User:Tpoas/沙盒

基础备份。

| 古典晚期罗马军队 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 存在時期 | 公元284年至480年 (西部) 或者是公元640年(东部) |

| 國家或地區 | 罗马帝国 |

| 部門 | 军队 |

| 規模 | 大约在400,000–600,000左右 |

| 建制的单位类型 | 御林军, 罗马中央军, 罗马野战军, 罗马边防军, 蛮盟佣兵 |

| 參與戰役 | 萨塔拉之战 (298), 斯特拉斯堡战役 (357), 泰西封战役 (363), 亚德里安堡战役 (378) 和沙隆战役 (451) |

在现代学术中, 古典晚期罗马军队说法始于284年即位的戴克里先,并于476年随着罗慕路斯·奥古斯都的废位而结束, 囊括了整个西帝国的多米那特制统治时期. 在395-476期间,罗马帝国西半部的军队逐渐解体, 而东帝国,或者被称为东罗马军队 (或早期的拜占庭军队) 在规模和结构上基本保持完整,一直持续到查士丁尼统治的结束(公元527-565年).[1]

元首制军队(30 BC – 284 AD)由于混乱的3世纪而经历了重大变革. 与元首制部队不同,4世纪的军队严重依赖征兵其士兵的报酬远低于2世纪。 来自帝国以外的蛮族提供了比第一/二世纪军队更高比例的新兵,但几乎没有证据表明这对军队的作战表现产生了不利影响。

学术上对4世纪军队规模的估计差异很大,范围从大约400,000到超过100万不等(与2世纪时期规模相似,或者大2至3倍).[2] 这是由于当时的参考依据过于碎片化,不像2世纪军队拥有完整的记录文档。

在四帝共治下,与地方总督军政合一的元首制不同,新制度是军政分离的。

与2世纪军队相比,罗马军队结构上的主要变化是建立了规模庞大的常规卫戍部队(comitatus praesentales), 作为精锐的中央军,其规模在2万至3万之间。他们通常驻扎于京畿: (东部是君士坦丁堡, 而西部则是米兰),因此远离帝国的边疆。这些军队的主要功能是阻止 皇位的觊觎者, 通常由皇帝亲自指挥。军团 被分成较小的单位,规模与元首制的辅助军团相当。步兵 采用了比元首制军队的骑兵更具保护性的装备。

与元首制的军队相比,骑兵在后期军队中的作用似乎没有明显的加强。有证据表明,骑兵与二世纪时期的人数和比例大致相同,其战术角色和声望仍然相似。 然而,晚期罗马军队的骑兵 衍生出更加专一化功能的单位, 例如(甲胄冲击骑兵和具装冲击骑兵) 和弓骑兵。[3]在4世纪后期,骑兵因其在三场重大战役中的糟糕表现而获得无能和怯懦的声誉。相比之下,步兵保持其传统的卓越声誉。

3世纪和4世纪,许多现有的边境堡垒得到了升级,使它们更具防御性,并建造了具有更强防御能力的新堡垒。对这一趋势的解释引发了一场持续的争论,即军队是采用了 纵深防御战略 还是继续采用与早期元首制相同的“前瞻性防御”姿态。 后期军队防御姿态的许多因素与前线防御相似,例如堡垒的前沿位置,频繁的跨境行动以及盟军野蛮部落的外部缓冲区。无论防御策略如何,它在防止日耳曼蛮族的入侵方面显然不如1世纪和2世纪那么成功。这可能是由于野蛮人在边境的压力愈发加强,或者是为了将战斗力最强的部队留在中央而使边防部队得不到足够的支持所导致的。

古典晚期罗马帝国军队的起源

我们关于4世纪军队部署的大部分证据都包含在一份文件中,即 罗马百官志,记录了395-420期间罗马所有公共事务官员(军事民政都囊括在内)的手册。百官志的主要缺点是它缺乏任何人员数据,以以至于无法估计军队规模。它也是在4世纪末编制的;因此很难确定之前时间点的情况。然而,由于缺乏其他证据,百官志仍然是军队结构的核心来源。[4] 百官志也遭受了严重的资料缺失,并且在几个世纪的誊写抄录中使得中间的问题激增。

4世纪军队的主要文学来源是阿米安努斯所撰写的Res Gestae《历史》,其幸存的书籍涵盖353至378年期间的罗马军队。玛尔切利努斯本人是一名资深士兵,被学者视为可靠和宝贵的资源。但他在很大程度上无法弥补百官志在军队单位以及实力方面的数据缺失,因为他很少有具体数字在内。第三个主要来源是5至6世纪之间在东罗马帝国下达的帝国法令的集合: 狄奥多西法典 (438)和民法大全 (528–39)。这些罗马法律的汇编可以追溯到公元4世纪,其中包含许多与晚期帝国军队内对督查和管理的各类法规。

De re militari,即《军事论》, 由4世纪晚期或5世纪初的作家维盖提乌斯斯撰写,其中包含有关晚期帝国军队的大量信息,尽管其重点全在共和制和元首制时期的军队上。然而,维吉蒂乌斯严重缺乏军事经验导致写出来的东西极不可靠。例如,他说军队在4世纪晚期放弃了盔甲和头盔(他提供荒谬的解释,声称这些装备太重了),这与雕塑和其他艺术上的证据相矛盾。[5] 一般来说,他的说法太过于天马行空,除非能够得到其他史料的证实。

与1世纪和2世纪相比,古典晚期帝国军队的研究者们必须面对3世纪之后关于军队的相关记录严重缺失的问题。因为203年之后帝国不再向役满到期的辅助军团士兵发放证书 (因为来自于卡拉卡拉的“善意”当时几乎所有人都已经是罗马公民)。此外,罗马军人的墓碑,祭坛和其他神殿的数量大幅减少。建筑材料(例如大理石砖上)上带有军队士兵们的浮雕的现象也趋于绝迹。 但这种趋势不应被视为军队在行政管理上走向简单粗暴。来自埃及的莎草纸文稿证据表明,军队在4世纪仍保留详细的书面记录(其中大部分由于有机物分解而丢失)。最有可能的是,石制碑文的减少是由于当时风俗的变化,比如说受到蛮族兵员增加和兴起的基督教的影响。[6] 石制碑文的缺乏给我们对晚期罗马帝国的军队的研究留下了严重的史料缺失,并使得许多结论无法被确定。

A.H.M. Jones所著的The Later Roman Empire, 284-602 (LRE)开创了全新的关于现代对古典晚期罗马军队的研究 . 这本1964年出版的书因为其丰富的细节和文献资料至今仍然是学者们极为重要的研究材料。当然这本书的问题在于其年代久远,在出版之后的数十年间学术界已经出现了大量的考古工作以及相关的研究。

四世纪军队的发展

一切的基础:元首制时期的罗马军队

元首制正规军由其创始人奥古斯都 (30 BC – 14 AD在位)建立并使之保留至3世纪末。 正规军由两种不同的军团组成,两个军团主要依靠募兵。

作为精英的罗马军团是大型步兵编队,数量在25到33之间。每个军团有5,500名兵员(所有步兵军团都保留了一支120人规模的小型骑兵部队)只招收罗马公民.[7] 辅助兵团 由大约400个更小的单位(大队)组成。每个大队500人(少数可达1000人),分为大约100队骑兵,100队步兵和200队混合骑兵/步兵部队或者同规模部队。[8] 一些辅助军团被指定为“弓兵团”,这意味着它们专门用于对敌弓箭射击。 因此,辅助军团几乎包含了所有罗马军队的骑兵和弓箭手,以及(从1世纪后期开始)与军团大致相同数量的步兵。[9]辅助步兵主要在自由民'内招募,': 那些没有公民权的非奴隶罗马住民,但是同时也接收罗马公民和住在帝国境外的巴巴里/蛮族。[10] 在那段时期,罗马军团和辅助军团几乎都部署在边境省份。[11] 能直属于皇帝并被皇帝在短时间内快速集结指挥的只有10000人左右的精英罗马禁卫军。[12]

直到公元3世纪,军队的高级军官几乎都来自于意大利贵族。这些贵族被分为两类,一类是正式的有身份的世袭贵族 (ordo senatorius), 由罗马元老院的600名成员和他们的儿孙组成,以及数以千计的罗马骑士们.

世袭元老和罗马骑士将军政服役结合,组成了具有罗马特色的晋升体系, 通常从罗马的一个初级行政职位开始,随后在军队中任职5至10年,最后在罗马或者各个行省担任高阶职务。[13] 这个由不到一万人所组成的小型,紧密结合的统治寡头集团在8000万居民的帝国中垄断了政治,军事和经济权力,并成功地稳定了整个帝国。 在其存在的最初200年(公元前30年 – 公元180年), 帝国只遭受了一次重大内乱(即四帝之年).其余时间极少数图谋不轨的行省总督的僭越行为都会被迅速镇压。

在军中,世袭贵族 (senatorii)通常担任以下职位:

- (a) legatus Augusti pro praetore(边境行省的总督,他是部署在那里的军队的总司令,也同时是该地区民政部门的负责人)

- (b) legatus legionis(罗马军团长)

- (c) tribunus militum laticlavius (罗马副军团长)。[14]

罗马骑士通常担任以下职位:

- (a) 埃及和一些非重要行省的总督

- (b) praefecti praetorio (罗马禁卫军的指挥官,仅两位)

- (c) praefectus castrorum (军团内的宿营长,军团内的三把手)及军团内其余的五名tribuni militum (军事保民官,高级参谋军官)

- (d) 辅助军团的指挥官praefecti[15]

到了1世纪末,帝国内形成了一个特别的由非意大利人的军人所组成的罗马骑士阶层,肇因起源于皇帝在他每一年执政结束时将每个军团的primuspilus (首席百夫长)提升到骑士等级。这会使大约30名职业军人,大多数是非意大利人,加入贵族阶层。[16] 他们要比意大利的同僚们贫穷得多,毕竟这些意大利的同僚很多都仰赖于他们所凭依的家族。 其中突出的是罗马化的伊利里亚人,是居住在帝国境内各省,例如潘诺尼亚 (今匈牙利/克罗地亚/斯洛文尼亚), 达尔马提亚 (今克罗地亚/波斯尼亚)和 上默西亚 的(今塞尔维亚)伊利里亚语部落的后裔,以及邻近的[默西亞 (羅馬行省)|下默西亚]] (保加利亚北部)和马其顿 行省居住的色雷斯人。从图密善时期(81–96在位)开始, 当超过一半的罗马军队部署在多瑙河地区时,伊利里亚和色雷斯省成为最重要的辅助兵团募兵基地,后来也成为罗马军团的最重要的兵员来源。[17]

三世纪时期的发展

3世纪初军队的开创性发展是由 卡拉卡拉皇帝(211-18在位)颁布的212年的安东尼努斯敕令所带来。这赋予了帝国所有自由居民罗马公民身份,结束了无公民权自由民的二等地位。[19] 这条法令打破了罗马公民的罗马军团和自由民组成的辅助军团之间的区别。在1世纪和2世纪,军团是意大利“宗主国”在其藩属中占主导地位的象征(和担保人)。在3世纪,他们不再在社会上优于那些外来者们(尽管他们可能在军事方面保留了他们的精英地位),同时军团特殊的盔甲和装备(比如说 罗马环片甲)也被逐步淘汰。[20]

因为意大利世袭贵族在军队中的高层逐渐被出身于自由民的前头等百夫长所取代,高级文职和军职之间交替任职的传统晋升体系在2到3世纪的交际于是被逐渐废弃。.[21]在公元3世纪,只有10%的辅助军团的长官来自于意大利的罗马骑士,而前两个世纪的比例则是大多数。[22] 与此同时,垄断军方上层的世袭贵族也被罗马骑士所取代。塞普蒂米乌斯·塞维鲁 (197至211年间在位) 任命了三个出身于自由民的首席百夫长作为他所组建的三支新军团的新长官,而加里恩努斯 (260–68)对所有其他军团也如法炮制, 给予他们praefectus pro legato ("代行军团长官")的头衔.[23][24] 这些新晋的罗马骑士团体的崛起为军队提供了更专业的将领,但却促进了雄心勃勃的将军的军事叛乱的概率。 3世纪发生了无数次政变和内战。很少有3世纪的皇帝能长留帝位或是寿终正寝。[25]

皇帝对频繁产生的不安全状况迅速做出了回应,他们逐渐建立了一支可以快速集结的部队。这些被称为 扈从军 (原意"护卫", 之后衍生出英文单词"committee",即委员会). 除了帝国禁卫军的10,000名成员,塞普蒂米乌斯·塞维鲁还设立了第二帕提亚军团. 驻扎在罗马附近的阿尔巴诺拉齐亚莱 , 这是自奥古斯都以来第一支驻扎在意大利的军团。他从边境驻扎的骑兵队里调剂人员,将equites singulares Augusti, 即帝国护卫骑兵的数量增加了一倍,使数量增加到了2000人。[26] 他的扈从军规模因此达到了17000人,相当于31个步兵大队和11个骑兵大队。[27] 之后的皇帝们一直采取强化中央军的政策,这个趋势在君士坦丁一世(312–337年在位),他的扈从军规模可能已有10万人,达到了军队总数的四分之一。[28]

在加里恩努斯统治时期,一些高级军官被他任命为 督军 (复数形式: duces, 即中世纪公爵的起源), 以指挥所有的护卫骑兵。军队内包括了equites promoti (从军团中分离的骑兵支队),以及伊利里亚轻骑兵(equites Dalmatarum)和盟邦蛮族骑兵(equites foederati).[24] 在君士坦丁一世的统治下,骑兵的长官被封予骑兵长官的头衔(magister equitum)magister equitum, 在共和国时期这一职责由狄克推多的副手担任.[29] 但根据过去的学者们所描述,早期这个职位并未暗示那个时期有过一支独立的纯骑兵军队的存在。两名骑兵长官麾下的军队混有步兵和骑兵,而且仍以步兵为主。[27]

3世纪军团的规模逐渐缩小,甚至还有一些辅助单位夹杂其中。军团被分解成较小的单位,这可以通过在英国遗留下来的传统大型基地遗址来证明,他们的规模随着时间逐渐缩小,最终被放弃使用。[30] 此外,从2世纪开始,一些从母单位内被分离出来的子单位最终形成了新的作战单位, 例如2世纪初位于达契亚的伊利里亚骑兵分队vexillatio equitum Illyricorum[31]和驻扎在英国的equites promoti[24]与numerus Hnaufridi。[32] 这导致了4世纪各种新单位类型的衍生,这些作战单位的规模通常少于元首制时期的军队建制。 例如,在2世纪, 布旗队vexillatio (衍生自 vexillum 即"军旗"之意) 是从罗马军团/辅助军团分离出的部队单位,既可以是步兵也可以是骑兵。而在公元4世纪,它通常作为精英骑兵团的建制出现。[33]

从3世纪开始军队内开始有记录出现以蛮族部落的名字命名的正规小型部队单位 (而不是以自由民部落的名字为名). 这些部队是蛮盟佣兵foederati (对罗马有军事义务的盟军)转化过来的正式部队建制,这一趋势将在4世纪越发明显。[34] 驻扎在不列颠的第一萨尔马提亚骑兵大队, 可能是由马可·奥勒留在175年送去驻扎哈德良长城的5,500名萨尔马提亚骑兵俘虏中的一部分组成的。 [35] 当然至少在公元3世纪时期,还没有史料充分证明非常规建制的蛮族民兵部队成为了元首制时期罗马军队的一部分。[36]

三世纪危机

3世纪中叶,帝国陷入极为严重的军事和经济危机 251-271的一系列军事上的灾难表现使得高卢,阿尔卑斯地区和意大利,巴尔干半岛和东方地区被阿勒曼人,萨尔马提亚人,哥特人和波斯人占领,几乎导致帝国解体。[37] 与此同时,罗马军队还要努力应对毁灭性瘟疫的影响,现在该流行病被认为是天花, 251年始于塞浦路斯的塞浦路斯大瘟疫,并且在270年时仍然在肆虐,还可能带走了克劳狄二世 皇帝的性命(268–270年间在位).[38] 而根据二世纪后期安敦尼疫病爆发时期所遗留下来的史料来看,极有可能就是天花,当时帝国内15%-30%的居民因此病歿。[39] 根据佐西穆斯的记载,实际情况可能远糟于此。[40] 军队以及他们所居住的(同时主要是招募的来源地)边境省份,因为他们人员集中且被频繁调动,使得这些地区成为了瘟疫的重灾区[41]

3世纪的危机开始了社会经济影响的连锁反应,这对古典晚期军队的发展具有决定性作用。由于瘟疫造成的严重破坏和税基锐减的二者结合使得帝国政府破产,帝国中央决定生产大量成色低下的货币,比如安东尼尼安努斯,作为作为当时支付帝国军队薪水的银币, 在215年到该世纪的60年代的数十年里成色降低了95%. 即使用相同质量的贵金属可以制作20倍的硬币。[42] 这导致价格疯狂通胀:例如,戴克里先的小麦价格是元首制时期的67倍。[43] 货币经济崩溃,军队不得不依靠征收食品换取补给以维持。[44] 军队征税毫无公平可言,使得他们所驻扎的边境省份遭到毁灭性的打击。[45] 士兵的薪水毫无价值可言,这使得军队的新兵减少到仅能维持军队建制存在的水平。[46] 这样的状况使得境内的公民不愿从军,帝国政府被迫使用强制征兵的手段[47] 而同时因为瘟疫又减少了大量的人口,帝国不得不大量招募蛮族进入军队。到4世纪中叶,蛮族兵员达到了新兵总数的四分之一(精英军团内甚至超过三分之一),比1世纪和2世纪的比例都要高得多。[48]

多瑙河军官团

到了公元3世纪,罗马化的伊利里亚人和色雷斯人, 大多来自罗马骑士们及他们的后代,垄断了军队的高级官员位置。[49] 直到最后,多瑙河军事高官们夺取了对国家本身的控制权。268年加里恩努斯 (260–268年间在位) 被伊利里亚和达契亚的高级军官组织的政变推翻,其中包括了他的继任者克劳狄二世和奥勒良 (270–275年间在位).[50] 以及他们的继任者普罗布斯 (276–282年间在位),戴克里先 (284–305年间在位)以及四帝共治的同僚们组成的永久性的军政府。他们可以是出生在同一个省,(有些甚至出生在同一个城市,比如上默西亚的军队驻地西尔米乌姆)的老乡们,或者是曾在同一军团中服役的同僚们。[17]

奥勒良即位后军政府用一连串的胜利扭转了251-71的军事灾难,其中最为出名的的是克劳狄二世在纳伊苏斯战役 战胜了规模极为庞大的哥特人部队, 这对哥特人打击甚大,以至于哥特人直到一个世纪之后的亚德里安堡战役 (378)之后才再次严重威胁帝国。[51]

伊利里亚皇帝或多瑙河皇帝特别关注在危机期间由于瘟疫和野蛮入侵造成的边境省份人口减少现象,因为这个问题在他们自己所在的多瑙河省份尤其严重。 因为缺乏人力,这些省份的耕地大量荒废。[52] 因此,为了应对人口减少对军队招募和供应构成的严重威胁,伊利里亚军政府采取了一项积极的政策,将被击败的蛮族部落居民大规模地重新安置在帝国领土上。 奥勒良在272年将大量卡尔皮人迁了潘诺尼亚。[53] (此外,到275年,他撤销了达契亚省, 将整个省人口迁移到了默西亚,动机与之前相同).[54] 记录档上有记载提到他的继任者普罗布斯在279、280年将100,000名 巴斯塔奈人以及后来还有相当数量的格皮德人, 哥特人和萨尔马提亚人迁移至默西亚.[55] 戴克里先之后持续地执行这项政策,根据维克多的记载,他转移了297个大量的巴斯塔奈,萨尔马提亚和卡尔皮的部落到边境省份。[53][56] 虽然这些人在帝国定居的确切条件未知(说法多种多样),但共同特征是给予蛮族土地换来的就是兵役或者远高于其他省份份额的征兵名额。从罗马政府的角度来看,这项政策有三重好处,即削弱敌对部落,重建受瘟疫蹂躏的边境省份(将其废弃的田地重新养护起来)并为军队提供一流的新兵。这也受到了蛮族囚犯的欢迎,他们对帝国可能会给予他们土地的政策感到高兴。在4世纪,这些蛮族群体被称为军户.[34]

伊利里亚王朝出的皇帝统治帝国一个多世纪,直到379年才结束。事实上,直到363年,权力都一直由当初建立军政团体的成员后代所掌握。君士坦丁一世的父亲君士坦提乌斯在戴克里先的四帝共治政府中任职凯撒(西部的副皇帝).[57] 君士坦丁的孙子尤利安统治到363年。这些皇帝将军队成功地恢复到危机前的实力,但他们也只关心军队的需要和利益。他们也与拥有帝国的大部分土地的富裕罗马元老们的家族脱节。这反过来又在罗马贵族中产生了一种与军队疏远的感觉,这种感觉使得从4世纪后期元老们开始抵制军队对帝国的无止境兵员和物资需求。[58]

戴克里先

戴克里先被公认为最伟大的伊利里亚人皇帝。 戴克里先大规模在行政,经济和军事施行的改革旨在为军队提供足够的人力,物资和军事基础设施。[59] 用一位历史学家的话来说, "戴克里先......把整个帝国变成了一个有条不紊的后勤基地" (用以为军队提供补给)。[60]

戴克里先时期的军事指挥结构

戴克里先的行政改革的双重目标是确保政治稳定,并提供必要的官僚和基础设施,以提高军队所需的新兵和兵役。在最高层,戴克里先设立了四帝共治制。这将帝国划分为两个部分,东部和西部,每个部分由奥古斯都(皇帝)统治。每个奥古斯都将依次任命一名名为凯撒的副手,他将作为他的执政伙伴(每个人都被分配到帝国的四分之一)并指定继任者。因此,这个四人小组可以灵活地应对多重和同时的挑战,并提供合法的继承。[61]当然后者未能实现目标,在3世纪由于多次篡位而造成的灾难性内战仍然在四世纪重演。实际上,如果为每个篡位者提供潜在的大量的护卫部队来强制执行他的主张,情况可能会变得更糟。戴克里先自己退休后就眼睁睁地看到他的继任者为了权力而互相争斗。但是,将帝国划分为东西两半,同时认识到地理和文化现实,被证明是持久的;东西分治仍然使得帝国为一整体,不过在395之后便成为永久性的分裂。

戴克里先改革了省政府,建立了一个三层的省级层级,取代了以前的单层结构。最初的42个省份的数量几乎增加了两倍,大约在120上下。 [來源請求]这些省份归属于12个区域,被称为管区,每个管区都有一名代理官, 然后再归属于4个近卫大区, 以对应于分配给四位君主(凯撒和奥古斯都)的辖区, 每个领土都由一名近卫司政官 (请勿与具有相同头衔的罗马禁卫军长官的名称混淆)。级政府这种分割的目的是通过减少他们各自控制的力量来减少地方总督军事反叛的可能性。[62]

此外,为了提供更专业的军事领导,戴克里先将军队体系从行省的民政机构中分离出来。边境省份的省长被剥夺了驻扎在那里的部队的指挥权,转而将这全力交给称为 duces limitis ("边防督军"),在戴克里先时期可能任命了大约20个边境督军。[52] 大多数的督军只指挥一个省份的驻军,但少数几个督军控制了超过一个省份的督军,例如第一潘诺尼亚和诺里奇行省督军,即dux Pannoniae I et Norici.[63] 然而,在更高的层次上,军事和行政指挥仍然统一在管区代理官和近卫司政官名下.[62] 此外,戴克里先还完成了对元老院阶级的排挤,元老院阶级仍以意大利贵族为主导,除意大利外,元老院贵族不得担任一切高级军事指挥和最高行政职务。[64]

人力

为确保军队获得足够的新兵,戴克里先施行了自[[罗马共和国|罗马共和国]时代以来首次对罗马公民进行系统的年度征兵制度。此外他可能颁发了一道最早记载于313年的法令,强制正在服役的士兵和退伍军人的子弟入伍。[47]

戴克里先时期,军团的数量,可能还有其他军事单位建制,增加了一倍多。[65] 都增加了一倍多。 但军队的总体规模不可能增加得那么多,因为单位兵力似乎减少了,在某些情况下还大大减少了。例如军团编制,相比于元首制时期的5500人规模,戴克里先的新军团只有1000人。也就是说,新军团可能只增加了军团总人数的15%左右。[66][67] 即便如此,学者们普遍认为戴克里先大幅增加了军队人数,至少增加了33%。[68]

补给

戴克里先主要关注的是将向军队提供粮食供应置于合理和可持续的基础上。为此,皇帝结束了对军队能够任意在当地征收粮食税(indictiones)的权利, 因为军队的负担主要落在边疆各省,这样做会毁了当地的经济。他建立了一种每年定期征税 indictiones ("税款征收")的制度,要求征收的税款预先设定为5年,并与各省的耕地数量有关,并以全帝国范围内的土地、农民和牲畜的彻底普查为后盾。[69] 为了解决某些地区农村人口减少的问题(以及随之而来的粮食减产),他下令在元首制时期可以自由迁徙的农民们,绝不能离开他们在普查中所登记的地方(法律术语称'origo'). 这项措施将佃民及其后代捆绑在了他们的地主的庄园内。[70]

军事基础设施

在恢复军队规模的同时,戴克里先的努力和资源集中在沿着帝国所有边界的防御基础设施进行大规模升级改造,包括新建堡垒和战略性军用道路。[71]

君士坦丁一世

在312年击败马克森提乌斯后,君士坦丁解散了罗马禁卫军,结束了后者长达300年的存在。[72]虽然当时的原因是禁卫军支持他的竞争对手马克森提乌斯,但因为皇帝现在很少居住在罗马,驻扎在那儿的军队也就毫无意义了。原先护卫皇帝的禁军骑兵,equites singulares Augusti,即罗马禁卫军附属骑兵队,也就被御林军所取代。这些精锐的骑兵团在君士坦丁即位时便存在,可能是由戴克里先创立的。[73]

君士坦丁将他的护卫军队拓展成一支占有永久主导地位的军事力量。他将边境的部分军力回收并创建了两支新的部队:更多的骑兵单位"布旗队"和步兵单位"辅助步兵团"。扩大规模后的扈从军由两名新军官指挥,一位步军长官负责所有的步兵部队,一位骑兵长官负责骑兵部队。扈从军被正式命名为野战军 以区别于(边防军).[62] 君士坦丁的扈从军规模不详,但根据佐西穆斯的说法,君士坦丁在对马克森提乌斯的战争中动员了98,000名士兵。[28] 很有可能军队中的大多数士兵都直接来于他的扈从军.[29] 如果接受君士坦丁军队人数约为40万的说法,那么这些士兵约占正规军总数的四分之一。[74] 当世学者们一直在讨论为何君士坦丁要保留如此庞大规模的扈从军,一般传统观点认为,君士坦丁将其认作一种战略储备以用于对抗大规模入侵帝国腹地的蛮族军队,或者作为跨越边界征讨蛮族的大型远征军的主力。但更多的近代学者则认为其主要功能是为了防止潜在的篡位者而做的保险措施。[27] (请参照下面会论及的古典晚期罗马军队的战略).

君士坦丁一世完成了军事机构与行政结构的分离。管区代理官和近卫司政官失去了他们的战地指挥权,成为了纯粹的行政官员。然而他们在军队事务中发挥了核心作用,因为他们仍然负责部队兵员招募,军饷以及最重要的提供补给。[75] 但是当时的边区督军究竟是直接汇报给皇帝,还是扈从军的两位长官,到现在仍然未知。

此外,君士坦丁似乎重新组织了多瑙河沿岸的边防部队,分别用新的骑兵连“cunei”和辅助军团“auxilia”代替原来的骑兵大队“alae”和步兵大队“cohortes”[62] 目前还不清楚新式部队与旧式部队有何不同,但驻扎在边境的部队 (相比于扈从军内的建制)要小上许多,只为原来的一半左右。[76] 但除了多瑙河/伊利里亚以外的地区还是得以保留了旧的建制。[77]

5世纪的历史学家佐西穆斯强烈批评他建立过于庞大的扈从军的做法,指责君士坦丁破坏了他的前任戴克里先的加强边防的工作: "由于戴克里先的远见卓识,罗马帝国的边境到处都是城市、堡垒和塔楼... 整个军队都驻扎在边境,所以蛮族不可能突破...但君士坦丁把大部分军队从边境撤走,驻扎在不需要保护的城市里,从而毁掉了这一防御体系。"[78] 佐西穆斯的批评可能是过分的,因为在戴克里先时代扈从军就已经存在,君士坦丁做的无非是为了扩张扈从军组建了全新的军团并合并了旧有的建制[79] 然而君士坦丁的扈从军的主要来源便是从边境调动回来的边防军人们[66] 撤回大批的边防部队的行为终究还是提高了蛮族大规模突破边境进入帝国腹地的风险。[80]

四世纪后期

随着337年君士坦丁的去世,他的三个儿子君士坦丁二世, 君士坦斯一世 and 君士坦提乌斯二世,将帝国三分,分别统治西部(高卢,英国和西班牙),中部(意大利,非洲和巴尔干半岛)和东部。他们每个人都接收了他们父亲的扈从军的一部分.到了353年,只有君士坦提乌斯存活下来, 但这三支扈从军永久性地驻扎了下来,分别在高卢,伊利里亚和东部。 到了四世纪六十年代,边境督军都直接向当地的中央扈从军长官直接汇报工作。[72] 然而除了地区性的扈从军外, 君士坦提乌斯还保留了一支随时可动用的部队, 被称之为 常备扈从军 (Comitatus Praesentalis).[81] 而三个扈从军所在的地区的扈从军的数量却在不断增加,直到百官志 ( 约公元400年),西部有6支野战军,而东部则有3支。[62] 这些对应于西部的边境管区,在西部则对应不列颠,三部高卢(阿基坦高卢,卢格敦高卢和比利时高卢),伊利里亚西部(潘诺尼亚),阿非利加和西班牙; 在东部则对应着: 伊利里亚东部(达契亚), 色雷斯和东方。相对的扈从军指挥官开始对口于行政部门的长官管区代理官,控制着管区内的所有部队,其中包括了边区督军.[1][82]因此,在这一时间点上,平行的军事/民事行政结构可归纳如下:

| 层级 | 军事长官 | 民政长官 |

|---|---|---|

| 行省 | 边区督军 | 督查官 |

| 管区 | 大元帅 (东部)/野战军司令 (西部) | 管区代理官 |

| 近卫大区 | 奥古斯都/凯撒 | 近卫司政官 |

区域性的扈从军的产生是对君士坦丁强干政策的部分逆转,实际上证明了佐西穆斯对君士坦丁批判,边防军 缺乏中央对此的有效支持。[83]

尽管地区性的扈从军数量激增,不过帝国中央的扈从军仍然存在,在百官志撰写时期有三支常备扈从军的存在, 每支定员20000-30000上下,总计仍有75000人.[84] 如果接受当时军队人数约为35万的说法,扈从军仍占总军队规模的20-25%。不晚于365年且仍然能留在扈从军中的军事单位,一概被统称为中央军 (直译为"来自宫中), 是所谓野战军的高级形式。[81] 于是军队内的部队单位被分为四个等级,代表着不同的质量,声望与薪酬。以降序排列的话便是御林军, 中央军, 野战军和边防军。[85]

军队规模

由于当时留存相当多详细可究的证据,现代学者对公元1世纪和2世纪罗马军队的规模有广泛的学术共识。然而,关于4世纪陆军的规模,众人对此莫衷一是。由于缺乏关于编制人数的证据,导致对陆军后期力量的估计大相径庭, 范围从约400000 (与2世纪大致相同)到100万以上。 主流学者主要分歧在于有些人认为实际是400000的"较低值"以及600000的较高值。[來源請求]

庞大的军队规模假说

一些传统的学者观点认为,4世纪的军队比2世纪的军队大得多,规模应该是原来的两倍。6世纪后期的作家阿伽提乌斯给出了645,000的数字,推测是君士坦丁一世时期的巅峰值。[86] 这个数字可能包括舰队的海军士兵,那陆军人数大致在600,000左右。佐西穆斯将312年包括君士坦丁皇帝在内的所有皇帝的军队总数相加,于是得出了581,000的总数. A.H.M. Jones' 所撰写的古典晚期帝国 (1964), 包含了对罗马古典晚期的军队各类的基础研究,。他以自己对建制兵力的估算方法应用在百官志的所列的单位上,从而得出了600,000的总数。 (海军除外)[87]

然而,琼斯的600,000的数字是基于对边防军人数的估算,可能远高于实际值。琼斯根据戴克里先时期使用的莎草纸所写的工资支给文件证据证明计算了埃及的建制人数。但R. Duncan-Jones对史料进行严格的重新评估后得出的结论是,琼斯的建制人数高估了2-6倍。[88] 例如,琼斯估计边境的军团编制在3000人左右,而其他的单位大致有500人上下。[89] 但Duncan-Jones的修订发现,边境驻扎的军团规模仅为500人, 骑兵大队只有160人,骑兵队只有80人即使考虑到其中一些单位可能是某个大单位的分队,戴克里先的单位兵力很可能远低于早期[90]

特里高德在对拜占庭的军力考察上认可了大规模的古典晚期军队的说法。特里高德认为吕底亚的约安尼斯所给出的389,704人的数据对应的是戴克里先刚继位的285年,[91] 佐西穆斯所给出的581,000人对应的则是312年的数据.[92] Treadgold估计军队的规模在235-285年保持不变,在285-305年迅速增加了50%,在之后的90年间(305-395)大致保持不变[93]

但是特里高德的分析在以下几个方面受到批评:

- 军队规模在235和285之间保持不变的结论似乎难以置信,因为这一时期出现了三世纪危机,在此期间,塞浦路斯大瘟疫的影响,无数的内战和毁灭性的蛮族入侵严重削弱了军队的招募能力。

- 如果吕底亚的约安尼斯给出的39万的数字如果是戴克里先刚开始统治的兵力的话,那么这个数字是值得怀疑的,根据学界的研究,这个数字更像是戴克里先扩员成功后的最高兵力。

- 特里高德声称戴克里先将军队数量增加了50%以上,被另外一名学者希瑟认为难以置信,他指出即使增加三分之一的人力也要付出极大的努力。[94]

- 特里高德的估计是根据佐西穆斯提供的君士坦丁军队的数据得出的, 而佐西穆斯是一个著名的不靠谱的编年史学家[95][96] 无论是在一般情况下,还是在具体数字方面:例如,他报告说,在357年的斯特拉斯堡战役中,有6万名阿勒曼尼人,相比于被当代史学家认为是可靠的马尔切利努斯所给出的6000人的数据,佐西穆斯所给的数据出现了极为明显的夸大。[97]

小型的的军队规模假说

传统的4世纪军队规模大得多的观点在近代已经不受一些历史学家的青睐,因为现有的证据被重新评估,新的证据被发现。修正主义的观点认为,4世纪的军队在高峰期时,其规模与2世纪的军队大致相同,并且在4世纪后期大幅度缩水。 阿伽提亚斯和佐西穆斯的统计数字,如果他们的说法是有效的,那也只可能代表君士坦丁时期的官方预计,而远非实际的力量。微不足道的证据是,后期的部队往往兵力严重不足,实际也许只有官方的三分之二左右。[98] 因此,阿嘉西亚斯在纸面上的600,000可能只不过有400,000左右。后者这个规模与六世纪的吕底亚的约安尼斯所提供的戴克里先时期除去海军水兵的军队总数389,704是吻合的。Lydus的数字比Agathias的数字更可信,因为它的精确性(它是在一份官方文件中发现的),并且它被归于一个特定的时期[2]。[99] 来自帝国边界所出土的考古学证据表明,晚期堡垒的设计目的是为了容纳比其过于元首制时期更少的守军。如果可以使用百官志中列出的堡垒识别此类场地,这些堡垒内部所能容纳的驻军编制人数也同期缩水。可以以戴克里先创建的Legio II Herculia, 第二赫丘利军团为例。比起元首制时期的军团驻地,堡垒只有其七分之一左右,从此可以推断这个军团大概只有750人左右。在多瑙河畔的阿布西纳(Abusina),Cohors III Brittonum,第三不列颠骑兵大队,所驻扎的堡垒只有过去图拉真时期的堡垒的十分之一大小,也由此推断这支大队只有50人左右。必须谨慎对待这些证据,因为在《百官志》中对带有地名的考古遗址的鉴定往往是试探性的,而且有关单位可能是某大单位的分队(《百官志》经常出现同一单位同时出现在两个或三个不同的地点) 不过一般来讲考古学者都从保守角度起见来估计,所以他们一般都会选择保守的角度来对边防军的军事单位规模进行估算。[100] 因此,考古学上发现的证据表明,公元400年的时候,驻扎在不列颠的守军仅有公元200年元首制时期的三分之一(200年时期是55000人左右,400年时期只有17500上下)。[76]

同时,更多的最新研究表明,2世纪的正规军数量比传统上预估的约30万人要高得多。这是因为2世纪的辅助军团人数不仅与1世纪初的罗马军团人数相等,甚至有的时候还会比预估的数字大上50%左右。[8] 甚至有的时候还会比预估的数字大上50%左右。在2世纪末,元首制的军队可能达到近45万的高峰(不包括海军官兵和盟邦的佣兵)。[101] 此外,有证据表明,2世纪部队的实际兵力通常比4世纪部队更接近官方实际数据(约85%)[102]

对整个帝国各个时期的陆军兵力的估计可归纳如下:

| Army corps | 提比略 24 |

哈德良 约130年 |

赛维鲁 211 |

戴克里先 284年开始统治时 |

戴克里先 305年退位时 |

君士坦丁一世 337年 |

百官志 (东部约395年,西部约420年) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 罗马军团 | 125,000[103] | 155,000[104] | 182,000[105] | ||||

| 辅助步兵 | 125,000[106] | 218,000[8] | 250,000[107] | ||||

| 罗马近卫军 | ~~5,000[108] | ~~8,000[109] | ~15,000[109] | ||||

| 罗马军队总数 | 255,000[110] | 381,000[111] | 447,000[112] | 保守估计: 260,000?[113] 特里高德: 389,704[114] |

保守估计: 389,704[115] 特里高德: 581,000[116] |

埃尔顿: 410,000[74] 特里高德: 581,000[117] |

保守估计: 350,000?[118] 特里高德: 514,500[119] |

NOTE: 仅计算常规部队: 蛮盟佣兵和(元首制时期有4-5万规模的)罗马海军不纳入计算

军队结构

4世纪军队包含三种类型的军队: (a) 常备扈从军 (comitatus praesentales)。这些通常是靠近帝国首都(西方的米兰,东方的君士坦丁堡),通常陪同皇帝对外出征。 (b) 管区扈从军 (comitatus) 这些都位于边境或附近的战略地区。 (c) 边防军 (exercitus limitanei).[120]

类型(a)和(b)经常被定义为"机动野战军"。这是因为,与边防军单位不同的是,他们的行动不局限于一个行省。他们毕竟职责不同,这些扈从军是皇帝用来阻止帝国内潜在的篡位者的最终保险: 这样一支强大部队的存在本身就会威慑许多潜在的对手,如果没有,仅靠扈从军往往就足以打败他们.[27] 他们的次要作用是陪同皇帝对外远征,如对外战争或击退大规模的蛮族入侵。[121] 另外一方面,管区的扈从军负责的是在重大入侵的时候支援本地的边防军[122]

高层的指挥架构

帝国东部的指挥结构

百官志对于东帝国的描述要追溯于狄奥多西一世去世时的395年.此时,根据百官志的说法,在东方有2支中央扈从军 (comitatus praesentales),每支军队都是由常备军大元帅指挥, 军方的最高层的一部分,直接对皇帝负责。这两支军队都被算作是中央军。此外在东伊利里亚,色雷斯和东部三个管区还有3支扈从军,这三支军队被算作野战军。也各有一名大元帅统领, 也直接对皇帝本人负责。[125]

帝国东部有13个边区督军直接向他们所在管区所在的大元帅负责: 伊利里亚东部(2名督军), 色雷斯管区(2), 本都管区(1), 东方管区(6)和埃及管区(2).[82][125][126][127]

百官志所呈现的东帝国的军队结构直到查士丁尼统治时期 (525-565年间在位)基本保持不变。[1]

帝国西部的指挥结构

对帝国西部的军队结构的记载的完成时间要远晚于帝国东部。大概425年的时候,西部大多地区失陷于日耳曼蛮族[128] 然而,西部的部分在约400-425年间出现了多次修改:例如,不列颠的军队部署应该是在410年之前,因为罗马军队就是在那个时候明确从不列颠撤出的。[124]这反映了当时的混乱,军队和指挥官的部署不断地变化,反映出了当时的需要。Heather对帝国西部军队中各单位的分析,就说明了这一时期混乱的规模。425年存在的181个扈从军的军团里,只有84个在395年之前就存在,许多 扈从军的军团也仅仅是升级的边防军单位,在395-425的30年间有76个军团在这段时间被解散,[129]直到460年,西部军队几乎完全解体。

因此,百官志所记载的395年的西部部分并不能准确地代表西部军队的结构(相比而言东部的军事指挥体系更为准确)。

西部结构与东部大不相同。在帝国西部,395年之后,皇帝没有办法直接指挥驻扎在各个管区的扈从军的长官,这些长官们则向类似于日本幕府的将军)述职。 这种不正常的结构是由于半汪达尔血统的军事强人斯提里科(395–408掌控国政)造成的,他是狄奥多西指派作为他的儿子霍诺留的监护人,后来霍诺留继任罗马西部的皇帝。在斯提里科在408年死后,接连不断的弱小皇帝确保了这一职位的存在,成为了斯提里科的后继者的专用职位(尤其是埃提乌斯和李希梅尔),直到476年帝国西部彻底解体为止。[130] 这个大元帅的位置一般被叫做两军大元帅 (简称为MVM, 名义上便是"两军之长官",两军则指的是骑兵和步兵). 他直接指挥着驻扎在米兰附近的单一且规模庞大的帝国西部的中央扈从军。

隶属于两军大元帅的是地方的野战军司令,他们都统领着这些地区的驻军: 高卢,不列颠,西伊利里亚,阿非利加,廷吉塔纳(今北非摩洛哥丹吉尔地区)和西班牙。与他们在东部同行不同的是, 东部的同行被称为各管区的 大元帅,西部管区的扈从军的长官都被任命为低一层级的野战军司令,只有高卢地区的高卢骑兵元帅是例外。这大概是因为除了高卢管区的扈从军之外,其余的野战军司令所指挥的士兵数目都远小于 大元帅所理应有的20,000–30,000人的规模。

根据百官志的记载, 全部的12名在西部的督军中有两位督军直接对两军大元帅而非他们所在区域的野战军司令负责。[124][131] 这与东方的情况不一致,可能也不能反映395年的情况。

御林军

无论帝国的东西政府,御林军通常都作为皇帝护卫骑兵部队,游离于军队指挥系统之外。根据百官志的说法,御林军的指挥官保民官通常都对民政部门首脑国务总理大臣直接负责。[132] 但这可能只是出于行政目的。在作战时,御林军保民官 直接向皇帝本人报告。[73]

军队驻地

野战军和边防军的部队对他们的驻扎地有不同的安排。野战军队的部队经常驻扎在市井居民区,而边防军的部队则有固定基地。

大多数边防军都驻留在元首制时期的军团和辅助单位所驻扎的基地[133]一些编制较大的边防军单位(军团和布旗队)驻扎于城市,可能会有永久性的营房。[134] 由于边防军在同一个地区活动,有自己的营地,而且往往从同一地区招募,因此他们往往与当地人保持较好的关系,这与经常被调往其他地区的野战军和中央军不同, 他们经常被安置在平民家中。[135][136]

野战的部队,包括中央军,野战军,有时甚至是伪野战军,通常宿于非战区的城市内,在战时则宿于临时营地。但通常不会像边防军那样在单个城市内的永久基地长期驻扎。从法律证据上看,他们通常被强制性地安置在私人住宅中 (hospitalitas).[137] 这是因为他们经常在不同的省份过冬。常备扈从军陪着皇帝四处征战, 而地区的扈从军 则根据作战需求改变驻扎地。然而在五世纪时期皇帝鲜少直接参与战事,因此在冬季常备常备扈从军的冬季基地变得更加固定。[138] 西部的常备扈从军通常驻扎在Mediolanum (米兰)而东部的两支常备扈从军驻扎在君士坦丁堡附近。[138]

军团的变革

四世纪时期对于军队建制最大的改变就是减少了单一单位的规模而增加了单位的数量,比起过去的军团/辅助军的二元制度而言增加了新的建制类型和等级使得这一系统更为复杂。[139]

军事单位的建制规模

古典晚期的帝国军队单位兵力的相关史料非常零散,而且模棱两可[140] 下表按单位类型和等级给出了一些单位兵力估计:

| 骑兵 单位 |

野战军 (包括中央军) |

边防军 | XXXXX | 步兵 单位 |

野战军 (包括中央军) |

边防军 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 骑兵大队 | 120–500 | 辅助步兵团 | 400–1,200 | |||

| 骑兵连 | 200–300 | 步兵大队 | 160–500 | |||

| 骑兵队 | 80–300 | 军团 | 800–1,200 | 500–1,000 | ||

| 教导团* | 500 | 步兵队 | 200–300 | |||

| 布旗队** | 400–600 | 步兵团 | 200–300 |

*教导团 不适用于 野战军编制,他是御林军的编制

** 布旗队有时也被叫做"骑兵队",比如说斯塔布勒希亚尼骑兵队

很多不确定因素仍然存在,特别是关于边防军军团的编制,其基础编制规模的估算上下差非常大.在4世纪的过程中,单位兵力也有可能发生变化。例如,瓦伦提尼安一世似乎与他的兄弟和共治皇帝瓦伦斯一起拆分了大约150个扈从军单位。由此产生的部队可能只有母部队的一半兵力(除非举行了一次大规模的征兵活动,使他们全部达到原来的兵力)。[140]

教导团根据六世纪的参考资料,其编制在500人左右。[67]

在扈从军中,人们一致认为布旗队的规模在500人左右,而军团则为1000人. 最大的不确定因素是最初由君士坦丁组建的辅助宫廷卫军编制。相关史料是矛盾的,表明这些部队可能是约500人,也可能是约1000人,或者介于两者之间。[142][143] 如果较高的1000人的规模是真的,那么辅助步兵团和军团就别无二致,这是支持辅助步兵团为500人最有力的论据。

For the size of limitanei units, opinion is divided. Jones and Elton suggest from the scarce and ambiguous literary evidence that border legiones numbered c. 1,000 men and that the other units contained in the region of 500 men each.[89][144] Others draw on papyrus and more recent archaeological evidence to argue that limitanei units probably averaged about half the Jones/Elton strength i.e. c. 500 for legiones and around 250 for other units.[76][145]

Unit types

Scholae

Despite existing from the early 4th century, the only full list of scholae available is in the Notitia, which shows the position at the end of the 4th century/early 5th century. At that time, there were 12 scholae, of which 5 were assigned to the Western emperor and 7 to the Eastern. These regiments of imperial escort cavalry would have totalled c. 6,000 men, compared to 2,000 equites singulares Augusti in the late 2nd century.[12] The great majority (10) of the scholae were "conventional" cavalry, armoured in a manner similar to the alae of the Principate, carrying the titles scutarii ("shield-men"), armaturae ("armour" or "harnesses") or gentiles ("natives"). These terms appear to have become purely honorific, although they may originally have denoted special equipment or ethnic composition (gentiles were barbarian tribesmen admitted to the empire on a condition of military service). Only two scholae, both in the East, were specialised units: a schola of clibanarii (cataphracts, or heavily armoured cavalry), and a unit of mounted archers (sagittarii).[146][147] 40 select troops from the scholae, called candidati from their white uniforms, acted as the emperor's personal bodyguards.[73]

Palatini and Comitatenses

In the field armies, cavalry units were known as vexillationes palatini and vex. comitatenses; infantry units as either legiones palatini, auxilia palatini, leg. comitatenses, and pseudocomitatenses.[98][148] Auxilia were only graded as palatini, emphasising their elite status, while the legiones are graded either palatini or comitatenses.[124]

The majority of Roman cavalry regiments in the comitatus (61%) remained of the traditional semi-armoured type, similar in equipment and tactical role to the alae of the Principate and suitable for mêlée combat. These regiments carry a variety of titles: comites, equites scutarii, equites stablesiani or equites promoti. Again, these titles are probably purely traditional, and do not indicate different unit types or functions.[20] 24% of regiments were unarmoured light cavalry, denoted equites Dalmatae, equites Mauri or equites sagittarii (mounted archers), suitable for harassment and pursuit. Mauri light horse had served Rome as auxiliaries since the Second Punic War 500 years before. Equites Dalmatae, on the other hand, seem to have been regiments first raised in the 3rd century. 15% of comitatus cavalry regiments were heavily armoured cataphractarii or clibanarii, which were suitable for the shock charge (all but one such squadrons are listed as comitatus regiments by the Notitia)[149]

Infantry units mostly fought in close order as did their forebears from the Principate. Infantry equipment was broadly similar to that of auxiliaries in the 2nd century, with some modifications (see Equipment, below).[20]

Limitanei

In the limitanei, most types of unit were present. Infantry units include milites, numeri and auxilia as well as old-style legiones and cohortes. Cavalry units include equites, cunei and old-style alae.[144]

The evidence is that units of the comitatenses were believed to be higher quality than of the limitanei. But the difference should not be exaggerated. Suggestions have been made that the limitanei were a part-time militia of local farmers, of poor combat capability.[150] This view is rejected by many modern scholars.[144][151][152] The evidence is that limitanei were full-time professionals.[153] They were charged with combating the incessant small-scale barbarian raids that were the empire's enduring security problem.[154] It is therefore likely that their combat readiness and experience were high. This was demonstrated at the siege of Amida (359) where the besieged frontier legions resisted the Persians with great skill and tenacity.[155] Elton suggests that the lack of mention in the sources of barbarian incursions less than 400-strong implies that such were routinely dealt with by the border forces without the need of assistance from the comitatus.[156] Limitanei regiments often joined the comitatus for specific campaigns, and were sometimes retained by the comitatus long-term with the title of pseudocomitatenses, implying adequate combat capability.[153]

Specialists

| 外部圖片链接 | |

|---|---|

The late Roman army contained a significant number of heavily armoured cavalry called cataphractarii (from the Greek kataphraktos, meaning "covered all over"). They were covered from neck to foot by a combination of scale and/or lamellar armour for the torso and laminated defences for the limbs (see manica), and their horses were often armoured also. Cataphracts carried a long, heavy lance called a contus, c. 3.65米(12英尺) long, that was held in both hands. Some also carried bows.[158] The central tactic of cataphracts was the shock charge, which aimed to break the enemy line by concentrating overwhelming force on a defined section of it. A type of cataphract called a clibanarius also appears in the 4th-century record. This term may be derived from Greek klibanos (a bread oven) or from a Persian word. It is likely that clibanarius is simply an alternative term to cataphract, or it may have been a special type of cataphract.[20] This type of cavalry had been developed by the Iranian horse-based nomadic tribes of the Eurasian steppes from the 6th century BC onwards: the Scythians and their kinsmen the Sarmatians. The type was adopted by the Parthians in the 1st century BC and later by the Romans, who needed it to counter Parthians in the East and the Sarmatians along the Danube.[159] The first regiment of Roman cataphracts to appear in the archaeological record is the ala I Gallorum et Pannoniorum cataphractaria, attested in Pannonia in the early 2nd century.[160] Although Roman cataphracts were not new, they were far more numerous in the late army, with most regiments stationed in the East.[161] However, several of the regiments placed in the Eastern army had Gaulish names, indicating an ultimately Western origin.[162]

Archer units are denoted in the Notitia by the term equites sagittarii (mounted archers) and sagittarii (foot archers, from sagitta = "arrow"). As in the Principate, it is likely that many non-sagittarii regiments also contained some archers. Mounted archers appear to have been exclusively in light cavalry units.[20] Archer units, both foot and mounted, were present in the comitatus.[163] In the border forces, only mounted archers are listed in the Notitia, which may indicate that many limitanei infantry regiments contained their own archers.[164]

A distinctive feature of the late army is the appearance of independent units of artillery, which during the Principate appears to have been integral to the legions. Called ballistarii (from ballista = "catapult"), 7 such units are listed in the Notitia, all but one belonging to the comitatus. But a number are denoted pseudocomitatenses, implying that they originally belonged to the border forces. The purpose of independent artillery units was presumably to permit heavy concentration of firepower, especially useful for sieges. However, it is likely that many ordinary regiments continued to possess integral artillery, especially in the border forces.[165]

The Notitia lists a few units of presumably light infantry with names denoting specialist function: superventores and praeventores ("interceptors") exculcatores ("trackers"), exploratores ("scouts").[166] At the same time, Ammianus describes light-armed troops with various terms: velites, leves armaturae, exculcatores, expediti. It is unclear from the context whether any of these were independent units, specialist sub-units, or indeed just detachments of ordinary troops specially armed for a particular operation.[167] The Notitia evidence implies that, at least in some cases, Ammianus could be referring to independent units.

Bucellarii

Bucellarii (the Latin plural of bucellarius; literally "biscuit–eater",[168] 希臘語:βουκελλάριοι) is a term for professional soldiers in the late Roman and Byzantine Empire, who were not supported directly by the state but rather by an individual, though they also took an oath of obedience to the reigning emperor. The employers of these "household troops" were usually prominent generals or high ranking civilian bureaucrats. Units of these troops were generally quite small, but, especially during the many civil wars, they could grow to number several thousand men. In effect, the bucellarii were small private armies equipped and paid by wealthy and influential people. As such they were quite often better trained and equipped, not to mention motivated, than the regular soldiers of the time. Originating in the late fourth century, they increased in importance until, in the early Byzantine army, they could form major elements of expeditionary armies. Notable employers of bucellarii included the magistri militiae Stilicho and Aetius, and the Praetorian Prefect Rufinus.[169]

Foederati

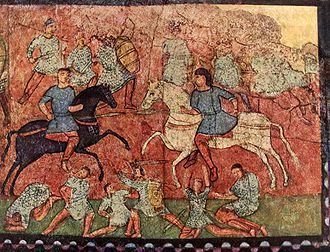

Outside the regular army were substantial numbers of allied forces, generally known as foederati (from foedus = "treaty") or symmachi in the East. The latter were forces supplied either by barbarian chiefs under their treaty of alliance with Rome or dediticii.[170] Such forces were employed by the Romans throughout imperial history e.g. the battle scenes from Trajan's Column in Rome show that foederati troops played an important part in the Dacian Wars (101–6).[171]

In the 4th century, as during the Principate, these forces were organised into ill-defined units based on a single ethnic group called numeri ("troops", although numerus was also the name of a regular infantry unit).[172] They served alongside the regular army for the duration of particular campaigns or for a specified period. Normally their service would be limited to the region where the tribe lived, but sometimes could be deployed elsewhere.[173] They were commanded by their own leaders. It is unclear whether they used their own weapons and armour or the standard equipment of the Roman army. In the late army, the more useful and long-serving numeri appear to have been absorbed into the regular late army, rapidly becoming indistinguishable from other units.[174]

Recruitment

Romans

During the Principate, it appears that most recruits, both legionary and auxiliary, were volunteers (voluntarii). Compulsory conscription (dilectus) was never wholly abandoned, but was generally only used in emergencies or before major campaigns when large numbers of additional troops were required.[175] In marked contrast, the late army relied mainly on compulsion for its recruitment of Roman citizens. Firstly, the sons of serving soldiers or veterans were required by law to enlist. Secondly, a regular annual levy was held based on the indictio (land tax assessment). Depending on the amount of land tax due on his estates, a landowner (or group of landowners) would be required to provide a commensurate number of recruits to the army. Naturally, landowners had a strong incentive to keep their best young men to work on their estates, sending the less fit or reliable for military service. There is also evidence that they tried to cheat the draft by offering the sons of soldiers (who were liable to serve anyway) and vagrants (vagi) to fulfil their quota.[47]

However, conscription was not in practice universal. Firstly, a land-based levy meant recruits were exclusively the sons of peasants, as opposed to townspeople.[47] Thus some 20% of the empire's population was excluded.[176] In addition, as during the Principate, slaves were not admissible. Nor were freedmen and persons in certain occupations such as bakers and innkeepers. In addition, provincial officials and curiales (city council members) could not enlist. These rules were relaxed only in emergencies, as during the military crisis of 405–6 (Radagaisus' invasion of Italy and the great barbarian invasion of Gaul).[177] Most importantly, the conscription requirement was often commuted into a cash levy, at a fixed rate per recruit due. This was done for certain provinces, in certain years, although the specific details are largely unknown. It appears from the very slim available evidence that conscription was not applied evenly across provinces but concentrated heavily in the army's traditional recruiting areas of Gaul (including the two Germaniae provinces along the Rhine) and the Danubian provinces, with other regions presumably often commuted. An analysis of the known origins of comitatenses in the period 350–476 shows that in the Western army, the Illyricum and Gaul dioceses together provided 52% of total recruits. Overall, the Danubian regions provided nearly half of the whole army's recruits, despite containing only three of the 12 dioceses.[178] This picture is much in line with the 2nd-century position.[179]

Prospective recruits had to undergo an examination. Recruits had to be 20–25 years of age, a range that was extended to 19–35 in the later 4th century. Recruits had to be physically fit and meet the traditional minimum height requirement of 6 Roman feet (5 ft 10in, 178 cm) until 367, when it was reduced to 5 Roman feet and 3 Roman palms (5 ft 7in, 170 cm).[180] Vegetius hints that in the very late Empire (ca. AD 400) even this height requirement may have been relaxed, for "... if necessity demands, it is right to take account not so much of stature as of strength. Even Homer himself is not wanting as a witness, since he records that Tydeus was small in body but a strong warrior".[181]

Once a recruit was accepted he was 'marked' on the arm, presumably a tattoo or brand, to facilitate recognition if he attempted to desert.[182] The recruit was then issued with an identification disk (which was worn around the neck) and a certificate of enlistment (probatoria). He was then assigned to a unit. A law of 375 required those with superior fitness to be assigned to the comitatenses.[183] In the 4th century, the minimum length of service was 20 years (24 years in some limitanei units).[184] This compares with 25 years in both legions and auxilia during the Principate.

The widespread use of conscription, the compulsory recruitment of soldiers' sons, the relaxation of age and height requirements and the branding of recruits all add up to a picture of an army that had severe difficulties in finding, and retaining, sufficient recruits.[185] Recruitment difficulties are confirmed in the legal code evidence: there are measures to deal with cases of self-mutilation to avoid military service (such as cutting off a thumb), including an extreme decree of 386 requiring such persons to be burnt alive.[184] Desertion was clearly a serious problem, and was probably much worse than in the army of the Principate, since the latter was mainly a volunteer army. This is supported by the fact that the granting of leave of absence (commeatus) was more strictly regulated. While in the 2nd century, a soldier's leave was granted at the discretion of his regimental commander, in the 4th century, leave could only be granted by a far senior officer (dux, comes or magister militum).[186][187] In addition, it appears that comitatus units were typically one-third understrength.[98] The massive disparity between official and actual strength is powerful evidence of recruitment problems. Against this, Elton argues that the late army did not have serious recruitment problems, on the basis of the large numbers of exemptions from conscription that were granted.[188]

Barbarians

Barbari ("barbarians") was the generic term used by the Romans to denote peoples resident beyond the borders of the empire, and best translates as "foreigners" (it is derived from a Greek word meaning "to babble": a reference to their incomprehensible languages).

Most scholars believe that significant numbers of barbari were recruited throughout the Principate by the auxilia (the legions were closed to non-citizens).[184][189] However, there is little evidence of this before the 3rd century. The scant evidence suggests that the vast majority, if not all, of auxilia were Roman peregrini (second-class citizens) or Roman citizens.[190] In any case, the 4th-century army was probably much more dependent on barbarian recruitment than its 1st/2nd-century predecessor. The evidence for this may be summarised as follows:

- The Notitia lists a number of barbarian military settlements in the empire. Known as laeti or gentiles ("natives"), these were an important source of recruits for the army. Groups of Germanic or Sarmatian tribespeople were granted land to settle in the Empire, in return for military service. Most likely each community was under a treaty obligation to supply a specified number of troops to the army each year.[184] The resettlement within the empire of barbarian tribespeople in return for military service was not a new phenomenon in the 4th century: it stretches back to the days of Augustus.[191] But it does appear that the establishment of military settlements was more systematic and on a much larger scale in the 4th century.[192]

- The Notitia lists a large number of units with barbarian names. This was probably the result of the transformation of irregular allied units serving under their own native officers (known as socii, or foederati) into regular formations. During the Principate, regular units with barbarian names are not attested until the 3rd century and even then rarely e.g. the ala I Sarmatarum attested in 3rd-century Britain, doubtless an offshoot of the Sarmatian horsemen posted there in 175.[193]

- The emergence of significant numbers of senior officers with barbarian names in the regular army, and eventually in the high command itself. In the early 5th century, the Western Roman forces were often controlled by barbarian-born generals or generals with some barbarian ancestry, such as Arbogast, Stilicho and Ricimer.[194]

- The adoption by the 4th-century army of barbarian (especially Germanic) dress, customs and culture, suggesting enhanced barbarian influence. For example, Roman army units adopted mock barbarian names e.g. Cornuti = "horned ones", a reference to the German custom of attaching horns to their helmets, and the barritus, a German warcry. Long hair became fashionable, especially in the palatini regiments, where barbarian-born recruits were numerous.[195]

Quantification of the proportion of barbarian-born troops in the 4th-century army is highly speculative. Elton has undertaken the most detailed analysis of the meagre evidence. According to this analysis, about a quarter of the sample of army officers was barbarian-born in the period 350–400. Analysis by decade shows that this proportion did not increase over the period, or indeed in the early 5th century. The latter trend implies that the proportion of barbarians in the lower ranks was not much greater, otherwise the proportion of barbarian officers would have increased over time to reflect that.[196]

If the proportion of barbarians was in the region of 25%, then it is probably much higher than in the 2nd-century regular army. If the same proportion had been recruited into the auxilia of the 2nd-century army, then in excess of 40% of recruits would have been barbarian-born, since the auxilia constituted 60% of the regular land army.[11] There is no evidence that recruitment of barbarians was on such a large scale in the 2nd century.[36] An analysis of named soldiers of non-Roman origin shows that 75% were Germanic: Franks, Alamanni, Saxons, Goths, and Vandals are attested in the Notitia unit names.[197] Other significant sources of recruits were the Sarmatians from the Danubian lands; and Armenians and Iberians from the Caucasus region.[198]

In contrast to Roman recruits, the vast majority of barbarian recruits were probably volunteers, drawn by conditions of service and career prospects that to them probably appeared desirable, in contrast to their living conditions at home. A minority of barbarian recruits were enlisted by compulsion, namely dediticii (barbarians who surrendered to the Roman authorities, often to escape strife with neighbouring tribes) and tribes who were defeated by the Romans, and obliged, as a condition of peace, to undertake to provide a specified number of recruits annually. Barbarians could be recruited directly, as individuals enrolled into regular regiments, or indirectly, as members of irregular foederati units transformed into regular regiments.[199]

Ranks, pay and benefits

Common soldiers

At the base of the rank pyramid were the common soldiers: pedes (infantryman) and eques (cavalryman). Unlike his 2nd-century counterpart, the 4th-century soldier's food and equipment was not deducted from his salary (stipendium), but was provided free.[200] This is because the stipendium, paid in debased silver denarii, was under Diocletian worth far less than in the 2nd century. It lost its residual value under Constantine and ceased to be paid regularly in mid-4th century.[201]

The soldier's sole substantial disposable income came from the donativa, or cash bonuses handed out periodically by the emperors, as these were paid in gold solidi (which were never debased), or in pure silver. There was a regular donative of 5 solidi every five years of an Augustus reign (i.e. one solidus p.a.) Also, on the accession of a new Augustus, 5 solidi plus a pound of silver (worth 4 solidi, totaling 9 solidi) were paid. The 12 Augusti that ruled the West between 284 and 395 averaged about nine years per reign. Thus the accession donatives would have averaged about 1 solidus p.a. The late soldier's disposable income would thus have averaged at least 2 solidi per annum. It is also possible, but undocumented, that the accession bonus was paid for each Augustus and/or a bonus for each Caesar.[202] The documented income of 2 solidi was only a quarter of the disposable income of a 2nd-century legionary (which was the equivalent of c. 8 solidi).[203] The late soldier's discharge package (which included a small plot of land) was also minuscule compared with a 2nd-century legionary's, worth just a tenth of the latter's.[204][205]

Despite the disparity with the Principate, Jones and Elton argue that 4th-century remuneration was attractive compared to the hard reality of existence at subsistence level that most recruits' peasant families had to endure.[206] Against that has to be set the clear unpopularity of military service.

However, pay would have been much more attractive in higher-grade units. The top of the pay pyramid were the scholae elite cavalry regiments. Next came palatini units, then comitatenses, and finally limitanei. There is little evidence about the pay differentials between grades. But that they were substantial is shown by the example that an actuarius (quartermaster) of a comitatus regiment was paid 50% more than his counterpart in a pseudocomitatensis regiment.[207]

Regimental officers

Regimental officer grades in old-style units (legiones, alae and cohortes) remained the same as under the Principate up to and including centurion and decurion. In the new-style units, (vexillationes, auxilia, etc.), ranks with quite different names are attested, seemingly modelled on the titles of local authority bureaucrats.[208] So little is known about these ranks that it is impossible to equate them with the traditional ranks with any certainty. Vegetius states that the ducenarius commanded, as the name implies, 200 men. If so, the centenarius may have been the equivalent of a centurion in the old-style units.[209] Probably the most accurate comparison is by known pay levels:

| Multiple of basic pay (2nd century) or annona (4th century) |

2nd-century cohors (ascending ranks) |

4th-century units (ascending ranks) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | pedes (infantryman) | pedes |

| 1.5 | tesserarius ("corporal") | semissalis |

| 2 | signifer (centuria standard-bearer) optio (centurion's deputy) vexillarius (cohort standard-bearer) |

circitor biarchus |

| 2.5 to 5 | centenarius (2.5) ducenarius (3.5) senator (4) primicerius (5) | |

| Over 5 | centurio (centurion) centurio princeps (chief centurion) beneficiarius? (deputy cohort commander) |

NOTE: Ranks correspond only in pay scale, not necessarily in function

The table shows that the pay differentials enyjoyed by the senior officers of a 4th-century regiment were much smaller than those of their 2nd-century counterparts, a position in line with the smaller remuneration enjoyed by 4th-century high administrative officials.

Regimental and corps commanders

| Pay scale (multiple of pedes) |

Rank (ascending order) |

No. of posts (Notitia) |

Job description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Protector | Several hundreds (200 in domestici under Julian) |

cadet regimental commander |

| n.a. | Tribunus (or praefectus) | c. 800 | regimental commander |

| n.a. | Tribunus comes | n.a. | (i) commander, protectores domestici (comes domesticorum) (ii) commander, brigade of two twinned regiments or (iii) some (later all) tribuni of scholae (iv) some staff officers (tribuni vacantes) to magister or emperor |

| 100 | Dux (or, rarely, comes) limitis | 27 | border army commander |

| n.a. | Comes rei militaris | 7 | (i) commander, smaller diocesan comitatus |

| n.a. | Magister militum (magister equitum in West) |

4 | commander, larger diocesan comitatus |

| n.a. | Magister militum praesentalis (magister utriusque militiae in West) |

3 | commander, comitatus praesentalis |

The table above indicates the ranks of officers who held a commission (sacra epistula, lit: "solemn letter"). This was presented to the recipient by the emperor in person at a dedicated ceremony.[212]

Cadet regimental commanders (protectores)

A significant innovation of the 4th century was the corps of protectores, which contained cadet senior officers. Although protectores were supposed to be soldiers who had risen through the ranks by meritorious service, it became a widespread practice to admit to the corps young men from outside the army (often the sons of senior officers). The protectores formed a corps that was both an officer training-school and pool of staff officers available to carry out special tasks for the magistri militum or the emperor. Those attached to the emperor were known as protectores domestici and organised in four scholae under a comes domesticorum. After a few years' service in the corps, a protector would normally be granted a commission by the emperor and placed in command of a military regiment.[214]

Regimental commanders (tribuni)

Regimental commanders were known by one of three possible titles: tribunus (for comitatus regiments plus border cohortes), praefectus (most other limitanei regiments) or praepositus (for milites and some ethnic allied units).[215][216] However, tribunus was used colloquially to denote the commander of any regiment. Although most tribuni were appointed from the corps of protectores, a minority, again mainly the sons of high-ranking serving officers, were directly commissioned outsiders.[217] The status of regimental commanders varied enormously depending on the grade of their unit. At the top end, some commanders of scholae were granted the noble title of comes, a practice which became standard after 400.[218]

Senior regimental commanders (tribuni comites)

The comitiva or "Order of Companions (of the emperor)", was an order of nobility established by Constantine I to honour senior administrative and military officials, especially in the imperial entourage. It partly overlapped with the established orders of Senators and of Knights, in that it could be awarded to members of either (or of neither). It was divided into three grades, of which only the first, comes primi ordinis (lit. "Companion of the First Rank", which carried senatorial rank), retained any value beyond AD 450, due to excessive grant. In many cases, the title was granted ex officio, but it could also be purely honorary.[219]

In the military sphere, the title of comes primi ordinis was granted to a group of senior tribuni. These included (1) the commander of the protectores domestici, who by 350 was known as the comes domesticorum;[220] (2) some tribuni of scholae: after c. 400, scholae commanders were routinely granted the title on appointment;[221] (3) the commanders of a brigade of two twinned comitatus regiments were apparently styled comites. (Such twinned regiments would always operate and transfer together e.g. the legions Ioviani and Herculiani);[222] (4) finally, some tribunes without a regimental command (tribuni vacantes), who served as staff-officers to the emperor or to a magister militum, might be granted the title.[221] These officers were not equal in military rank with a comes rei militaris, who was a corps commander (usually of a smaller diocesan comitatus), rather than the commander of only one or two regiments (or none).

Corps commanders (duces, comites rei militaris, magistri militum)

The commanders of army corps, i.e. army groups composed of several regiments, were known as (in ascending order of rank): duces limitis, comites rei militaris, and magistri militum. These officers corresponded in rank to generals and field marshals in modern armies.

A Dux (or, rarely, comes) limitis (lit. "Border Leader"), was in command of the troops (limitanei), and fluvial flotillas, deployed in a border province. Until the time of Constantine I, the dux reported to the vicarius of the diocese in which their forces were deployed. After c. 360, the duces generally reported to the commander of the comitatus deployed in their diocese (whether a magister militum or comes).[72] However, they were entitled to correspond directly with the emperor, as various imperial rescripts show. A few border commanders were, exceptionally, styled comes e.g. the comes litoris Saxonici ("Count of the Saxon Shore") in Britain.[223]

A Comes rei militaris (lit. "Companion for Military Affairs") was generally in command of a smaller diocesan comitatus (typically ca. 10,000 strong). By the time of the Notitia, comites were mainly found in the West, because of the fragmentation of the western comitatus into a number of smaller groups. In the East, there were 2 comites rei militaris, in command of Egypt and Isauria. Exceptionally, these men were in command of limitanei regiments only. Their title may be due to the fact that they reported, at the time to the Notitia, to the emperor direct (later they reported to the magister militum per Orientem).[124] A comes rei militaris also had command over the border duces in his diocese.

A Magister militum (lit. "Master of Soldiers") commanded the larger diocesan comitatus (normally over 20,000-strong). A magister militum was also in command of the duces in the diocese where his comitatus was deployed.

The highest rank of Magister militum praesentalis (lit. "Master of Soldiers in the Presence [of the Emperor]") was accorded to the commanders of imperial escort armies (typically 20-30,000 strong). The title was equivalent in rank to Magister utriusque militiae ("Master of Both Services"), Magister equitum ("Master of Cavalry") and Magister peditum ("Master of Infantry").

It is unknown what proportion of the corps commanders had risen from the ranks, but it is likely to have been small as most rankers would be nearing retirement age by the time they were given command of a regiment and would be promoted no further.[224] In contrast, directly commissioned protectores and tribuni dominated the higher echelons, as they were usually young men when they started. For such men, promotion to corps command could be swift e.g. the future emperor Theodosius I was a dux at age 28.[225] It was also possible for rungs on the rank-ladder to be skipped. Commanders of scholae, who enjoyed direct access to the emperor, often reached the highest rank of magister militum: e.g. the barbarian-born officer Agilo was promoted direct to magister militum from tribunus of a schola in 360, skipping the dux stage.[221]

Equipment

The basic equipment of a 4th-century foot soldier was essentially the same as in the 2nd century: metal armour cuirass, metal helmet, shield and sword.[226] Some evolution took place during the 3rd century. Trends included the adoption of warmer clothing; the disappearance of distinctive legionary armour and weapons; the adoption by the infantry of equipment used by the cavalry in the earlier period; and the greater use of heavily armoured cavalry called cataphracts.

Clothing

In the 1st and 2nd centuries, a Roman soldier's clothes consisted of a single-piece, short-sleeved tunic the hem of which reached the knees and special hobnailed sandals (caligae). This attire, which left the arms and legs bare, had evolved in a Mediterranean climate and was not suitable for northern Europe in cold weather. In northern Europe, long-sleeved tunics, trousers (bracae), socks (worn inside the caligae) and laced boots were commonly worn in winter from the 1st century. During the 3rd century, these items of clothing became much more widespread, apparently common in Mediterranean provinces also.[227] However, it is likely that in warmer weather, trousers were dispensed with and caligae worn instead of socks and boots.[228] Late Roman clothing was often highly decorated, with woven or embroidered strips, clavi, circular roundels, orbiculi, or square panels, tabulae, added to tunics and cloaks. These colourful decorative elements usually consisted of geometrical patterns and stylised plant motifs, but could include human or animal figures.[229] A distinctive part of a soldier's costume, though it seems to have also been worn by non-military bureaucrats, was a type of round, brimless hat known as the pannonian cap (pileus pannonicus).[230]

Armour

Legionary soldiers of the 1st and 2nd centuries had use of the lorica segmentata, or laminated-strip cuirass, as well as mail (lorica hamata) and scale armour (lorica squamata). Testing of modern copies have demonstrated that segmentata was impenetrable to most direct and missile strikes. It was, however, uncomfortable: reenactors have discovered that chafing renders it painful to wear for longer than a few hours at a time, and it was also expensive to produce and difficult to maintain.[231] In the 3rd century, the segmentata appears to have fallen out of use and troops were depicted wearing mail or scale.

In either the 390s[232] or the 430s[233][234]), Vegetius reports that soldiers no longer wore armour:

From the foundation of the city till the reign of the Emperor Gratian, the foot wore cuirasses and helmets. But negligence and sloth having by degrees introduced a total relaxation of discipline, the soldiers began to think their armor too heavy, as they seldom put it on. They first requested leave from the Emperor to lay aside the cuirass and afterwards the helmet. In consequence of this, our troops in their engagements with the Goths were often overwhelmed with their showers of arrows. Nor was the necessity of obliging the infantry to resume their cuirasses and helmets discovered, notwithstanding such repeated defeats, which brought on the destruction of so many great cities. Troops, defenseless and exposed to all the weapons of the enemy, are more disposed to fly than fight. What can be expected from a foot-archer without cuirass or helmet, who cannot hold at once his bow and shield; or from the ensigns whose bodies are naked, and who cannot at the same time carry a shield and the colors? The foot soldier finds the weight of a cuirass and even of a helmet intolerable. This is because he is so seldom exercised and rarely puts them on.[235]

It is possible that Vegetius' statements about the abandonment of armour were a misinterpretation by him of sources mentioning Roman soldiers fighting without armour in more open formations during the Gothic wars of the 370s.[236] Evidence that armour continued to be worn by Roman soldiers, including infantry, throughout the period is widespread.[237]

The artistic record shows most late Roman soldiers wearing metal armour. For example, illustrations in the Notitia Dignitatum, compiled after the reign of Gratian, indicate that the army's fabricae (arms factories) were producing mail armour at the end of the 4th century.[238] The Vatican Virgil manuscript, early 5th century, and the Column of Arcadius, reigned 395 to 408, both show armoured soldiers.[239] Actual examples of quite large sections of mail have been recovered, at Trier (with a section of scale), Independența, and Weiler-la-Tour, within a late 4th-century context.[240] Officers and some soldiers may have worn muscle cuirasses, together with decorative pteruges.[241] In contrast to the earlier segmentata plate armour, which afforded no protection for the arms or below the hips, some pictorial and sculptural representations of Late Roman soldiers show mail or scale armours giving more extensive protection. These armours had full-length sleeves and were long enough to protect the thighs.[242]

The catafractarii and clibanarii cavalry, from limited pictorial evidence and especially from the description of these troops by Ammianus, may have worn specialised forms of armour. In particular their limbs were protected by laminated defences, made up of curved and overlapping metal segments: "Laminarum circuli tenues apti corporis flexibus ambiebant per omnia membra diducti" (Thin circles of iron plates, fitted to the curves of their bodies, completely covered their limbs).[243] Such laminated defences are attested by a fragment of manica found at Bowes Moor, dating to the late 4th century.[244]

Helmets

In general, Roman cavalry helmets had enhanced protection, in the form of wider cheek-guards and deeper neck-guards, for the sides and back of the head than infantry helmets. Infantry were less vulnerable in those parts due to their tighter formation when fighting.[245] During the 3rd century, infantry helmets tended to adopt the more protective features of Principate cavalry helmets. Cheek-guards could often be fastened together over the chin to protect the face, and covered the ears save for a slit to permit hearing e.g. the "Auxiliary E" type or its Niederbieber variant. Cavalry helmets became even more enclosed e.g. the "Heddernheim" type, which is close to the medieval great helm, but at the cost much reduced vision and hearing.[246]

In the late 3rd century a complete break in Roman helmet design occurred. Previous Roman helmet types, based ultimately on Celtic designs, were replaced by new forms derived from helmets developed in the Sassanid Empire. The new helmet types were characterised by a skull constructed from multiple elements united by a medial ridge, and are referred to as "ridge helmets". They are divided into two sub-groups, the "Intercisa" and "Berkasovo" types.[247] The "Intercisa" design had a two-piece skull, it left the face unobstructed and had ear-holes in the join between the small cheek-guards and bowl to allow good hearing. It was simpler and cheaper to manufacture, and therefore probably by far the most common type, but structurally weaker and therefore offered less effective protection.[248] The "Berkasovo" type was a more sturdy and protective ridge helmet. This type of helmet usually has 4 to 6 skull elements (and the characteristic median ridge), a nasal (nose-guard), a deep brow piece riveted inside the skull elements and large cheekpieces. Unusually the helmet discovered at Burgh Castle, in England, is of the Berkasovo method of construction, but has cheekpieces with earholes. Face-guards of mail or in the form of metal 'anthropomorphic masks' with eye-holes were often added to the helmets of the heaviest forms of cavalry, especially catafractarii or clibanarii.[249][250]

Despite the apparent cheapness of manufacture of their basic components, many surviving examples of Late Roman helmets, including the Intercisa type, show evidence of expensive decoration in the form of silver or silver-gilt sheathing.[251][252] A possible explanation is that most of the surviving exemplars may have belonged to officers and that silver- or gold-plating denoted rank; and, in the case of mounted gemstones, high rank.[209] Other academics, in contrast, consider that silver-sheathed helmets may have been widely worn by comitatenses soldiers, given as a form of pay or reward.[253] Roman law indicates that all helmets of this construction were supposed to be sheathed in a specific amount of gold or silver.[254]

Shields

The classic legionary scutum, a convex rectangular shield, also disappeared during the 3rd century. All troops except archers adopted large, wide, usually dished, ovoid (or sometimes round) shields. These shields were still called Scuta or Clipei, despite the difference in shape.[255][256] Shields, from examples found at Dura Europos and Nydam, were of vertical plank construction, the planks glued, and mostly faced inside and out with painted leather. The edges of the shield were bound with stitched rawhide, which shrank as it dried improving structural cohesion.[257]

Hand weapons

The gladius, a short (median length: 460 mm/18 inches) stabbing-sword that was designed for close-quarters fighting, and was standard for the infantry of the Principate (both legionary and auxiliary), also was phased out during the 3rd century. The infantry adopted the spatha, a longer (median length: 760 mm/30 in) sword that during the earlier centuries was used by the cavalry only.[20] In addition, Vegetius mentions the use of a shorter-bladed sword termed a semispatha.[258] At the same time, infantry acquired a thrusting-spear (hasta) which became the main close order combat weapon to replace the gladius. These trends imply a greater emphasis on fighting the enemy "at arm's length".[259] In the 4th century, there is no archaeological or artistic evidence of the pugio (Roman military dagger), which is attested until the 3rd century. 4th-century graves have yielded short, single-edged knives in conjunction with military belt fittings.[260]

Missiles

In addition to his thrusting-spear, a late foot soldier might carry a spiculum, a kind of pilum, similar to an angon. Alternatively, he may have been armed with short javelins (verruta or lanceae). Late Roman infantrymen often carried half a dozen lead-weighted throwing-darts called plumbatae (from plumbum = "lead"), with an effective range of c. 30米(98英尺), well beyond that of a javelin. The darts were carried clipped to the back of the shield or in a quiver.[261] The late foot soldier thus had greater missile capability than his predecessor from the Principate, who was often limited to just two pila.[262] Late Roman archers continued to use the recurved composite bow as their principal weapon. This was a sophisticated, compact and powerful weapon, suitable for mounted and foot archers alike. A small number of archers may have been armed with crossbows (manuballistae).[263]

Supply infrastructure

A critical advantage enjoyed by the late army over all its foreign enemies except the Persians was a highly sophisticated organisation to ensure that the army was properly equipped and supplied on campaign. Like their enemies, the late army could rely on foraging for supplies when campaigning on enemy soil. But this was obviously undesirable on Roman territory and impractical in winter, or in spring before the harvest.[264][265] The empire's complex supply organisation enabled the army to campaign in all seasons and in areas where the enemy employed a "scorched earth" policy.

Supply organisation

The responsibility for supplying the army rested with the praefectus praetorio of the operational sector. He in turn controlled a hierarchy of civilian authorities (diocesan vicarii and provincial governors), whose agents collected, stored and delivered supplies to the troops directly or to predetermined fortified points.[266] The quantities involved were enormous and would require lengthy and elaborate planning for major campaigns. A late legion of 1,000 men would require a minimum of 2.3 tonnes of grain-equivalent every day.[267] An imperial escort army of 25,000 men would thus require around 5,000 tonnes of grain-equivalent for three months' campaigning (plus fodder for the horses and pack animals).

Supply transport

Such vast cargoes would be carried by boat as far as possible, by sea and/or river, and only the shortest possible distance overland. That is because transport on water was far more economical than on land (as it remains today, although the differential is smaller).

Land transport of military supplies on the cursus publicus (imperial transport service) was typically by wagons (angariae), with a maximum legal load of 1,500 lbs (680 kg), drawn by two pairs of oxen.[268] The payload capacity of most Roman freighter-ships of the period was in the range of 10,000–20,000 modii (70–140 tonnes) although many of the grain freighters supplying Rome were much larger up 350 tonnes and a few giants which could load 1200 like the Isis which Lucian saw in Athens circa 180 A.D.[269] Thus, a vessel of median capacity of 100 tonnes, with a 20-man crew, could carry the same load as c. 150 wagons (which required 150 drivers and 600 oxen, plus pay for the former and fodder for the animals). A merchant ship would also, with a favourable wind, typically travel three times faster than the typical 3 km/h(2 mph) achieved by the wagons and for as long as there was daylight, whereas oxen could only haul for at most 5 hours per day. Thus freighters could easily cover 100 km(62 mi) per day, compared to c. 15 km(9 mi) by the wagons.[270][271] Against this must be set the fact that most freighters of this capacity were propelled by square sails only (and no oars). They could only progress if there was a following wind, and could spend many days in port waiting for one. (However, smaller coastal and fluvial freighters called actuariae combined oars with sail and had more flexibility). Maritime transport was also completely suspended for at least four months in the winter (as stormy weather made it too hazardous) and even during the rest of the year, shipwrecks were common.[272] Nevertheless, the surviving shipping-rates show that it was cheaper to transport a cargo of grain by sea from Syria to Lusitania (i.e. the entire length of the Mediterranean – and a ways beyond – c. 5,000 km) than just 110 km(68 mi) overland.[270]

On rivers, actuariae could operate year-round, except during periods when the rivers were ice-bound or of high water (after heavy rains or thaw), when the river-current was dangerously strong. It is likely that the establishment of the empire's frontier on the Rhine-Danube line was dictated by the logistical need for large rivers to accommodate supply ships more than by defensibility. These rivers were dotted with purpose-built military docks (portus exceptionales).[273] The protection of supply convoys on the rivers was the responsibility of the fluvial flotillas (classes) under the command of the riverine duces. The Notitia gives no information about the Rhine flotillas (as the Rhine frontier had collapsed by the time the Western section was compiled), but mentions 4 classes Histricae (Danube flotillas) and 8 other classes in tributaries of the Danube. Each flotilla was commanded by a praefectus classis who reported to the local dux. It appears that each dux on the Danube disposed of at least one flotilla (one, the dux Pannoniae, controlled three).[274]

Weapons manufacture

In the 4th century, the production of weapons and equipment was highly centralised (and presumably standardised) in a number of major state-run arms factories, or fabricae, documented in the Notitia. It is unknown when these were first established, but they certainly existed by the time of Diocletian.[275] In the 2nd century, there is evidence of fabricae inside legionary bases and even in the much smaller auxiliary forts, staffed by the soldiers themselves.[276] But there is no evidence, literary or archaeological, of fabricae outside military bases and staffed by civilians during the Principate (although their existence cannot be excluded, as no archaeological evidence has been found for the late fabricae either). Late fabricae were located in border provinces and dioceses.[277] Some were general manufacturers producing both armour and weapons (fabrica scutaria et armorum) or just one of the two. Others were specialised in one or more of the following: fabrica spatharia (sword manufacture), lanciaria (spears), arcuaria (bows), sagittaria (arrows), loricaria (body armour), clibanaria (cataphract armour), and ballistaria (catapults).[278]

Fortifications

Compared to the 1st and 2nd centuries, the 3rd and 4th centuries saw much greater fortification activity, with many new forts built.[142] Later Roman fortifications, both new and upgraded old ones, contained much stronger defensive features than their earlier counterparts. In addition, the late 3rd/4th centuries saw the fortification of many towns and cities including the City of Rome itself and its eastern sister, Constantinople.[279]

According to Luttwak, Roman forts of the 1st/2nd centuries, whether castra legionaria (inaccurately translated as legionary "fortresses") or auxiliary forts, were clearly residential bases that were not designed to withstand assault. The typical rectangular "playing-card" shape, the long, thin and low walls and shallow ditch and the unfortified gates were not defensible features and their purpose was delimitation and keeping out individual intruders.[280] This view is too extreme, as all the evidence suggests that such forts, even the more rudimentary earlier type based on the design of marching-camps (ditch, earth rampart and wooden palisade), afforded a significant level of protection. The latter is exemplified by the siege of the legionary camp at Castra Vetera (Xanten) during the revolt of the Batavi in 69–70 AD. 5,000 legionaries succeeded in holding out for several months against vastly superior numbers of rebel Batavi and their allies under the renegade auxiliary officer Civilis, despite the latter disposing of c. 8,000 Roman-trained and equipped auxiliary troops and deploying Roman-style siege engines. (The Romans were eventually forced to surrender the fort by starvation).[281]

Nevertheless, later forts were undoubtedly built to much higher defensive specifications than their 2nd-century predecessors, including the following features:

- Deeper (average: 3 m) and much wider (av. 10 m) perimeter ditches (fossae). These would have flat floors rather than the traditional V-shape.[142] Such ditches would make it difficult to bring siege equipment (ladders, rams, and other engines) to the walls. It would also concentrate attackers in an enclosed area where they would be exposed to missile fire from the walls.[282]

- Higher (av. 9 m) and thicker (av. 3 m) walls. Walls were made of stone or stone facing with rubble core. The greater thickness would protect the wall from enemy mining. The height of the walls would force attackers to use scaling-ladders. The parapet of the rampart would have crenellations to provide protection from missiles for defenders.[283]

- Higher (av. 17.5 m) and projecting corner and interval towers. These would enable enfilading fire on attackers. Towers were normally round or half-round, and only rarely square as the latter were less defensible. Towers would be normally be spaced at 30米(98英尺) intervals on circuit walls.[284]

- Gate towers, one on each side of the gate and projecting out from the gate to allow defenders to shoot into the area in front of the entrance. The gates themselves were normally wooden with metal covering plates to prevent destruction by fire. Some gates had portcullises. Postern gates were built into towers or near them to allow sorties.[285]

More numerous than new-build forts were old forts upgraded to higher defensive specifications. Thus the two parallel ditches common around earlier forts could be joined by excavating the ground between them. Projecting towers were added. Gates were either rebuilt with projecting towers or sealed off by constructing a large rectangular bastion. The walls were strengthened by doubling the old thickness. Upgraded forts were generally much larger than new-build. New forts were rarely over one hectare in size and were normally placed to fill gaps between old forts and towns.[286] However, not all of the old forts that continued to be used in the 4th century were upgraded e.g. the forts on Hadrian's Wall and some other forts in Britannia were not significantly modified.[287]

The main features of late Roman fortification clearly presage those of medieval castles. But the defensibility of late Roman forts must not be exaggerated. Late Roman forts were not always located on defensible sites, such as hilltops and they were not designed as independent logistic facilities where the garrison could survive for years on internal supplies (water in cisterns or from wells and stored food). They remained bases for troops that would sally out and engage the enemy in the field.[288]

Nevertheless, the benefits of more defensible forts are evident: they could act as temporary refuges for overwhelmed local troops during barbarian incursions, while they waited for reinforcements. The forts were difficult for the barbarians to take by assault, as they generally lacked the necessary equipment. The forts could store sufficient supplies to enable the defenders to hold out for a few weeks, and to supply relieving troops. They could also act as bases from which defenders could make sorties against isolated groups of barbarians and to cooperate with relieving forces.[289]

The question arises as to why the 4th-century army needed forts with enhanced defensive features whereas the 2nd-century army apparently did not. Luttwak argues that defensible forts were an integral feature of a 4th-century defence-in-depth "grand strategy", while in the 2nd century "preclusive defence" rendered such forts unnecessary . But the existence of such a "strategy" is strongly disputed by several scholars, as many elements of the late Roman army's posture were consistent with continued forward defence.[290] An alternative explanation is that preclusive defence was still in effect but was not working as well as previously and barbarian raids were penetrating the empire more frequently.(see Strategy, below)

Strategy and tactics

Strategy

Edward Luttwak's Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire (1976) re-launched the thesis of Theodor Mommsen that in the 3rd and early 4th centuries, the empire's defence strategy mutated from "forward defence" (or "preclusive defence") in the Principate to "defence-in-depth" in the 4th century. According to Luttwak, the army of the Principate had relied on neutralising imminent barbarian incursions before they reached the imperial borders. This was achieved by stationing units (both legions and auxiliary regiments) right on the border and establishing and garrisoning strategic salients beyond the borders. The response to any threat would thus be a pincer movement into barbarian territory: large infantry and cavalry forces from the border bases would immediately cross the border to intercept the coalescing enemy army.[291]

According to Luttwak, the forward defence system was always vulnerable to unusually large barbarian concentrations of forces, as the Roman army was too thinly spread along the enormous borders to deal with such threats. In addition, the lack of any reserves to the rear of the border entailed that a barbarian force that successfully penetrated the perimeter defences would have unchallenged ability to rampage deep into the empire before Roman reinforcements from other border garrisons could arrive to intercept them.[292]

The essential feature of defence-in-depth, according to Luttwak, was an acceptance that the Roman frontier provinces themselves would become the main combat-zone in operations against barbarian threats, rather than the barbarian lands across the border. Under this strategy, border-forces (limitanei) would not attempt to repel a large incursion. Instead, they would retreat into fortified strongholds and wait for mobile forces (comitatenses) to arrive and intercept the invaders. Border-forces would be substantially weaker than under forward defence, but their reduction in numbers (and quality) would be compensated by the establishment of much stronger fortifications to protect themselves.[293]

But the validity of Luttwak's thesis has been strongly contested by a number of scholars, especially in a powerful critique by B. Isaac, the author of a leading study of the Roman army in the East (1992).[294][295][296] Isaac claims that the empire did not have the intelligence capacity or centralised military planning to sustain a grand strategy e.g. there was no equivalent to a modern army's general staff.[297] In any case, claims Isaac, the empire was not interested in "defence" at all: it was fundamentally aggressive both in ideology and military posture, up to and including the 4th century.[298]

Furthermore, there is a lack of substantial archaeological or literary evidence to support the defence-in-depth theory.[299] J.C. Mann points out that there is no evidence, either in the Notitia Dignitatum or in the archaeological record, that units along the Rhine or Danube were stationed in the border hinterlands.[300] On the contrary, virtually all forts identified as built or occupied in the 4th century on the Danube lay on, very near or even beyond the river, strikingly similar to the 2nd-century distribution.[301][302]

Another supposed element of "defence-in-depth" were the comitatus praesentales (imperial escort-armies) stationed in the interior of the empire. A traditional view is that the escort-armies' role was precisely as a strategic reserve of last resort that could intercept really large barbarian invasions that succeeded in penetrating deep into the empire (such as the invasions of the late 3rd century). But these large comitatus were not established before 312, by which time there had not been a successful barbarian invasion for c. 40 years. Also Luttwak himself admits that they were too distant from the frontier to be of much value in intercepting barbarian incursions.[303] Their arrival in theatre could take weeks, if not months.[304] Although the comitatus praesentales are often described as "mobile field-armies", in this context "immobile" would be a more accurate description. Hence the mainstream modern view that the central role of comitatus praesentales was to provide emperors with insurance against usurpers.[27]