Purgatory

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Purgatory is a state, process, or place of purification or punishment in which, according medieval Christian and Roman Catholic beliefs, the dead are "purified" or "cleansed" prior to entering Heaven. [1][2]

According to Roman Catholicism beliefs, some sins are so severe that in the afterlife, they eternally separate one from God-- a condition called Hell. But lesser states of sin are not severe enough to prevent one eventually attaining eternal union with God-- a condition called Heaven. Souls who die in this lesser state of sin will will ultimately be united with God, but first they must be "purified" of "cleansed"-- a condition called Purgatory.

Roman Catholics believe that the acts of the living, such as prayer and sacrifice, can have positive effects on the dead who are in Purgatory. Historically, Purgatory was often envisioned as a physical place of fiery punishment, although modern Catholic theologians tend to reject this interpretation.

The doctrine of Purgatory was first explicitly formulated in the 12th century, but many elements of the doctrine are more ancient. For example, two elements which predate the 12th century are the the belief that prayer for the dead is valuable and the notion that not all souls are condemned to Hell or worthy of Heaven at the moment of death.[3]

Among other Christian denominations, the concept of Purgatory is controversial. The Eastern Orthodox Church generally rejects the Roman Catholic understanding of Purgatory, although they do practice prayer for the dead.[3][4]. Protestants, with few exceptions, do not believe in a process of purification after death.[5]. Leaders of the Protestant Reformation particularly objected to the medieval Roman Catholic church's practice of granting "indulgences"-- a pardoning of the sins of souls in Purgatory-- in exchange for monetary donations to the Church.[6]

Overview

Purgatory is a "place or condition" in the Latin Rite, which is the dominant particular Church of the Roman Catholic Church, to which about 98% of Roman Catholics belong.

Heaven and Hell

Immediately after death, a person undergoes judgment in which the soul's eternal destiny is specified. Souls which are entirely free from sin are eternally united with God in what is called Heaven, often envisioned seen as a paradise of eternal joy. Other persons, who have "sinned gravely" [7] enter Hell, a state of eternal separation from God often envisioned as fiery place of punishment.[8]

Purgatory's role

Roman Catholicism, however, accepts the possibility of a third option. Roman Catholic doctrine envisions the possibility that a soul might not be so filled with mortal sins as to immediately descend into Hell, but at the same time, might not be sufficiently free from sin to immediate ascend into Heaven. Such souls, ultimately destined to be united with God in Heaven, first entering into Purgatory-- a state of purification. In Purgatory, souls "achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven."[9]

Sin

Roman Catholics make a distinction between two different types of sin. [10] Mortal sin is a "grave violation of God's law" that "destroys" a person's love for God.[11] Unless redeemed by repentance, a mortal sin causes "exclusion from Christ's kingdom" resulting in "the eternal death of hell".[12]

In contrast, a venial sin (meaning "forgivable" sin) is a lesser sin, which "does not break the covenant with God". [13] A venial sin, although still "constituting a moral disorder", does not deprive the sinner of the "eternal happiness" of Heaven.

According to Roman Catholicism, the pardon and purification of sin can occur during life-- for example, in the Sacrament of Baptism and the Sacrament of Penance. However, if this purification is not achieved in life, venial sins can still be purified after death. The specific name given to this purification of sin after death is "Purgatory".

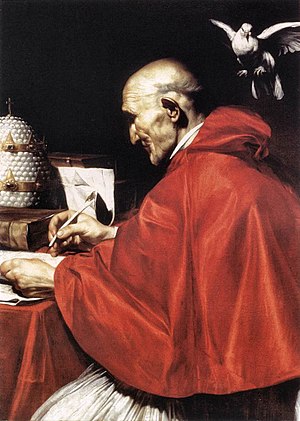

Pain and Fire

Purgatory has long been associated with the image of painful punishment and fire. Historically, Purgatory was viewed as a place of painful, tormenting fire, not unlike that found in descriptions of Hell. St. Augustine described the fires as more painful than anything a man can suffer in this life. Pope Gregory I similarly mentioned "purgatorial flames," adding "that the pain be more intolerable than any one can suffer in this life". St. Bonaventure also stated that this punishment by fire is more severe than any punishment which comes to men in this life.[14]

Modernly, the Roman Catholic church have tended to view purgatorial fire as more metaphorical fire rather than a literal one, or as more of a "cleansing fire" rather than "painful fire". The Catechism of the Catholic Church discussion of Purgatory speaks of a "cleansing fire" and a "purifying fire", but does not make any explicit mention of a "painful" fire. On the subject of the punishment of sin, the modern Catechism says that such punishment "must not be conceived of as a kind of vengeance inflicted by God from without, but as following from the very nature of sin."

The existence or absence of punishing fire is one source of contention between the Western Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church (see below).

Prayer for the dead and Indulgences

The Roman Catholic Church teaches that the fate of those in Purgatory can be affected by the actions of the living. According to this belief, the living are encouraged to engage in prayer and sacrifice for the dead, in the hope that such prayers will be have a positive impact on those in Purgatory. Acts of sacrifice such charitable donations, fasting, and other penitential act are similarly believed to aid those in Purgatory.

A related concept is the practice of indulgences. An indulgence is a remission of the punishment which would normally accompany sins that have been forgiven. Indulgences are issues by the Pope or those members of the clergy designated by the Pope to issue indulges. Indulgences may be obtained for oneself, or on behalf of specific deceased individuals.

Traditionally, prayers for the dead and indulgences were sometimes envisioned as decreasing the "duration" of time the dead would spend in Purgatory. For example, prior to the 1960s, some indulgences were measured in term of days, weeks, months, or years-- leading to the misconception that indulgences remit a specific period of time equal to the length of the soul's stay in Purgatory. Technically, however, the stated length of time actually indicated that the indulgence was equal to the amount of remission the individual would have earned by performing a canonical penance for that period of time. For example, the amount of punishment remitted by a “forty day” indulgence would be equal to the amount of punishment remitted by the individual performing forty days of penance. Modernly, Roman Catholic theologians whether a physical concept such "duration" can rationally be applied to souls in Purgatory.

The practice of granting indulgences was a source of controversy which results in the Protestant Reformation. The 16th century Roman Catholic Church had a practice of indulgences in exchange for monetary donations-- an policy which was seen by Martin Luther as the purchase and sale of salvation. In his 95 Theses, Luther specifically objected to a "marketing slogan" of sorts which was used by the Church to encourage the purchase of indulgences: "As soon as a coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs".[15]

Purgatory as a physical place

In antiquity, both Heaven and Hell were regarded as physical places existing within the physical universe. Heaven for example, was traditionally believed to be associated with the sky, and to exist "above". Hell as often believed to be "below", located within the center of the Earth. Similarly, Purgatory was sometimes considered to be a physical place located within space. For example, in Dante's 14th century work The Divine Comedy, Purgatory is depicted as a mountain in the southern hemisphere.

Modernly, practically all religions reject the notion of Heaven, Hell, or Purgatory being physical locations. The Roman Catholic Church has explicitly denounced the concept of Purgatory as a "place"-- for example, in 1999, Pope John Paul II declared "the term ('purgatory') does not indicate a place, but a condition of existence".[16] Authoritative church teachings similarly dismiss the concept of Purgatory as a place within physical space.

Purgatory in the authoritative teachings of the contemporary Roman Catholic Church

Like nearly all religions, Roman Catholic Church does not regard any and all writings or teachings produced by its members to be authoritative. Instead, only a small fraction of the beliefs, teachings, and doctrines proposed by Catholics are ever considered to authoritative. For example, Dante's work The Divine Comedy, although a highly influential catholic work, is not considered to be an authoritative factual exposition of the Roman Catholic afterlife.

Purgatory in The Catechism of the Catholic Church

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, published in 1997, is the official exposition of the teachings of the modern Roman Catholic Church The section on Purgatory[17] reads:

- THE FINAL PURIFICATION, OR PURGATORY

- All who die in God's grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven.

- The Church gives the name Purgatory to this final purification of the elect, which is entirely different from the punishment of the damned.(Cf. Council of Florence (1439): DS 1304; Council of Trent (1563): DS 1820; (1547): 1580; see also Benedict XII, Benedictus Deus (1336): DS 1000.) The Church formulated her doctrine of faith on Purgatory especially at the [15th century] Councils of Florence and [the 16th century] Trent . The tradition of the Church, by reference to certain texts of Scripture, speaks of a cleansing fire:(Cf. 1 Cor 3:15, 1 Pet 1:7)

- As for certain lesser faults, we must believe that, before the Final Judgment, there is a purifying fire. He who is truth says that whoever utters blasphemy against the Holy Spirit will be pardoned neither in this age nor in the age to come. From this sentence we understand that certain offenses can be forgiven in this age, but certain others in the age to come.(St. Gregory the Great, Dial. 4, 39: PL 77, 396; cf. ⇒ Mt 12:31.)

- This teaching is also based on the practice of prayer for the dead, already mentioned in Sacred Scripture: "Therefore [Judas Maccabeus] made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin." (2 Macc 12:46.) From the beginning the Church has honored the memory of the dead and offered prayers in suffrage for them, above all the Eucharistic sacrifice, so that, thus purified, they may attain the beatific vision of God.(Cf. Council of Lyons II (1274): DS 856.) The Church also commends almsgiving, indulgences, and works of penance undertaken on behalf of the dead:

- Let us help and commemorate them. If Job's sons were purified by their father's sacrifice, why would we doubt that our offerings for the dead bring them some consolation? Let us not hesitate to help those who have died and to offer our prayers for them.(St. John Chrysostom, Hom. in 1 Cor. 41, 5: PG 61, 361; cf. ⇒ Job 1:5.)

The section on Indulgences also mentions Purgatory: [18]

- THE PUNISHMENT OF SIN

- To understand this doctrine and practice of the Church, it is necessary to understand that sin has a double consequence. Grave sin deprives us of communion with God and therefore makes us incapable of eternal life, the privation of which is called the "eternal punishment" of sin. On the other hand every sin, even venial, entails an unhealthy attachment to creatures, which must be purified either here on earth, or after death in the state called Purgatory. This purification frees one from what is called the "temporal punishment" of sin. These two punishments must not be conceived of as a kind of vengeance inflicted by God from without, but as following from the very nature of sin. A conversion which proceeds from a fervent charity can attain the complete purification of the sinner in such a way that no punishment would remain

Purgatory in the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church

The Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, first published in 2005, is a more concise version of the Catechism which presents information in the form of a dialog. The work discusses Purgatory thusly:[19]

What is purgatory?

- Purgatory is the state of those who die in God’s friendship, assured of their eternal salvation, but who still have need of purification to enter into the happiness of heaven.

How can we help the souls being purified in purgatory?

- Because of the communion of saints, the faithful who are still pilgrims on earth are able to help the souls in purgatory by offering prayers in suffrage for them, especially the Eucharistic sacrifice. They also help them by almsgiving, indulgences, and works of penance.

Purgatory and other rites, denominations, and religions

Purgatory is strongly associated with the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church, but other rites, denominations, and religious do have views on the concept of Purgatory.

Purgatory and the Eastern Catholic Churches

The Roman Catholic Church is made up of 23 distinct Churches. The Latin Church is by far the most populous and influential-- its members make up approximately 98% of Roman Catholic Church. The remaining 22 churches are known collectively as the Eastern Catholic Churches. Historically, most of the Eastern Catholic Churches were, at some point in history, separate entities that later united with the Latin Church.

The Eastern Catholic Churches are full and equal members of the Roman Catholic Church, are under the leadership of the Pope, and officially accept all the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church (including those involving Purgatory). However, there are also differences between the the Eastern Catholic Churchs and the Latin Church in numerous matters of ceremony, tradition, and terminology. For example, while the priests in the Latin Church take vows of celibacy, married men are eligible to join the priesthood in most Eastern Catholic Churches.

One of the differences between the Latin Church and the Eastern Catholic Churches concerns the views about Purgatory. Many of Eastern Catholic Churches do not, in general, use the word "Purgatory", but they do agree that there is a "final purification" for souls destined for Heaven, and that prayers can help the dead who are in that state of "final purification". In general, neither the members of the Latin Church nor the members of the Easter Catholic Churches regard these differences as major points of active dispute, but instead see the differences more as minor nuances and differences of tradition. For example, a treaty which formalized the admission of Eastern Catholic Churches into the Roman Catholic Church explicitly states, "We shall not debate about purgatory," implying that both sides could "agree to disagree" on the precise details of the final purification".[20]

Eastern Orthodox views of Purgatory

Eastern Orthodox Christians generally reject the Roman Catholic understanding of Purgatory. [3] According to Eastern Orthodox beliefs, after death, a soul is either sent to heaven or hell, following the Temporary Judgment occurring immediately after death. Eastern Orthodox theology does not generally describe the process of purification after death as involving suffering or fire, although it is nevertheless describes it as a "direful condition". [21] Eastern Orthodox Christians do, however, practice prayer for the dead, and they accept that those prayers can affect the state of the deceased souls.

Protestant views of Purgatory

In general, Protestant churches do not accept the doctrine of Purgatory. One of Protestantism's central tenets is Sola scriptura, a Latin phrase which translates to "Scripture alone". Protestants believe that the Bible alone is the basis for valid Christian Doctrine and, since the Protestant Bible contains no overt, explicit discussion of Purgatory, Protestants reject it as an "unbiblical" belief.

Another tenet of Protestantism is Sola fide-- "By faith alone". While Catholicism regards both good works and faith as being essential to salvation, Protestants believe faith alone is sufficient to achieve salvation and that good works are merely evidence of that faith. Salvation is generally seen as discrete event which takes place during one's lifetime. Instead of distinguishing between mortal and venial sins, Protestants believe that one's faith or state of "salvation" dictates one's place in the afterlife. Those who have been "saved" by God are destined for heaven, while those have not been saved will be excluded from Heaven. Accordingly, they reject the notion of any "third state" or "third place" such as Purgatory.

History

Purgatory developed out of the ancient practice of prayer for the dead, and the notion that not all souls are condemned to Hell or worthy of Heaven at the moment of death. Curiosity in the West concerning the intermediate state of the soul helped give rise to later theology. St. Augustine, Gregory the Great, and others contributed to the understanding of the soul’s purification after death, prior to the General Resurrection. By the twelfth century, Purgatory had emerged as a fully developed concept.

Christian Antiquity

In Christianity, prayer for the dead, perhaps originating in ancient Jewish practice (of which the episode in 2 Maccabees 12:39–46 is a possible example),[23] is attested since at least the second century,[24] evidenced in part by the tomb inscription of Abercius, Bishop of Hierapolis in Phrygia (d. c. 200), which begs the prayers of the living.[25] Likewise, some of the inscriptions in the catacombs are in the form of prayers for those buried there.[26]

The second-century Acts of Paul and Thecla present prayer as obtaining that a dead person "be translated to a state of happiness".[28] And the third-century Passion of the Holy Martyrs Perpetua and Felicity gives expression to the belief that sins can be purged by suffering in an afterlife, and that the process can be accelerated by prayer.[3][29] Celebration of the Eucharist for the dead was also practiced, and is attested to since at least the third century.[30] When St Augustine's mother Monica was dying she told her two sons: "Lay this body anywhere, and do not let the care of it be a trouble to you at all. Only this I ask: that you will remember me at the Lord's altar, wherever you are."[31]

Many of the Church Fathers express belief in purification after death and of the communion of the living with the dead through prayer.[32] The patristic authors often understood those undergoing purification to be awaiting the Last Judgment before receiving the final blessedness of the Resurrection of the Dead, and they also often described this purification as a journey which entailed hardships but also powerful glimpses of joy.[33] Certain statements are of particular interest due to their antiquity. Irenaeus's (c. 130-202) description of the souls of the dead (awaiting the universal judgment) to be experiencing a process of purification contains the concept of purgatory.[34] Both St. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215) and his pupil, Origen (c. 185-254), developed a view of purification after death;[35] this view drew upon the notion that fire is a divine instrument from the Old Testament, and understood this in the context of New Testament teachings such as baptism by fire, from the Gospels, and a purificatory trial after death, from St. Paul.[36] For both Clement and Origen, the fire was neither a material thing nor a metaphor, but a "spiritual fire".[37] An early Latin author, Tertullian (c. 160-225), also articulated a view of purification after death.[38] In Tertullian's understanding of the afterlife, the souls of martyrs entered directly into eternal blessedness,[39] whereas the rest entered a generic realm of the dead. There the wicked suffered a foretaste of their eternal punishments,[40] whilst the good experienced various stages and places of bliss, an idea that was "universally diffused" in antiquity.[41]

Later examples, which contain further elaborations, abound.[42] Of these the most significant is St. Augustine (354-430), whose remarks concerning a purifying fire after death and the efficacy of prayer for those undergoing this purification were highly influential in later theology.[3]

Early Middle Ages

Pope Gregory the Great's Dialogues, written in the late sixth century, taught:

As for certain lesser faults, we must believe that, before the Final Judgment, there is a purifying fire. He who is truth says that whoever utters blasphemy against the Holy Spirit will be pardoned neither in this age nor in the age to come.[44] From this sentence we understand that certain offenses can be forgiven in this age, but certain others in the age to come.[45]

For Gregory, God was further illuminating the nature of the afterlife, sending visions and the like, whereby, more fully than before, the outlines of the fate of the soul immediately beyond the grave were becoming visible, like the half-light that precedes the dawn.[46] In the seventh century, the Irish abbot St. Fursa described his foretaste of the afterlife, where, though protected by angels, he was pursued by demons who said, "It is not fitting that he should enjoy the blessed life unscathed..., for every transgression that is not purged on earth must be avenged in heaven," and on his return he was engulfed in a billowing fire that threatened to burn him, "for it stretches out each one according to their merits... For just as the body burns through unlawful desire, so the soul will burn, as the lawful, due penalty for every sin."[47] The event was included by The Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiastical History, a highly popular and influential work.[48] St. Boniface also described a vision of Purgatory.[49]

Theologians of the Carolingian period, especially Alcuin, Rabanus, Haymo, and Walafrid Strabo, contributed to the development of the doctrine.[50] By the end of the tenth century, the widespread observance of All Souls' Day in the West, established in part through the influence of St. Odilo of Cluny,[51] had "helped to concentrate the imagination on the fate of departed souls and fostered a sense of solidarity between the living and the dead."[3] The great success of Cluniac monasticism helped foster a sense of spiritual fervor throughout Latin Christendom.

High Middle Ages

Amid the general elaboration of theology in the twelfth century, the studies by the masters of Paris and elsewhere concerning the theology of penance helped to fashion a notion of purgatory as a place where canonical penances unfinished in this life could be completed.[3] It was in this century that the afterlife purification acquired the name "purgatorium", from Latin purgare (to cleanse).[52] In the next century, a writing of Thomas Aquinas contains the classic formulation of the doctrine, stating that the dead in purgatory are at peace because they are sure of salvation, and that they benefit from the prayers of the living because they are still part of the Communion of Saints, from which only hell or limbo can separate one.[3]

In the High Middle Ages, purgatory also began to loom large in lay awareness, providing the rational for the immense elaboration of the cult of the intercession of the dead.[53] Many accounts of visions circulated among the laity and found their way into devotional collections. The best known examples include the Gast of Gy, the revelations of St. Brigit of Sweden,[54] and those associated with St. Patrick’s Purgatory – a popular subject of legend, written about by Henry of Sawtrey in his twelfth-century Tractatus de Purgatorio S. Patricii (and others). These accounts were designed to move the Christian to pious action on his own behalf while still in health, to complete his penances, and to be generous in charity. These were the good deeds which would accompany everyman, to plead for him, "For after death amends may no man make, For then mercy and pity doth him forsake."[55]

Building on these pictures of purgatory, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) depicted in his Purgatorio, in which purgatory is a seven-story mountain, the gradual purification of the image and likeness of God in the human soul.[56]

Medievalist Jacques Le Goff argued that purgatory was "born" in this period. Although he recognized the notion of purification after death in antiquity (specifically that Clement of Alexandria and Origen derived their view of purification from various biblical teachings), and even considered vague concepts of purifying and punishing fire to predate Christianity, Le Goff considered a radical conceptual shift to have taken place in the developed perception of purgatory from a prefatory process to a specific place.[57] In his review of Le Goff’s work, historian Alan E. Bernstein disagreed, stating that, "the insistence that there was no purgatory until it was conceived as a place represented by a noun seems unnecessarily strict."[58]

In the context of discussion with the Greeks, the two thirteenth-century Councils of Lyon considered purgatory.[3] The official teaching of the Church then and later remained limited to two elements: the existence of a state of purification for souls en route to heaven, and the efficaciousness of prayer for the dead.[59]

Certain heretics, such as Cathars and Waldensians, denied purgatory.[3]

Latin-Greek Relations during the Middle Ages

In the 15th century, at the Council of Florence, Eastern and Western clergymen met in an attempt to undo the Great Schism of 1054. Authorities of the Eastern Orthodox Church identified several apparent stumbling blocks to reunification, including Papal primacy, the West's unleavened bread in the Eucharist, two words in the Nicene Creed, and purgatory.[60] The Greeks objected especially to the conception of material fire and to the legalism of the Western approach, for example in the distinction between guilt and punishment.[3]

At the Council, the Catholic Latin Patriarch of Constantinople, Bessarion, argued against the existence of real purgatorial fire. The text of the Council's decree on purgatory contains no reference to fire and, without using the word "purgatorium" (purgatory), speaks only of "pains of cleansing" ("poenae purgatoriae"),[61]

Though this reunification was generally rejected in the East, certain Eastern Communities were later received into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church.[62]

The Reformation

Protestant theologians' developing views on salvation (soteriology) excluded purgatory, in part a result from doctrinal changes concerning justification and sanctification on the part of the reformers.

For Martin Luther, justification meant "the declaring of one to be righteous", where God imputes the merits of Christ upon one who remains without inherent merit.[63] In this process, good works done in faith (i.e. through penance) are an unessential byproduct that contribute nothing to one's own state of righteousness. "Becoming perfect" came to be understood as an instantaneous act of God, so that each one of the elect (saved) experienced instantaneous glorification upon death. As such, there was little reason to pray for the dead, as there was not a process or journey of purification that continues in the afterlife. Luther wrote "We should pray for ourselves and for all other people, even for our enemies, but not for the souls of the dead." (expanded Small Catechism, Question No. 211) Luther stopped believing in purgatory around 1530,[64] and later openly affirmed the doctrine of soul sleep,[65] although subsequent Lutheran confessions do not expressly reject all ideas of purification after death.[3]

Purgatory came to be seen as one of the "unbiblical corruptions" that had entered Church teachings sometime subsequent to the apostolic age. The Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England, produced during the English Reformation, stated: "The Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory...is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture; but rather repugnant to the word of God" (article 22). John Calvin, central theologian of Reformed Protestantism, considered purgatory a superstition, writing in his Institutes (5.10): "The doctrine of purgatory ancient, but refuted by a more ancient Apostle. Not supported by ancient writers, by Scripture, or solid argument. Introduced by custom and a zeal not duly regulated by the word of God… we must hold by the word of God, which rejects this fiction."

Counter-Reformation and thereafter

An early reply to the Reformers was made by St. John Fisher, who based his defence of the doctrine on the writings of the Church Fathers, and the practice of prayer for the dead from the earliest times.[3]

The Council of Trent gave the official response of the Catholic Church to the critics, repeating the teaching already given by the First Council of Lyon. The text of its decree (given above) restates the concepts of purification after death and the efficacy of prayers for the dead, and sternly instructed preachers not to push beyond that and distract, confuse, and mislead the faithful with unnecessary speculations concerning the nature and duration of purgatorial punishments. The legends and speculation that had grown up and still continue to grow up around the concept of purgatory were not treated as Church teaching. The Council decreed: "Those matters … which tend to a certain curiosity or superstition, or that savour of filthy lucre, let them prohibit as scandals and stumbling blocks to the faithful." Recent Catholic discussions of purgatory have respected the reserve of the Council of Trent, interpreting the notion of fire in a metaphorical sense, and the temporal aspect in terms of intensity.[3]

Some Protestants have accepted prayer for the dead, an intermediate state of purification, and even the term "purgatory". William Forbes, the first Scottish Episcopal Bishop of Edinburgh, affirmed prayer for the dead and described an intermediate state where the soul is purified by its fervent longing for God.[3]Anglican apologist C. S. Lewis believed in purgatory, if not in what the Reformers called "the Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory", and defended the notion.[66] Other Anglicans, in particular Anglo-Catholics (such as the Guild of All Souls), profess belief in purgatory.

Later ideas about purgatory

Questions already discussed among theologians since the Middle Ages continued to be developed. One is whether the souls in purgatory can pray for the living. When considering whether the saints in heaven pray for us,[67] Saint Thomas Aquinas said that the souls in purgatory cannot. According to the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Saint Robert Bellarmine (1542 – 1621) advocated petitioning the souls in purgatory to pray for one,[3] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, on the contrary, Saint Robert Bellarmine (in De Purgatorio, lib. II, xv), while finding unconvincing the reason given by Saint Thomas Aquinas, said that, ordinarily speaking, it is superfluous to invoke the prayers of those in purgatory, "for they are ignorant of our circumstances and condition." The Catholic Encyclopedia attributes instead to the theologian Francisco Suárez (in De poenit., disp. xlvii, s. 2, n. 9) the opinion "that the souls in purgatory are holy, are dear to God, love us with a true love and are mindful of our wants; that they know in a general way our necessities and our dangers, and how great is our need of divine help and divine grace".

Related beliefs continued to grow, such as the Sabbatine privilege, which appeared in the second half of the fifteenth century, the wondrous powers for releasing souls from purgatory of a prayer of uncertain date attributed to Gertrude the Great. There were accounts too of souls in purgatory passing "their purification in the air, or by their graves, or near altars where the Blessed Sacrament is, or in the rooms of those who pray for them, or amid the scenes of their former vanity and frivolity".[68]

Purgatory themes have also been prominent in various works of literature, such as Shakespeare's Hamlet (1603), Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol, and the European ghost-story tradition in general.[69]

Footnotes

- ^ [1]

- ^ EB article on Purgatory

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 Cite error: The named reference "Oxford" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ EB

- ^ [2]

- ^ EB

- ^ http://www.vatican.va/archive/catechism/p123a12.htm#IV

- ^ http://www.vatican.va/archive/catechism/p123a12.htm# IVsouls of those who die in a state of mortal sin descend into hell, where they suffer the punishments of hell

- ^ http://www.vatican.va/archive/catechism/p123a12.htm#IV

- ^ CCC 1854

- ^ CCC 1855

- ^ CCC 1861

- ^ CCC 1863

- ^ [3]

- ^ Bainton, 60; Brecht, 1:182; Kittelson, 104.

- ^ Audience of 4 August 1999

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]

- ^ Article 5

- ^ Confession of Dositheus, Decree 18

- ^ Cabrol and Leclercq, Monumenta Ecclesiæ Liturgica. Volume I: Reliquiæ Liturgicæ Vetustissimæ (Paris, 1900-2) pp. ci-cvi, cxxxix.

- ^ George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106

- ^ Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106; cf. Pastor I, iii. 7, also Ambrose, De Excessu fratris Satyri 80

- ^ Gerald O' Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 217

- ^ Cabrol and Leclercq, Monumenta Ecclesiæ Liturgica. Volume I: Reliquiæ Liturgicæ Vetustissimæ (Paris, 1900-2) pp. ci-cvi, cxxxix.

- ^ Augustine, De Civitate Dei, 21. 24, etc.

- ^ Acts of Paul and Thecla, 8:5-7

- ^ The Passion of the Holy Martyrs Perpetua and Felicity, 2:3-4; "At St. Augustine's time, the Acts were still held in such esteem that he has to warn his listeners not to put them on a level with the canonical Scriptures (De anima et eius origine I, 10, 12)" – ([http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/actsperpetua.html J. Quasten: Patrology, vol. 1, p. 181).

- ^ Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106

- ^ Confessions, Book Six, Chapter XI

- ^ Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27.

- ^ Anthony Dragani, From East to West

- ^ Christian Dogmatics vol. 2 (Philadelphia : Fortress Press, 1984) p. 503; cf. Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.31.2, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers eds. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979) 1:560 cf. 5.36.2 / 1:567; cf. George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 107

- ^ Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; cf. Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London, Williams & Norgate, 1995) p. 337; Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 6:14

- ^ Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) p. 53; cf. Leviticus 10:1–2, Deuteronomy 32:22, 1Corinthians 3:10–15; Origen, in arguing against soul sleep, stated that the souls of the elect immediately entered paradise unless not yet purified, in which case they passed into a state of punishment, a penal fire, which is to be conceived as a place of purification — see Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London: Williams & Norgate, 1905) p. 377. read online.

- ^ Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) pp. 55-57; cf. Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 7:6 and 5:14

- ^ Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; cf. Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London, Williams & Norgate, 1995) p. 296 n. 1; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912); Tertullian De Anima

- ^ A. J. Visser, "A Bird's-Eye View of Ancient Christian Eschatology", in Numen (1967) p. 13

- ^ A. J. Visser, "A Bird's-Eye View of Ancient Christian Eschatology", in Numen (1967) p. 13

- ^ Adolf von Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London: Williams & Norgate, 1905) p. 296 n. 1. read online

- ^ For example, St. Cyprian (d. 258), Letters 51:20; also St. John Chrysostom (c. 347-407), Homily on First Corinthians 41:5, and his Homily on Philippians 3:9-10. See Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; and Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36.

- ^ Vita Gregorii, ed. B. Colgrave, chapter 26 (see also Colgrave's introduction p. 51); John the Deacon, Life of Saint Gregory, IV, 70.

- ^ Matthew 12:32

- ^ Gregory the Great, Dialogues 4, 39: PL 77, 396; cf. Matthew 12:31

- ^ Peter Brown, Rise of Western Christendom" (Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 2003) p. 258; cf. Gregory the Great, Dialogues 4.42.3

- ^ Brown, Rise of Western Christendom (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003) p. 259; cf. Vision of Fursa 8.16, 16.5

- ^ Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica 3.19

- ^ George Cross, "The Medieval Catholic Doctrine of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 192

- ^ George Cross, "The Medieval Catholic Doctrine of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 192

- ^ Observance of the feast existed earlier in local forms: in the sixth century, Benedictine monasteries commemorated the deceased members at Whitsuntide, and, in the next century, there was in Spain a similar celebration on another day; see the Catholic Encyclopedia. The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates several All Souls' Days in the year.

- ^ C. S. Watkins, "Sin, penance and purgatory in the Anglo-Norman realm: the evidence of visions and ghost stories", in Past and Present 175 (May 2002) pp. 3-33.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 339.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), p338.

- ^ Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), p342; quoted passage is from G. A. Lester, Three Late Medieval Morality Plays, p. 102, lines 912-13.

- ^ purgatory. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 1, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-260349

- ^ Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984)

- ^ Alan E. Bernstein, "Review of La naissance du purgatoire", in "Speculum" (1984), p. 181.

- ^ Cf. From East to West

- ^ The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999) p. 201; cf. Orthodoxinfo.com, The Orthodox Response to the Latin Doctrine of Purgatory

- ^ Denzinger 1304 (old numbering, 693)

- ^ The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999) p. 202

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 119

- ^ +Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 580; cf. Koslofsky, Reformation of the Dead pp. 34-39

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) pp. 580-581; cf. Koslofsky, Reformation of the Dead p. 48

- ^ While saying that "the Reformers had good reasons for throwing doubt on the 'Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory' as that Romish doctrine had then become", Lewis stated: "I believe in Purgatory … Our souls demand Purgatory, don't they? Would it not break the heart if God said to us, 'It is true, my son, that your breath smells and your rags drip with mud and slime, but we are charitable here and no one will upbraid you with these things, nor draw away from you. Enter into the joy'? Should we not reply, 'With submission, sir, and if there is no objection, I'd rather be cleaned first.' 'It may hurt, you know' – 'Even so, sir.' I assume that the process of purification will normally involve suffering. Partly from tradition; partly because most real good that has been done me in this life has involved it. But I don't think the suffering is the purpose of the purgation."Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, chapter 20. Extracts may be read at Angelfire and café theology.

- ^ Summa Theologica II-II:83:11

- ^ Opus Sanctorum Angelorum

- ^ purgatory. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 1, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-260349

See also

|

External links

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1030-1032

- CatholicBridge.com, Purgatory — Ecumenical article by David MacDonald concerning Evangelical and Catholic belief

- Catholic Answers, Purgatory — Catholic apologetic article

- NewAdvent.org, Purgatory — 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article

- bringyou.to/apologetics — Readings from the Church Fathers and other sources on Purgatory, by Phil Porvaznik

- EWTN.com library, Heaven, Hell and Purgatory according to Pope John Paul II — Articles from the newspaper of the Holy See, L'Osservatore Romano, July-August 1999

- JewishEncyclopedia.com, Purgatory — Article by Kaufmann Kohler in the online Jewish Encyclopedia

- New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Purgatory — Article by C. A. Beckwith in the 19th century Protestant encyclopedia (ed. Philip Schaff)

- Purgatory account in the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Purgatory article in Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

- I Believe in Purgatory... — excerpt from C. S. Lewis's Letters To Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, chapter 20

- Frequently Asked Questions at Holy Souls Online

- Purgatory and praying for the dead on Catholic Apologetic

- "Prisoner of the King: Thoughts on the Catholic Doctrine of Purgatory", H. J. Coleridge, 1889. retrieved 24 May 2007

- Three Purgatory Poems, a scholarly history of Purgatory from Medieval Institute Publications