ^ "Paul speaks of Onesiphorus in a way that seems obviously to imply that the latter was already dead: 'The Lord give mercy to the house of Onesiphorus' - as to a family in need of consolation" (Catholic Encyclopedia: Prayers for the Dead. Protestant commentators either deny the validity of the inference that Onesiphorus was dead or say that the expression Paul uses is not a prayer but "a pious wish" (The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia).

- ^ Why do we pray for the deceased? (Armenian Apostolic Church); Honoring the Ancestors (Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria); Catechism of St. Philaret of Moscow, 376] (Eastern Orthodox Church); East Syrian Rite (Assyrian Church of the East)

- ^ Constas H. Demetry, Catechism of the Eastern Orthodox Church p. 37; Orthodox Catechism of Philaret, 376

- ^ Homily 41 on 1 Corinthians, 8

- ^ Akathist for those who have fallen asleep

- ^ Apostolic Constitution Indulgentiarum Doctrina, 8

- ^ [http://www.newadvent.org/summa/2087.htm#4 Summa Theologica, I-II, q. 87, a. 4

- ^ Ibidem

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1472-1473

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1031

- ^ Cf. "Dogmatic texts about Purgatory" above

- ^ [1]

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992). p. 343.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992). p. 343.

- ^ Heaven is spoken of as a place where God's throne is established, "where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God"(Colossians 3:1), etc.

- ^ Is there an actual place called "Hell"?; The Place of Hell]; The Truth about Hell; The Place and Life of Hell

- ^ "Purgatory ... is usually thought of as having some position in space, and as being distinct from heaven and hell; but any theory as to its exact latitude and longitude, such as underlies Dante's description, must be regarded as imaginative" ([http://encyclopedia.jrank.org/PRE_PYR/PURGATORY_Late_Lat_purgatorium_.html 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica: Purgatory).

- ^ Audience of 4 August 1999

- ^ Cabrol and Leclercq, Monumenta Ecclesiæ Liturgica. Volume I: Reliquiæ Liturgicæ Vetustissimæ (Paris, 1900-2) pp. ci-cvi, cxxxix.

- ^ George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106

- ^ Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106; cf. Pastor I, iii. 7, also Ambrose, De Excessu fratris Satyri 80

- ^ Gerald O' Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 217

- ^ Cabrol and Leclercq, Monumenta Ecclesiæ Liturgica. Volume I: Reliquiæ Liturgicæ Vetustissimæ (Paris, 1900-2) pp. ci-cvi, cxxxix.

- ^ Augustine, De Civitate Dei, 21. 24, etc.

- ^ Acts of Paul and Thecla, 8:5-7

- ^ The Passion of the Holy Martyrs Perpetua and Felicity, 2:3-4; "At St. Augustine's time, the Acts were still held in such esteem that he has to warn his listeners not to put them on a level with the canonical Scriptures (De anima et eius origine I, 10, 12)" – ([http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/actsperpetua.html J. Quasten: Patrology, vol. 1, p. 181).

- ^ Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106

- ^ Confessions, Book Six, Chapter XI

- ^ Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27.

- ^ Anthony Dragani, From East to West

- ^ Christian Dogmatics vol. 2 (Philadelphia : Fortress Press, 1984) p. 503; cf. Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.31.2, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers eds. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979) 1:560 cf. 5.36.2 / 1:567; cf. George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 107

- ^ Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; cf. Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London, Williams & Norgate, 1995) p. 337; Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 6:14

- ^ Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) p. 53; cf. Leviticus 10:1–2, Deuteronomy 32:22, 1Corinthians 3:10–15; Origen, in arguing against soul sleep, stated that the souls of the elect immediately entered paradise unless not yet purified, in which case they passed into a state of punishment, a penal fire, which is to be conceived as a place of purification — see Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London: Williams & Norgate, 1905) p. 377. read online.

- ^ Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) pp. 55-57; cf. Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 7:6 and 5:14

- ^ Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; cf. Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London, Williams & Norgate, 1995) p. 296 n. 1; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912); Tertullian De Anima

- ^ A. J. Visser, "A Bird's-Eye View of Ancient Christian Eschatology", in Numen (1967) p. 13

- ^ A. J. Visser, "A Bird's-Eye View of Ancient Christian Eschatology", in Numen (1967) p. 13

- ^ Adolf von Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London: Williams & Norgate, 1905) p. 296 n. 1. read online

- ^ For example, St. Cyprian (d. 258), Letters 51:20; also St. John Chrysostom (c. 347-407), Homily on First Corinthians 41:5, and his Homily on Philippians 3:9-10. See Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; and Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36.

- ^ Vita Gregorii, ed. B. Colgrave, chapter 26 (see also Colgrave's introduction p. 51); John the Deacon, Life of Saint Gregory, IV, 70.

- ^ Matthew 12:32

- ^ Gregory the Great, Dialogues 4, 39: PL 77, 396; cf. Matthew 12:31

- ^ Peter Brown, Rise of Western Christendom" (Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 2003) p. 258; cf. Gregory the Great, Dialogues 4.42.3

- ^ Brown, Rise of Western Christendom (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003) p. 259; cf. Vision of Fursa 8.16, 16.5

- ^ Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica 3.19

- ^ George Cross, "The Medieval Catholic Doctrine of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 192

- ^ George Cross, "The Medieval Catholic Doctrine of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 192

- ^ Observance of the feast existed earlier in local forms: in the sixth century, Benedictine monasteries commemorated the deceased members at Whitsuntide, and, in the next century, there was in Spain a similar celebration on another day; see the Catholic Encyclopedia. The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates several All Souls' Days in the year.

- ^ C. S. Watkins, "Sin, penance and purgatory in the Anglo-Norman realm: the evidence of visions and ghost stories", in Past and Present 175 (May 2002) pp. 3-33.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 339.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), p338.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), p342; quoted passage is from G. A. Lester, Three Late Medieval Morality Plays, p. 102, lines 912-13.

- ^ purgatory. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 1, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-260349

- ^ Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984)

- ^ Alan E. Bernstein, "Review of La naissance du purgatoire", in "Speculum" (1984), p. 181.

- ^ Cf. From East to West

- ^ The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999) p. 201; cf. Orthodoxinfo.com, The Orthodox Response to the Latin Doctrine of Purgatory

- ^ Denzinger 1304 (old numbering, 693)

- ^ The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999) p. 202

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 119

- ^ +Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 580; cf. Koslofsky, Reformation of the Dead pp. 34-39

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) pp. 580-581; cf. Koslofsky, Reformation of the Dead p. 48

- ^ While saying that "the Reformers had good reasons for throwing doubt on the 'Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory' as that Romish doctrine had then become", Lewis stated: "I believe in Purgatory … Our souls demand Purgatory, don't they? Would it not break the heart if God said to us, 'It is true, my son, that your breath smells and your rags drip with mud and slime, but we are charitable here and no one will upbraid you with these things, nor draw away from you. Enter into the joy'? Should we not reply, 'With submission, sir, and if there is no objection, I'd rather be cleaned first.' 'It may hurt, you know' – 'Even so, sir.' I assume that the process of purification will normally involve suffering. Partly from tradition; partly because most real good that has been done me in this life has involved it. But I don't think the suffering is the purpose of the purgation."Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, chapter 20. Extracts may be read at Angelfire and café theology.

- ^ Summa Theologica II-II:83:11

- ^ Opus Sanctorum Angelorum

- ^ purgatory. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 1, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-260349

See also

|

External links

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1030-1032

- CatholicBridge.com, Purgatory — Ecumenical article by David MacDonald concerning Evangelical and Catholic belief

- Catholic Answers, Purgatory — Catholic apologetic article

- NewAdvent.org, Purgatory — 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article

- bringyou.to/apologetics — Readings from the Church Fathers and other sources on Purgatory, by Phil Porvaznik

- EWTN.com library, Heaven, Hell and Purgatory according to Pope John Paul II — Articles from the newspaper of the Holy See, L'Osservatore Romano, July-August 1999

- JewishEncyclopedia.com, Purgatory — Article by Kaufmann Kohler in the online Jewish Encyclopedia

- New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Purgatory — Article by C. A. Beckwith in the 19th century Protestant encyclopedia (ed. Philip Schaff)

- Purgatory account in the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Purgatory article in Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

- I Believe in Purgatory... — excerpt from C. S. Lewis's Letters To Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, chapter 20

- Frequently Asked Questions at Holy Souls Online

- Purgatory and praying for the dead on Catholic Apologetic

- "Prisoner of the King: Thoughts on the Catholic Doctrine of Purgatory", H. J. Coleridge, 1889. retrieved 24 May 2007

- Three Purgatory Poems, a scholarly history of Purgatory from Medieval Institute Publications