Khazars: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 564203884 by 195.178.57.153 (talk)Please participate to the "talk" page before re-integrating litigious sections. Thanks in advance. |

|||

| Line 1,442: | Line 1,442: | ||

[[Category:Groups who converted to Judaism]] |

[[Category:Groups who converted to Judaism]] |

||

[[Category:Khaganates]] |

[[Category:Khaganates]] |

||

{{Link GA|de}} |

{{Link GA|de}} |

||

Revision as of 15:37, 14 July 2013

Hazar Kağanlığı Eastern Tourkia ממלכת הכוזרים Khazaria | |

|---|---|

| 618–1048 | |

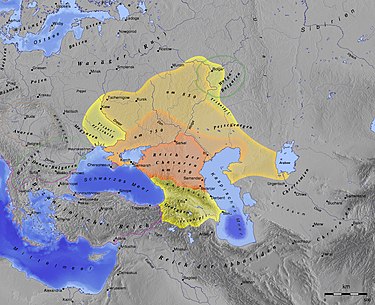

Khazar Khaganate, 650–850 | |

| Status | Khazar Khaganate |

| Capital | Balanjar (650-820) Atil (820-1048) |

| Common languages | Turkic Khazar |

| Religion | Tengriism, Shamanism, Christianity,[1] Slavic Paganism, Judaism,[2] and Islam |

| Khagan | |

• 618–628 | Tong Yabghu |

• 9th century | Obadiah |

• 9th century | Zachariah |

• 9th century | Bulan |

• 9th century | Benjamin |

• 9th century | Aaron |

• 9th century | Khan Tuvan |

• 10th century | Joseph |

• 10th century | Manasseh |

• 10th century | David |

• 11th century | Georgios |

| Historical era | Middle Ages |

• Established | 618 |

• Disestablished | 1048 |

| Population | |

• 7th Century[3] | 1,400,000 |

| Currency | Yarmaq |

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

| History of Tatarstan |

|---|

|

| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

|

|

|

The Khazars (Turkish: Hazarlar) were a semi-nomadic Turkic people who created one of the largest states of medieval Eurasia, Khazaria, with its capital at Atil. Astride one of the major arteries of commerce between northern Europe and southwestern Asia, Khazaria commanded the western marches of the Silk Road and played a key commercial role as a crossroad between China, the Middle East, and Europe.[4]

Khazaria served as a buffer state between Europe and the rising tide of Islamic conquest and enjoyed a strategic entente with the Christian Byzantine empire throughout the period of the Arab–Khazar Wars. The Khazars successfully staved off attempts by armies of the Umayyad Caliphate, beginning in 642, to penetrate north of the Caucasus. Beginning in the 8th century, the Khazar royalty and much of the aristocracy are reported to have converted to Judaism, though the populace remained multiconfessional and polyethnic. Between 965 and 969, the Khazar state was conquered by the Kievan Rus under Sviatoslav I of Kiev, who conquered Atil in 967.

Origins and languages

Determining the origins and nature of the Khazars is closely bound with theories of their language, but it is a matter of intricate difficulty since no indigenous records survive, and the state itself was polyglot and polyethnic.[5] The royal or ruling elite probably spoke an eastern variety of Shaz Turkic,[6] a language variously identified with Bulğaric, Chuvash, Uyğur, and Hungarian (the latter based upon the assertion of the Persian historian al-Iṣṭakhrī that the Khazar language was different from any other known tongue[7]). One method for tracing their origins consists in analysis of the possible etymologies behind the ethnonym Khazar itself.

Gyula Németh, following Zoltán Gombocz, derived Xazar from a hypothetical *Qasar reflecting a Turkic root qaz- (“to ramble, to roam”) being an hypothetical velar variant of Common Turkic kez-.[8] With the publication of the fragmentary Tes and Terkhin inscriptions of the Uyğur empire (744-840) where the form 'Qasar' is attested, though uncertainty remains whether this represents a personal or tribal name, gradually other hypotheses emerged. Louis Bazin derived it from Turkish qas- ("tyrannize, oppress, terrorize") on the basis of its phonetic similarity to the Uyğur tribal name, Qasar.[9] András Róna-Tas connects it with Kesar, the Pahlavi transcription of the Roman title Caesar.[10]

D.M.Dunlop tried to link the Chinese term for "Khazars" to one of the tribal names of the Uyğur Toquz Oğuz, namely the Gésà.[11][12] The objections are that Uyğur Gesa/Qasar was not a tribal name but rather the surname of the chief of the Sikari tribe of the Toquz Oğuz, and that in Middle Chinese the ethnonym "Khazars", always prefaced with the word Tūjué signifying ‘Türk’ (Tūjué Kěsà bù:突厥可薩部; Tūjué Hésà:突厥曷薩), is transcribed with different characters than that used to render the Qa- in the Uyğur word 'Qasar'.[13][14][15]

The Russian Military Encyclopedia, published in Saint Petersburg in 1911-1915, proposed its own version as a combination of Mongol words "Co" (protection, armor) and "zar" (frontier), so Cozar (meaning Khazar in Old Russian, Church Slavonic, and Ukrainian) might mean "a frontier protector", so long as the runic script used by the Khazars had originated in Mongolia.[16]

Tribal origins and early history

The tribes[17] constituting the Khazar union were, according to the most widely approved view, basically Turkish groups, such as the Oğuric peoples, including Šarağurs, Oğurs, Onoğurs, and Bulğars, who formed part of the Tiĕlè (鐵勒) confederation. These tribes, many driven out of their homelands by the Sabirs, who in turn fled the Asian Avars, began to flow into the Volga-Caspian-Pontic zone from as early as the 4th century CE and are recorded by Priscus to reside in the Western Eurasian steppelands as early as 463.[18][19] They appear to stem from Mongolia and South Siberia in the aftermath of the fall of the Hunnic/Xiōngnú nomadic polities. A variegated tribal federation led by these Tűrks, probably comprising a complex assortment of Iranian,[20] proto-Mongolic, Uralic, and Palaeo-Siberian clans, vanquished the Rouran Khaganate of the hegemonic central Asian Avars in 552 and swept westwards, taking in their train other steppe nomads and peoples from the Sogdian kingdom.[21]

The ruling family of this confederation may have hailed from the Āshǐnà (阿史那) clan of the West Türkic tribes,[22] though Zuckerman regards Āshǐnà and their pivotal role in the formation of the Khazars with scepticism.[23] Golden notes that Chinese and Arabic reports are almost identical, making the connection a strong one, and conjectures that their leader may have been Yǐpíshèkuì (Chinese:乙毗射匱), who lost power or was killed around 651.[24] Moving west, the confederation reached the land of the Akat(z)ir,[25] who had been important allies of Byzantium in fighting off Attila's army.

Rise of the Khazar state

An embryonic state of Khazaria began to form sometime after 630,[26] when it emerged out of the breakdown of the larger Göktürk qağanate. Göktürk armies had penetrated the Volga by 549, ejecting the Avars, who were then forced to flee to the sanctuary of the Hungarian plain. The Āshǐnà clan whose tribal name was ‘Türk’ (the strong one) appear on the scene by 552, when they overthrew the Rourans and established the Göktürk qağanate.[27] By 568, these Göktürks were probing for an alliance with Byzantium to attack Persia. An internecine war broke out between the senior eastern Göktürks and the junior West Turkic Qağanate some decades later, when on the death of Taspar Qağan, a succession dispute led to a dynastic crisis between Taspar’s chosen heir, the Apa Qağan, and the ruler appointed by the tribal high council, Āshǐnà Shètú (阿史那摄图), the Ishbara Qağan. By the first decades of the 7th century, the Āshǐnà yabgu Tong managed to stabilize the Western division, but on his death, after providing crucial military assistance to Byzantium in routing the Sassanid army in the Persian heartland,[28][29] the Western Turkic Qağanate dissolved under pressure from the encroaching Tang dynasty armies and split into two competing federations, each consisting of five tribes, collectively known as the “Ten Arrows” (On Oq). Both briefly challenged Tang hegemony in eastern Turkestan. To the West, two new nomadic states arose in the meantime, the Bulğar conferation, under Qubrat, the Duōlù clan leader, and the Nǔshībì subconfederation, also consisting of five tribes.[30] The Duōlù challenged the Avars in the Kuban River-Sea of Azov area while the Khazar Qağanate consolidated further westwards, led apparently by an Āshǐnà dynasty. With a resounding victory over the tribes in 657, engineered by General Sū Dìngfāng (蘇定方), Chinese overlordship was imposed to their East after a final mop-up operation in 659, but the two confederations of Bulğars and Khazars fought for supremacy on the western steppeland, and with the ascendency of the latter, the former either succumbed to Khazar rule or, as under Asperukh, Qubrat’s son, shifted even further west across the Danube to lay the foundations of the Bulğar state in the Balkans (ca. 679).[31][32]

The Qağanate of the Khazars thus took shape out of the ruins of this nomadic empire as it broke up under pressure from the Tang dynasty armies to the east sometime between 630-650.[24] After their conquest of the lower Volga region to the East and an area westwards between the Danube and the Dniepr, and their subjugation of the Onoğur -Bulğar union, sometime around 670, a properly constituted Khazar Qağanate emerges,[33] becoming the westernmost successor state of the formidable Göktürk Qağanate after its disintegration. According to Omeljan Pritsak, the language of the Onoğur-Bulğar federation was to become the lingua franca of Khazaria[34] as it developed into what Lev Gumilev called a 'steppe Atlantis' (stepnaja Atlantida/ Степная Атлантида).[35] The high status soon to be accorded this empire to the north is attested by Ibn al-Balḫî’s Fârsnâma (ca.1100), which relates that the Sassanid Shah, Ḫusraw 1, Anûsîrvân, placed three thrones by his own, one for the King of China, a second for the King of Byzantium, and a third for the king of the Khazars. Though anachronistic in retrodating the Khazars to this period, the legend, in placing the Khazar qağan on a throne with equal status to kings of the other two superpowers, bears witness to the reputation won by the Khazars from early times.[36][37]

The Khazar state: culture and institutions

Royal Diarchy and sacral Qağanate

Khazaria had two notable institutions: Dual kingship, a typical Turkic nomadic structure, and a sacral Qağanate. According to Arab sources, the lesser king was called îšâ and the greater king Xazar xâqân. The former managed both state and civilian affairs and the administration of the military, while the greater king‘s role was titular, not commanding obedience, and he was recruited from the Khazar house of notables (ahl bait ma‘rûfīn) in a ritual where the candidate is almost strangled until he declares the number of years he wishes to reign, on the expiration of which he was killed.[38][39][40] The deputy ruler would enter the presence of the reclusive greater king only with great ceremony, entering barefoot, prostrating himself in the dust, then lighting a piece of wood as a purifying fire, while waiting humbly and calmly to be summoned.[41] Particularly elaborate rituals accompanied a royal burial, with a palatial structure ('Paradise') constructed and then hidden under rerouted river water to avoid disturbance by evil spirits and later generations. Such a royal burial ground (qoruq) is typical of inner Asian peoples.[42] Both the îšâ and the xâqân converted to Judaism sometime in the 8th century, while the rest, according to the Persian traveller Ahmad ibn Rustah, probably followed the old Turkish religion.[43][44]

The Ruling Elite

The ruling strata, like that of the later Činggisids within the Golden Horde, was a relatively small group that differed ethnically and linguistically from its subject peoples,[45] composed of Alano-As and Oğuric Turkic tribes. The Khazar Qağans, while taking wives and concubines from the subject populations, were protected by a Khwârazmian guard corps or comitatus called the Ors/Orsiyya. But unlike many other local polities, they hired soldiers (mercenaries) (the junûd murtazîqa in al-Mas’ûdî).[46]

Settlements were governed by administrative officials known as tuduns. In some cases, such as the Byzantine settlements in southern Crimea, a tudun would be appointed for a town nominally within another polity's sphere of influence. Other officials in the Khazar government included dignitaries referred to by ibn Fadlan as Jawyshyghr and Kündür, but their responsibilities are unknown.

The People

It has been estimated that from 25 to 28 distinct ethnic groups made up the population of the Khazar Qağanate, aside from the ethnic elite. The ruling elite seems to have been constituted out of nine tribes/clans, themselves ethnically heterogeneous, spread over perhaps nine provinces or principalities, each of which would have been allocated to a clan.[39] In terms of caste or class, some evidence suggests that there was a distinction, whether racial or social is unclear, between "White Khazars" (ak-Khazars) and "Black Khazars" (qara-Khazars).[39] The 10th-century Muslim geographer al-Iṣṭakhrī claimed that the White Khazars were strikingly handsome with reddish hair, white skin, and blue eyes, while the Black Khazars were swarthy, verging on deep black, as if they were "some kind of Indian".[47] Many Turkic nations had a similar (political, not racial) division between a "white" ruling warrior caste and a "black" class of commoners; the consensus among mainstream scholars is that Istakhri was confused by the names given to the two groups.[48] However, Khazars are generally described by early Arab sources as having a white complexion, blue eyes, and reddish hair.[49][50] The name of the presumed founding Āshǐnà clan itself may reflect an etymology suggestive of a darkish colour.[51][52] The distinction appears to have survived the collapse of the Khazarian empire. Later Russian chronicles, commenting on the role of the Khazars in the magyarization of Hungary, refer to them as "White Ugrian" and Magyars as "Black Ugrians".[53]

Religious origins

Direct sources for Khazar religion are lacking, but in all likelihood they originally practiced a traditional Turkic form of cultic practices known as Tengriism, which focused on the sky god Tengri. Something of its nature may be deduced from what we know of the rites and beliefs of contiguous tribes, such as the North Caucasian Huns. Horse sacrifices were made to this supreme deity. Rites involved offerings to fire, water, and the moon, to remarkable creatures, and to "gods of the road". A tree cult was also maintained. Whatever was struck by lightning, man or object, was considered a sacrifice to the high god of heaven. The afterlife, to judge from excavations of aristocratic tumuli, was much a continuation of life on earth, warriors being interred with their weapons, horses, and sometimes with human sacrifices. Ancestor worship was observed. The key religious figure appears to have been a shamanizing qam.[54]

Many sources suggest, and a notable number of scholars have argued, that the charismatic Āshǐnà clan played a germinal role in the early Khazar state, though Zuckerman dismisses the widespread notion of their pivotal role as a 'phantom'. The Āshǐnà were closely associated with the Tengri cult, whose practices involved rites performed to assure a tribe of heaven’s protective providence.[55] The qağan was deemed to rule by virtue of qut, "the heavenly mandate/good fortune to rule."[56]

Army

At the peak of their empire, the Khazar permanent standing army may have numbered as many as 100,000, controlling or exacting tribute from thirty different nations and tribes inhabiting the vast territories between the Caucasus, the Aral Sea, the Ural Mountains, and the Ukrainian steppes.[57][58] Khazar armies were led by the Khagan Bek and commanded by subordinate officers known as tarkhans. When the bek sent out a body of troops, they would not retreat under any circumstances. If they were defeated, every one who returned was killed.[59] A famous tarkhan referred to in Arab sources as Ras or As Tarkhan led an invasion of Armenia in 758. The army included regiments of Muslim auxiliaries known as Arsiyah, of Khwarezmian or Alan extraction, who were quite influential. These regiments were exempt from campaigning against their fellow Muslims. Early Rus' sources sometimes referred to the city of Khazaran (across the Volga River from Atil) as Khvalisy and the Khazar (Caspian) sea as Khvaliskoye. According to scholars such as Omeljan Pritsak, these terms were East Slavic versions of "Khwarezmian" and referred to these as mercenaries. In addition to the Bek's standing army, the Khazars could call upon tribal levies in times of danger and were often joined by auxiliaries from subject nations.

Khazars and Byzantium

Byzantine diplomatic policy towards the steppe peoples generally consisted of encouraging them to fight among themselves. The Pechenegs provided great assistance to the Byzantines in the 9th century in exchange for regular payments.[60] Byzantium also sought alliances with the Göktürks against common enemies: in the early 7th century, one such alliance was brokered with the Western Tűrks against the Persian Sassanids in the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628. During the period leading up to and after the siege of Constantinople in 626, Heraclius sought help via emissaries, and eventually personally, from a Göktürk chieftain[61] of the Western Tűrkic Qağanate, Tong Yabghu Qağan, in Tiflis, plying him with gifts and the promise of marriage to his daughter, Epiphania.[62] Tong Yabghu responded by sending a large force to ravage the Persian empire, marking the start of the Third Perso-Turkic War.[63] A joint Byzantine-Tűrk operation breached the Caspian gates and sacked Derbent in 627. Together they then besieged Tiflis, where the Byzantines used traction trebuchets (ἑλέπόλεις) to breach the walls, one of their first known uses by the Byzantines.[citation needed] After the campaign, Tong Yabghu is reported, perhaps with some exaggeration, to have left some 40,000 troops behind with Heraclius.[64] Though occasionally identified with Khazars, the Göktürk identification is more probable since the Khazars only emerged from that group after the fragmentation of the former sometime after 630.[26] Sassanid Persia never recovered from the devastating defeat wrought by this invasion.[65]

Once the Khazars emerged as a power, the Byzantines also began to form alliances, dynastic and military, with them. In 695, the last Heraclian emperor, Justinian II, nicknamed the slit-nosed (ὁ ῥινότμητος) after he was mutilated and deposed, was exiled to Cherson in the Crimea, where a Khazar governor (tudun) presided. He escaped into Khazar territory in 704 or 705 and was given asylum by qağan Busir Glavan (Ἰβουζήρος Γλιαβάνος), who gave him his sister in marriage, perhaps in response to an offer by Justinian who may have thought a dynastic marriage would seal by kinship a powerful tribal support for his attempts to regain the throne.[66] The Khazarian spouse thereupon changed her name to Theodora.[67] Busir was offered a bribe by the Byzantine usurper, Tiberius III, to kill Justinian. Warned by Theodora, Justinian escaped, murdering two Khazar officials in the process. He fled to Bulgaria, whose Khan Tervel helped him regain the throne. Upon his reinstallment, and despite Busir's treachery during his exile, he sent for Theodora; Busir complied, and she was crowned as Augusta, suggesting that both prized the alliance.[68]

Decades later, Leo III (ruled 717-741) made a similar alliance to coordinate strategy against a common enemy, the Muslim Arabs. He sent an embassy to the Khazar qağan Bihar and married his son, the future Constantine V (ruled 741-775), to Bihar's daughter, a princess referred to as Tzitzak, in 732. On converting to Christianity, she took the name Irene. She introduced into the Byzantine court the distinctive kaftan or riding habit of the nomadic Khazars, the tzitzakion (τζιτζάκιον), which was to become a solemn element of imperial dress. Tzitzak is often treated as her original proper name, with a Turkic etymology čiček ('flower').[69] Erdal, however, citing the Byzantine work on court ceremony De Ceremoniis, authored by Constantine Porphyrogennetos, argues that the word referred only to the dress Irene wore at court, perhaps denoting its colourfulness, and compares it to the Hebrew ciciot, the knotted fringes of a ceremonial shawl tallit.[70] Constantine and Irene had a son, the future Leo IV (775-780), who thereafter bore the sobriquet, “the Khazar”.[71][72] Leo died in mysterious circumstances after his Athenian wife bore him a son, Constantine VI, who on his majority co-ruled with his mother, the dowager. He proved unpopular, and his death ended the dynastic link of the Khazars to the Byzantine throne.[citation needed]

Arab–Khazar wars

During the 7th and 8th centuries, the Khazars fought a series of wars against the Umayyad Caliphate and its Abbasid successor. The First Arab-Khazar War began during the first phase of Muslim expansion. By 640, Muslim forces had reached Armenia; in 642 they launched their first raid across the Caucasus under Abd ar-Rahman ibn Rabiah. In 652 Arab forces advanced on the Khazar capital, Balanjar, but were defeated, suffering heavy losses; according to Arab historians such as al-Tabari, both sides in the battle used catapaults against the opposing troops. A number of Russian sources give the name of a Khazar khagan from this period as Irbis and describe him as a scion of the Göktürk royal house, the Ashina. Whether Irbis ever existed is open to debate, as is whether he can be identified with one of the many Göktürk rulers of the same name.

Due to the outbreak of the First Muslim Civil War and other priorities, the Arabs refrained from repeating an attack on the Khazars until the early 8th century.[73] The Khazars launched a few raids into Transcaucasian principalities under Muslim dominion, including a large-scale raid in 683–685 during the Second Muslim Civil War that rendered much booty and many prisoners.[74] There is evidence from the account of al-Tabari that the Khazars formed a united front with the remnants of the Göktürks in Transoxiana.

The Second Arab-Khazar War began with a series of raids across the Caucasus in the early 8th century. The Ummayads tightened their grip on Armenia in 705 after suppressing a large-scale rebellion. In 713 or 714, Umayyad general Maslamah conquered Derbent and drove deeper into Khazar territory. The Khazars launched raids in response into Albania and Iranian Azerbaijan but were driven back by the Arabs under Hatin ibn al-Nu'man.[75] The conflict escalated in 722 with an invasion by 30,000 Khazars into Armenia inflicting a crushing defeat. Caliph Yazid II responded, sending 25,000 Arab troops north, swiftly driving the Khazars back across the Caucasus, recovering Derbent, and advancing on Balanjar. The Arabs broke through the Khazar defense and stormed the city; most of its inhabitants were killed or enslaved, but a few managed to flee north.[74] Despite their success, the Arabs had not yet defeated the Khazar army, and they retreated south of the Caucasus.

In 724, Arab general al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami inflicted a crushing defeat on the Khazars in a long battle between the rivers Cyrus and Araxes, then moved on to capture Tiflis, bringing Caucasian Iberia under Muslim suzerainty. The Khazars struck back in 726, led by a prince named Barjik, launching a major invasion of Albania and Azerbaijan; by 729, the Arabs had lost control of northeastern Transcaucasia and were thrust again into the defensive. In 730, Barjik invaded Iranian Azerbaijan and defeated Arab forces at Ardabil, killing the general al-Djarrah al-Hakami and briefly occupying the town. Barjik was defeated and killed the next year at Mosul, where he directed Khazar forces from a throne mounted with al-Djarrah's severed head. Arab armies led first by the prince Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik and then by Marwan ibn Muhammad (later Caliph Marwan II) poured across the Caucasus and in 737 defeated a Khazar army led by Hazer Tarkhan, briefly occupying Atil itself. The Qağan was forced to accept terms involving conversion to Islam, and to subject himself to the Caliphate, but the accommodation was short-lived as a combination of internal instability among the Umayyads and Byantine support undid the agreement within three years, and the Khazars re-asserted their independence.[76] The adoption of Judaism by the Khazars, which in this theory would have taken place around 740, may have been part of this re-assertion of independence.

Whatever the impact of Marwan's campaigns, warfare between the Khazars and the Arabs ceased for more than two decades after 737. Arab raids continued until 741, but their control in the region was limited as maintaining a large garrison at Derbent further depleted the already overstretched army. A third Muslim civil war soon broke out, leading to the Abbasid Revolution and the fall of the Umayyad dynasty in 750.

In 758, the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur attempted to strengthen diplomatic ties with the Khazars, ordering Yazid ibn Usayd al-Sulami, one of his nobles and the military governor of Armenia, to take a royal Khazar bride. Yazid married a daughter of Khazar Khagan Baghatur, but she died inexplicably, possibly in childbirth. Her attendants returned home, convinced that some Arab faction had poisoned her, and her father was enraged. Khazar general Ras Tarkhan invaded south of the Caucasus in 762–764, devastating Albania, Armenia, and Iberia, and capturing Tiflis. Thereafter relations became increasingly cordial between the Khazars and the Abbasids, whose foreign policies were generally less expansionist than the Umayyads, broken only by a series of raids in 799 over another failed marriage alliance.

Conversion

Surrounded by two powerful empires on its southern flank, each espousing a form of Abrahamic religion, the Khazars responded to the cultural challenge in a variety of ways. Many Khazars would retain fidelity to the older cult of Tengri, despite the pressures to convert. Christian proselytising missions, originating especially from Daghestan and Georgia, but also from the Goths, which had been assimilated by Khazars, had made some early ground in conversions within Khazaria territory. According to a report by al-Muqaddasi, most of the denizens of Samandar, a Khazar center, were Christians.[77] During the Islamic invasions, some groups of Khazars who suffered defeat, including a qağan, were converted to Islam.[78] Sometimes flight from social and religious oppression into a more tolerant sociopolitical culture accounted for the emergence in Khazaria of new religious groups. A number of Jews from both the Islamic world and Byzantium, for example, are known to have migrated to Khazaria, the latter fleeing, in one instance, the persecutions of Romanus Lakapēnos.[79]

According to a typical conversion legend, once when a Muslim doctor cured a local potentate and his wife within the Khazar realm on condition that they convert, the king of the Khazars came with a large army on a war footing, angered that they had converted without his command. Advised to fight, the local people, crying Allāhu akhbar, routed the Khazar army and forced the king to make peace, and he too converted to Islam.[80] Similar conversion legends, this time to Christianity, are recounted in Armenian records regarding “Huns” (probably Khazars) under their leader Alp’Ilit’uēr, who lay under the jurisdiction of the Khazar qağan. The account provides many details of the earlier shamanic-type cults practiced by these people before their conversion.[81]

Geographical extent

The Khazar Khaganate was an immense and powerful state at its height. The Khazaria heartland was the lower Volga and the Caspian coast as far south as Derbent. Khazar dominion over most of the Crimea and the northeast littoral of the Black Sea dates from the late 7th century. By 800 Khazar holdings included most of the Pontic steppe as far west as the Dnieper River and as far east as the Aral Sea (some Turkic history atlases show the Khazar sphere of influence extending well east of the Aral). During the Arab–Khazar war of the early 8th century, some Khazars evacuated to the foothills of the Ural Mountains, and some settlements may have remained. For a century and a half, the Khazars ruled the southern half of Eastern Europe and presented a bulwark blocking the Ural-Caspian gateway from Asia into Europe, while serving as a major artery of commerce between northern Europe and southwestern Asia along the Silk Road.

Their territory comprised much of modern-day southern European Russia, western Kazakhstan, eastern Ukraine, Azerbaijan, large portions of the northern Caucasus (Circassia, Dagestan), parts of Georgia, the Crimea, and northeastern Turkey.[82] Various place names invoking Khazar persist today. The Caspian Sea, traditionally known as the Hyrcanian Sea and Mazandaran Sea in Persian, is still known to Muslims as the 'Khazar Sea' (Bahr ul-Khazar).[83] Many other cultures still use the name "Khazar Sea", e.g. "Xəzər dənizi" in Azerbaijani, "Hazar Denizi" in Turkish, "Bahr ul-Khazar" in Arabic (although "Bahr Qazween" is becoming more popular now), and "Darya-ye Khazar" in Persian. In Hungary, there are villages (and people with family names) called Kozár and Kazár.

Khazar towns included the following:

- Along the Caspian coast and Volga delta: Atil; Khazaran; Samandar

- In the Caucasus: Balanjar; Kazarki; Sambalut; Samiran

- In Crimea and Taman region: Kerch (also called Bospor); Theodosia; Güzliev (modern Eupatoria); Samkarsh (also called Tmutarakan, Tamatarkha); Sudak (also called Sugdaia)

- In the Don valley: Sarkel

- A number of Khazar settlements have been discovered in the Mayaki-Saltovo region. Some scholars suppose that the Khazars founded a settlement called Sambat on the Dnieper, which was part of what would become the city of Kiev. Chernihiv is also thought to have started as a Khazar settlement.

Numerous nations were tributaries of the Khazars. A client king subject to Khazar overlordship was called an "Elteber". At various times, Khazar vassals included the following:

- On the Pontic steppes, Crimea, and Turkestan: The Pechenegs; the Oghuz; the Crimean Goths; the Crimean Huns (Onogurs); and the early Magyars.

- In the Caucasus mountains: Georgia;various Armenian principalities; Arran (Azerbaijan); the North Caucasian Huns; Lazica; the Caucasian Avars; the Kassogs; and the Lezgins.

- On the upper Don and Dnieper rivers: Various East Slavic tribes such as the Derevlians and the Vyatichs; and various early Rus' polities.

- On the Volga river: Volga Bulgaria; the Burtas; various Uralic forest tribes such as the Mordvins and Ob-Ugrians; the Bashkir; and the Barsils.

Khazars outside Khazaria

Khazar communities existed outside those areas under Khazar overlordship. Many Khazar mercenaries served in the armies of the Islamic Caliphates and other states. Documents from medieval Constantinople attest to a Khazar community mingled with the Jews of the suburb of Pera. Christian Khazars also lived in Constantinople, and some served in its armies, including, in the 9th and 10th centuries, the imperial Hetaireia bodyguard, where they formed their own separate company. The Patriarch Photius I of Constantinople was once angrily referred to by the Emperor as "Khazar-face", though whether this refers to his actual lineage or is a generic insult is unclear.

Polish legends speak of Jews being present in Poland before the establishment of the Polish monarchy. Polish coins from the 12th and 13th centuries sometimes bore Slavic inscriptions written in the Hebrew alphabet,[84][85] though connecting these coins to Khazar influence is purely a matter of speculation.

Khavars in Hungary

The Khavars (often called Kabars) who settled in Hungary in the late 9th and early 10th centuries may have included Khazars among their number. According to the archaeologist-historian Gábor Vékony, the native language of the Khavars was Khazar.[86] According to the Turkologist Prof. András Róna-Tas, part of the Khazars rebelled but were subverted by the Khagan; some joined with the Magyars and took part in the Settlement of Hungary at the end of the 9th century.[87]

Decline and fall

Khazars held hegemony over the Pontic steppe in the 9th century, a period known as the Pax Khazarica, allowing trade to flourish and facilitating trans-Eurasian contacts. In the early 10th century, however, the empire began to decline due to the attacks of Vikings from Kievan Rus and of various other Turkic tribes. Khazaria enjoyed a brief revival under the strong rulers Aaron II and Joseph, who subdued rebellious client states such as the Alans and led victorious wars against Rus' invaders. Later Rus' warlords, however, would finally destroy Khazar power.

Kabar rebellion and the departure of the Magyars

At some point in the 9th century (as reported by Constantine Porphyrogenitus), a group of three Khazar clans called the Kabars revolted against the Khazar government. Mikhail Artamonov, Omeljan Pritsak, and others have speculated that the revolt had something to do with a rejection of rabbinic Judaism; this is unlikely as it is believed that both the Kabars and mainstream Khazars had pagan, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim members. Pritsak maintained that the Kabars were led by the Khagan Khan-Tuvan Dyggvi in a war against the Bek, though he cited no primary source for his propositions. The Kabars were defeated and joined a confederacy led by the Magyars. It has been speculated that "Hungarian" derives from the Turkic word "Onogur", or "Ten Arrows", referring to two Uralic tribes and eight Turkic tribes (composed of Sabirs, Onogurs, and the three tribes of the Kabars).[88][89]

In the closing years of the 9th century the Khazars and Oghuz allied to attack the Pechenegs, who had been attacking both nations. The Pechenegs were driven westward, where they forced out the Magyars (Hungarians) who had previously inhabited the Don-Dnieper basin in vassalage to Khazaria. Under the leadership of the chieftain Lebedias, and later Árpád, the Hungarians, Kabars, and allied Russians moved west into modern-day Hungary, Transylvania, and Karpatian Rus. The departure of the Hungarians led to an unstable power vacuum and the loss of Khazar control over the steppes north of the Black Sea. Byzantine sources from the 10th and 11th centuries referred to Khazaria as Eastern Tourkia (Greek: Τουρκία) and to Hungary as Western Tourkia.[90][91]

Diplomatic isolation and military threats

The Khazar alliance with the Byzantine empire began to collapse in the early 10th century. Byzantine and Khazar forces may have clashed in the Crimea, and by the 940s emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogentius was speculating in De Administrando Imperio about ways in which the Khazars could be isolated and attacked. The Byzantines during the same period began to attempt alliances with the Pechenegs and the Rus', with varying degrees of success.

From the beginning of the 10th century, the Khazars found themselves fighting on multiple fronts as nomadic incursions were exacerbated by uprisings by former clients and invasions from former allies. According to the Schechter Text, the Khazar ruler Benjamin ben Menahem fought a war against a coalition of "'SY, TWRQY, 'BM, and PYYNYL," who were instigated and aided by "MQDWN". MQDWN or Macedon refers to the Byzantine Empire in many medieval Jewish writings; the other entities named have been tenuously identified by scholars, including Omeljan Pritsak, with the Burtas, Oghuz Turks, Volga Bulgars, and Pechenegs, respectively. Though Benjamin was victorious, his son Aaron II faced another invasion, this time led by the Alans. Aaron defeated the Alans with Oghuz help, yet within a few years the Oghuz and Khazars were enemies.

Ibn Fadlan reported Oghuz hostility to the Khazars during his journey, c. 921. Some sources, discussed by Tamara Rice, claim that Seljuk, the eponymous progenitor of the Seljuk Turks, began his career as an Oghuz soldier in Khazar service in the early and mid-10th century, rising to high rank before he fell out with the Khazar rulers and departed for Khwarazm.

The Rise of the Rus'

Contact with the Khazars put the Rus’ in contact with the Abbasid Caliphate, and Khazar administration of Rus' society was also of utility for them as a guide for how to govern a polyethnic and multiconfessional state. The Khazar language also had a significant impact as Russian absorbed a large quantity of Turkish words. According to Thomas Noonan, the currency of Khazar-Arab trade, the dirham, penetrated the Eastern Slavic world and attracted the Varangian Rus’, prompting the formation of a Rus’ state. The orderly hierarchical system of succession by ‘scales’ (lestvichnaia sistema:лествичная система) to the Grand Principate of Kiev was arguably modeled on Khazar institutions, via the example of the Rus' Khaganate.[92]

The Khazars were probably allied at some point with various Norse factions who controlled the region around Novgorod. The Rus' Khaganate, an early Rus' polity in modern northwestern Russia and Belarus, was probably heavily influenced by the Khazars. The Rus' regularly traveled through Khazar-held territory to attack territories around the Black and Caspian Seas; in one such raid, the Khagan is said to have given his assent on the condition that the Rus' give him half of the booty. In addition, the Khazars allowed the Rus' to use the trade route along the Volga River. This alliance was apparently fostered by the hostility between the Khazars and the Arabs. At a certain point, however, Khazar connivance of sacking Muslim lands by the Varangians led to a backlash against the Norsemen from the Muslim population of the Khaganate. The Khazar rulers closed the passage down the Volga to the Rus', sparking a war. In the early 960s, Khazar ruler Joseph wrote to Hasdai ibn Shaprut about the deterioration of Khazar relations with the Rus: "I have to wage war with them, for if I would give them any chance at all they would lay waste the whole land of the Muslims as far as Baghdad."

The Rus' warlords Oleg and Sviatoslav I of Kiev launched several wars against the Khazar Khaganate, often with Byzantine connivance. The Schechter Letter relates the story of a campaign against Khazaria by HLGW (Oleg) around 941 in which Oleg was defeated by the Khazar general Pesakh; this calls into question the timeline of the Primary Chronicle and other related works on the history of the Eastern Slavs. Sviatoslav finally succeeded in destroying Khazar imperial power in the 960s. The Khazar fortresses of Sarkel and Tamatarkha fell to the Rus' in 965, with the capital city of Atil following, circa 968 or 969. A visitor to Atil wrote soon after the sacking of the city: "The Rus' attacked, and no grape or raisin remained, not a leaf on a branch."

Trade

The Khazars occupied a prime trade nexus. Goods from western Europe travelled east to Central Asia and China and vice versa, and the Muslim world could only interact with northern Europe via Khazar intermediaries. The Radhanites, a guild of medieval Jewish merchants, had a trade route that ran through Khazaria, and they may have been instrumental in the conversion of the Khazars to Judaism.

No Khazar paid taxes to the central government. Revenue came from a ten percent levy on goods transiting through the region and from tribute paid by subject nations. The Khazars exported honey, furs, wool, millet and other cereals, fish, and slaves. D.M. Dunlop and Artamanov asserted that the Khazars produced no material goods themselves, living solely on trade. This theory has been refuted by discoveries over the last half century, which include pottery and glass factories.

Khazar coinage

The Khazars are known to have minted silver coins, called Yarmaqs. Many of these were imitations of Arab dirhems with corrupted Arabic letters. Coins of the Caliphate were in widespread use due to their reliable silver content. Merchants from as far away as China, England, and Scandinavia accepted them despite their inability to read the Arab writing. Thus, issuing imitation dirhems was a way to ensure acceptance of Khazar coinage in foreign lands.

Some surviving examples bear the legend "Ard al-Khazar" (Arabic for "land of the Khazars"). In 1999 a hoard of silver coins was discovered on the property of the Spillings farm on the Swedish island of Gotland. Among the coins were several dated 837/8 CE and bearing the legend, in Arabic script, "Moses is the Prophet of God" (a modification of the Muslim coin inscription "Muhammad is the Prophet of God").[94] In "Creating Khazar Identity through Coins", Roman Kovalev postulated that these dirhems were a special commemorative issue celebrating the adoption of Judaism by the Khazar ruler Bulan.[95]

Language

The language spoken by the Khazars is referred to as Khazarian, Khazaric, or Khazari. The language is extinct, and written records are almost non-existent. Few examples of the Khazar language exist today, mostly in names that have survived in historical sources. All of these examples seem to be of the "Lir"-type though. Extant written works are primarily in Hebrew.

The only Khazar word written in the original Khazar alphabet that survives is the single word-phrase OKHQURÜM, "I read (this or it)" (Modern Turkish: OKURUM), at the end of the Kievian Letter. This word is written in Turkic runiform script, suggesting that this script survived the conversion by the upper class to Judaism. Titles like alp, Bek (Modern Turkish "bey" means "chieftain, lord"), alp tarkan, and yabgu refer to an Oghuz Turkish root that is still spoken in Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Conversion of the royalty and aristocracy to Judaism

Jewish communities had existed in the Greek cities of the Black Sea coast since late classical times. Chersonesos, Sudak, Kerch, and other Crimean cities sustained Jewish communities, as did Gorgippia, and Samkarsh / Tmutarakan was said to have had a Jewish majority as early as the 670s. Jews fled from Byzantium to Khazaria as a consequence of persecution under Heraclius, Justinian II, Leo III, and Romanos I.[97] These were joined by other Jews fleeing from Sassanid Persia (particularly during the Mazdak revolts),[98] and later from the Islamic world. Jewish merchants such as the Radhanites regularly traded in Khazar territory and may have wielded significant economic and political influence. Though their origins and history are somewhat unclear, the Mountain Jews also lived in or near Khazar territory and may have been allied with the Khazars, or subject to them; it is conceivable that they, too, played a role in Khazar conversion.[citation needed]

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

At some point in the last decades of the 8th century or the early 9th century, the Khazar royalty and nobility converted to Judaism, and part of the general population may have followed.[99] The extent of the conversion is debated. The 10th century Persian historian Ibn al-Faqih reported that "all the Khazars are Jews." Notwithstanding this statement, most scholars believe that only the upper classes converted to Judaism;[100] there is some support for this in contemporary Muslim texts.[101]

Contemporary historians provided much detail about the religion and daily life of Khazars. One of the most detailed descriptions of Khazars came from Arab historian Ahmed ibn Fadlan, who traveled to Khazaria in 922 as the emissary of the Baghdad caliph. According to his account the majority of Khazars were Muslims and Christians, while the Jewish population represented a minority in the kingdom. According to ibn Fadlan, contrary to non-Jewish Khazars, the king and his royal court were Jewish. Ibn Fadlan claimed that 100,000 Muslims lived in Khazaria, and thirty mosques were established there. He also described a strong pagan community consisting mostly of Slavic peoples. Regarding governance, Ibn Fadlan wrote that judges were elected equally from Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Pagan communities.[102] Dmitry Vasilyev, a professor at Astrakhan State University who excavated sites associated with Khazars, states that after the fall of the Khazar empire, "Khazars were slowly assimilated by Turkic-speaking tribes, Tatars and Mongols."[103]

The Khazars enjoyed close relations with the Jews of the Levant and Persia. The Persian Jews, for example, hoped that the Khazars might succeed in conquering the Caliphate.[104] The high esteem in which the Khazars were held among the Jews of the Orient may be seen in the application to them, in an Arabic commentary on Isaiah ascribed by some to Saadia Gaon, and by others to Benjamin Nahawandi, of Isaiah 48:14: "The Lord hath loved him." "This", says the commentary, "refers to the Khazars, who will go and destroy Babel" (i.e., Babylonia), a name used to designate the country of the Arabs.[105] From the Khazar Correspondence it is apparent that two Spanish Jews, Judah ben Meir ben Nathan and Joseph Gagris, had succeeded in settling in the land of the Khazars. Saadia, who had a fair knowledge of the kingdom of the Khazars, mentions a certain Isaac ben Abraham who had removed from Sura to Khazaria.[106]

Khazar rulers maintained diplomatic correspondence with foreign countries, even as far away as Spain, and one exchange of letters has been between preserved between the Jewish king of Khazar Joseph and the Spanish rabbi Hasdai ibn Shaprut.[107] They were known to retaliate against Muslim or Christian interests in Khazaria in the wake of Islamic and Byzantine persecutions of Jews abroad.[108] Ibn Fadlan recounts that the king of Khazaria destroyed the minaret of a mosque in Atil as revenge for the destruction of a synagogue in Dâr al-Bâbûnaj, and allegedly said he would have done worse were it not for a fear that the Muslims might retaliate in turn against Jews.[109]

The theory that the majority of Ashkenazi Jews are the descendants of the Khazar population was advocated by various racial theorists[110][111] and antisemitic sources[111][112][113][114] in the 20th century, especially following the publication of Arthur Koestler's The Thirteenth Tribe. This belief is still popular among groups such as the Christian Identity Movement, Black Hebrews, British Israelitists, and others (particularly Arabs[115][116][117]) who claim that they, rather than Jews, are the true descendants of the Israelites, or who seek to downplay the connection between Ashkenazi Jews and Israel in favor of their own. For more detail on this controversy, see below.

Other religions

Besides Judaism, other religions practiced in areas ruled by the Khazars included Arianism, Greek Orthodox, Nestorian and Monophysite Christianity, and Zoroastrianism, as well as Norse, Finnic, and Slavic cults.[118] The Khazar government tolerated a wide array of religious practices within the Khaganate, and many Khazars reportedly were converts to Christianity and Islam. (See "Judiciary", below.)

A Greek Orthodox bishop was resident at Atil and was subject to the authority of the Metropolitan of Doros. The "apostle of the Slavs", Saint Cyril, is said to have attempted the conversion of Khazars without enduring results. Khazaran had a sizable Muslim population and quarter with a number of mosques. A Muslim officer, the khazz, represented the Muslim community in the royal court.

Debate about Khazar conversion to Judaism

Date and extent of the conversion

The date of the conversion of the Khazars to Judaism, and whether it occurred as one event or as a sequence of events over time, is widely disputed. The issues surrounding this controversy are discussed above.

The number of Khazars who converted to Judaism is also hotly contested, with historical accounts ranging from claims that only the King and his retainers had embraced Judaism, to the claim that the majority of the lay population had converted. D.M. Dunlop was of the opinion that only the upper class converted. Analysis of recent archaeological grave evidence by such scholars as Kevin A. Brook asserts that the sudden shift in burial customs, with the abandonment of pagan-style burial with grave goods and the adoption of simple shroud burials during the mid-9th century suggests a more widespread conversion.[119] A mainstream scholarly consensus does not yet exist regarding the extent of the conversions.

Karaims

Turkic-speaking Karaites (in the Crimean Tatar language, Qaraylar) have lived in Crimea for centuries. Their origin is a matter of great controversy. According the Karaite documents[120][121][122][123][124] at the near past they considered themselves as Karaite Jews who settled in Crimea and adopted the «language of the nomads»[125] (see Karaim language). Currently most of them consider themselves, as descendants of Khazar or Kipchak converted to Karaimism. This theory was originally suggested by Russian orientalist V. Grigoriev in the 19th century,[126] has been widely adopted by the Karaims in the 20th century.[127] (See also Seraya Shapshal).

Specialists in Khazar history put the Khazar theory questioned,[128] highlighting the following facts:

- Karaim language belongs to the Kipchak linguistic group, and the Khazar - the Bulgar, therefore, between the two Turkic languages is no close relationship;[129]

- According Khazar Correspondence Khazar Judaism was, most likely, Talmudic, and in the tradition of Karaism the only holy book is the Bible, the Talmud is not recognized;

- Khazars disappeared in the 11th century, and the first written mention of the Crimean Karaites was in the 14th century.[130]

Today most of the Karaims seek to distance themselves from being identified as Karaite Jews, emphasizing their Turkic heritage as Turkic practitioners of a "Mosaic religion separate and distinct from Judaism", is in-keeping with their study of Halakah Shammai.[131]

Krymchaks

The Krymchaks are Turkic people, community of Turkic languages and adherents of Rabbinic Judaism living in Crimea. In the late 7th century most of Crimea fell to the Khazars. The extent to which the Krymchaks influenced the ultimate conversion of the Khazars and the development of Khazar Judaism is unknown. During the period of Khazar rule, intermarriage between Crimean Jews and Khazars is likely, and the Krymchaks probably absorbed numerous Khazar refugees during the decline and fall of the Khazar kingdom (a Khazar successor state, ruled by Georgius Tzul, was centered on Kerch). It is known that Kipchak converts to Judaism existed, and it is possible that from these converts the Krymchaks adopted their distinctive language. They have historically lived in close proximity to the Karaims. At first krymchak was a Russian descriptive used to differentiate them from their Ashkenazi coreligionists, as well as other Jewish communities in the former Russian Empire such as the Georgian Jews, but in the second half of the 19th century this name was adopted by the Krymchaks themselves.

Theory of Khazar ancestry of Ashkenazi Jews

Early Khazar theories

The theory that all or most Ashkenazi Jews might be descended from Khazars dates back to the racial studies of late 19th-century Europe. In some cases it has been cited to assert that most modern Jews are not descended from Israelites and/or to refute Israeli claims to Israel. It was first publicly proposed in a lecture given by the racial-theorist Ernest Renan on January 27, 1883, titled "Judaism as a Race and as Religion."[132] It was repeated in articles in The Dearborn Independent in 1923 and 1925, and popularized by racial theorist Lothrop Stoddard in a 1926 article in the Forum titled "The Pedigree of Judah", where he argued that Ashkenazi Jews were a mix of people, of which the Khazars were a primary element.[111][133] Stoddard's views were "based on nineteenth and twentieth-century concepts of race, in which small variations on facial features as well as presumed accompanying character traits were deemed to pass from generation to generation, subject only to the corrupting effects of marriage with members of other groups, the result of which would lower the superior stock without raising the inferior partners."[134] This theory was adopted by British Israelites, who saw it as a means of invalidating the claims of Jews (rather than themselves) to be the true descendants of the ancient Israelites, and was supported by early anti-Zionists.[111][133]

In 1951 Southern Methodist University professor John O. Beaty published The Iron Curtain over America, a work which claimed that "Khazar Jews" were "responsible for all of America's — and the world's — ills beginning with World War I". The book repeated a number of familiar claims, placing responsibility for U.S. involvement in World Wars I and II and the Bolshevik revolution on these Khazars, and insisting that Khazar Jews were attempting to subvert Western Christianity and establish communism throughout the world. The American millionaire J. Russell Maguire gave money towards its promotion, and it was met with enthusiasm by hate groups and the extreme right.[112][113] By the 1960s the Khazar theory had become a "firm article of faith" amongst Christian Identity groups.[111][114] In 1971 John Bagot Glubb (Glubb Pasha) also took up this theme, insisting that Palestinians were more closely related to the ancient Judeans than were Jews. According to Benny Morris:

Of course, an anti-Zionist (as well as an anti-Semitic) point is being made here: The Palestinians have a greater political right to Palestine than the Jews do, as they, not the modern-day Jews, are the true descendants of the land's Jewish inhabitants/owners.[116]

The theory gained further support when the Jewish novelist Arthur Koestler devoted his popular book The Thirteenth Tribe (1976) to the topic. Koestler's historiography has been attacked as highly questionable by many historians.[115][135][136] To the extent that Koestler referred to place-names and documentary evidence, his critics have described it as a mixture of flawed etymologies and misinterpreted primary sources.[137] Commentors have also noted that Koestler mischaracterized the sources he cited, particularly D.M. Dunlop's History of the Jewish Khazars (1954).[136] Dunlop himself stated that the theory that Eastern European Jews were the descendants of the Khazars, "... can be dealt with very shortly, because there is little evidence which bears directly upon it, and it unavoidably retains the character of a mere assumption."[138]

Unlike many of his critics, Koestler, a secular Ashkenazi Jew, did not fear alleged Khazar ancestry as diminishing the claim of Jews to Israel, which he felt was based on the United Nations mandate, and not on Biblical covenants or genetic inheritance. In his view, "The problem of the Khazar infusion a thousand years ago ... is irrelevant to modern Israel". In addition, according to author Michael Barkun, Koestler was apparently "either unaware of or oblivious to the use anti-Semites had made to the Khazar theory since its introduction at the turn of the [20th] century."[139]

In the 1970s and 80s the Khazar theory was also advanced by the school of Mikhail Artamonov, discussing the common roots of Chuvashians, Ukrainians and Jews due to many common culture and anthropological features. One of its members, the historian and the geographer Lev Gumilyov, portrayed "Judeo-Khazars" as having repeatedly sabotaged Russia's development since the 7th century, while Orthodox Catholic Khazars only turned into Cossacks, Ukrainians and Russians, in his opinion.[140][141][142]

Genetic studies on Ashkenazi Jewry

A 1999 study by Hammer et al., published in the Proceedings of the United States National Academy of Sciences compared the Y chromosomes of Ashkenazi, Roman, North African, Kurdish, Near Eastern, Yemenite, and Ethiopian Jews with 16 non-Jewish groups from similar geographic locations. It found that "Despite their long-term residence in different countries and isolation from one another, most Jewish populations were not significantly different from one another at the genetic level... The results support the hypothesis that the paternal gene pools of Jewish communities from Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East descended from a common Middle Eastern ancestral population, and suggest that most Jewish communities have remained relatively isolated from neighboring non-Jewish communities during and after the Diaspora."[143] According to Nicholas Wade "The results accord with Jewish history and tradition and refute theories like those holding that Jewish communities consist mostly of converts from other faiths, or that they are descended from the Khazars, a medieval Turkish tribe that adopted Judaism."[144]

A 2010 study on Jewish ancestry by Atzmon et al. says "Two major groups were identified by principal component, phylogenetic, and identity by descent (IBD) analysis: Middle Eastern Jews and European/Syrian Jews. The IBD segment sharing and the proximity of European Jews to each other and to southern European populations suggested similar origins for European Jewry and refuted large-scale genetic contributions of Khazars or Slavic populations to the formation of Ashkenazi Jewry."[145]

Concerning male-line ancestry, several Y-DNA studies have tested the hypothesis of Khazar ancestry amongst Ashkenazim.[146][147][148] In these studies Haplogroup R1a chromosomes (sometimes called Eu 19) have been identified as potential evidence of one line of Eastern European ancestry amongst Ashkenazim, which could possibly be Khazar. One concluded that "neither the NRY haplogroup composition of the majority of Ashkenazi Jews nor the microsatellite haplotype composition of the R1a1 haplogroup within Ashkenazi Levites is consistent with a major Khazar or other European origin", athough "one cannot rule out the important contribution of a single or a few founders among contemporary Ashkenazi Levites."[147] Another concluded that "if the R-M17 chromosomes in Ashkenazi Jews do indeed represent the vestiges of the mysterious Khazars then, according to our data, this contribution was limited to either a single founder or a few closely related men, and does not exceed ~ 12% of the present-day Ashkenazim."[146]

In August 2012, Dr. Harry Ostrer stated in his book "Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People" that all major Jewish groups do have common Middle Eastern origin, originating from ancient Israelites, and refuted any large scale genetic contribution from the Turkic Khazars.[149]

Geneticist Noah Rosenberg asserts that although recent DNA studies "do not appear to support" the Khazar hypothesis, they do not "entirely eliminate it either."[150] while Sarah Tishkoff, a geneticist at the University of Pennsylvania, commenting on the results of genetic studies stated "This is clearly showing a genetic common ancestry of all Jewish populations."[151]

However, in December 2012, Johns Hopkins geneticist Eran Elhaik released research that he says offers strong evidence that the Khazar theory is at least partially true.[152]

Other claims of descent

The Khazar origin is maintained by the folklore of such groups as the Mountain Jews and Georgian Jews. There is little evidence in English-language literature to support these theories, although it is possible that some Khazar descendants found their way into these communities. Non-Jewish groups who claim at least partial descent from the Khazars include the Kazakhs, Kumyks, and Crimean Tatars; as with the above-mentioned Jewish groups, these claims are subject to a great deal of controversy and debate. The Russian Orthodox Catholic Cossacks of southern Russia and Ukraine, many of whom live in Russian krais that were once part of the former Khazaria, are sometimes said to be of partially Turkic origin, including Khazar as well as Tatar, Cuman, and Pecheneg, due to their tradition of calling themselves Khazars (Cossar (Cassar) in Russian, Cossarluge in Ukraininan), as well as their constitutions (such as the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk) and aspects of their customs and lifestyle. The Mishari, a group of Tatars, are said to be of Khazar origin according to sources in Russian and Tatar languages.[153] The Magyars who would later found Hungary also had lived in Khazaria for hundreds of years, and are also of partially Khazar origin themselves, as the Kabar subgroup of the Khazars joined the Magyars and was later absorbed by them, although they are a Uralic group otherwise apparently unrelated to the Turkic peoples.

Late references to the Khazars

The temporal and geographic extent of Khazar polities following the sack of Atil by Sviatoslav in 968/9, and even whether any such states existed, is unclear. The Khazars may have retained control over some areas in the Caucasus for another two centuries, but sparse historical records make this difficult to confirm. Evidence of later Khazar polities includes the fact that Sviatoslav did not occupy the Volga basin after he conquered Atil, departing relatively quickly to embark on his campaign in Bulgaria.

Russian garrisons left the Atil area about 990. The permanent conquest of the Volga basin seems to have been left to later waves of steppe peoples like the Kipchaks (Cumans) in 1050-1060, but in the 12th century the territory remained under the sovereignty of the Volga Bulgarians claiming Khazar descent themselves.[154]

Jewish sources

A letter in Hebrew, the Mandgelis Document, dated AM 4746 (985–986), refers to "our lord David, the Khazar prince" who lived in Taman. The letter said that this David was visited by envoys from Kievan Rus' to ask about religious matters — this could be connected to the conversion of Vladimir during the same period. Taman was a principality of Kievan Rus' around 988, so this successor state (if that is what it was) may have been conquered altogether. The authenticity of this letter has been questioned, however, by scholars such as D. M. Dunlop.

Petachiah of Ratisbon, a 13th-century rabbi and traveler, reported traveling through "Khazaria", though he gave few details of its inhabitants except to say that they lived amidst desolation in perpetual mourning. The account of the conversion of the "seven kings of Meshech" is extremely similar to the accounts of the Khazar conversion given in the Kuzari and in King Joseph's Reply. It is possible that Meshech refers to the Khazars or to some Judaized polity influenced by them. Arguments against this possibility include the reference to "seven kings" (though this, in turn, could refer to seven successor tribes or state micropolities).

Arabic and Muslim sources

Ibn Hawqal and al-Muqaddasi refer to Atil after 969, indicating that it may have been rebuilt. Al-Biruni (mid-11th century) reported that Atil was in ruins and did not mention the later city of Saqsin, which was built nearby, so it is possible that this new Atil was only destroyed in the middle of the 11th century. Even assuming al-Biruni's report was not an anachronism, there is no evidence that this "new" Atil was populated by Khazars rather than by Pechenegs or a different tribe.

Ibn al-Athir, who wrote around 1200, described "the raid of Fadhlun the Kurd against the Khazars". Fadhlun the Kurd has been identified as al-Fadhl ibn Muhammad al-Shaddadi, who ruled Arran and other parts of Azerbaijan in the 1030s. According to the account he attacked the Khazars but had to flee when they ambushed his army and killed 10,000 of his men. Two of the great early 20th century scholars on Eurasian nomads, Marquart and Barthold, disagreed about this account. Marquart believed that this incident refers to some Khazar remnant that had reverted to paganism and nomadic life. Barthold, and more recently, Kevin Brook, took a much more skeptical approach and said that ibn al-Athir must have been referring to Georgians or Abkhazians. There is no evidence to resolve the issue one way or the other.

Kievan Rus' sources

According to the Primary Chronicle, in 986 Khazar Jews were present at Vladimir's disputation to decide on the prospective religion of the Kievian Rus'. Whether these were Jews who had settled in Kiev or emissaries from some Jewish Khazar remnant state is unclear. The whole incident is regarded by a few radical scholars as a fabrication, but the reference to Khazar Jews (after the destruction of the Khaganate) is still relevant. Heinrich Graetz alleged that these were Jewish missionaries from the Crimea, but provided no reference to primary sources for his allegation.

In 1023 the Primary Chronicle reports that Mstislav of Chernigov (one of Vladimir's sons) marched against his brother Yaroslav with an army that included "Khazars and Kasogs". Kasogs were an early Circassian people. "Khazars" in this reference is considered by most to be intended in the generic sense, but some have questioned why the reference reads "Khazars and Kasogs", when "Khazars" as a generic would have been sufficient. Even if the reference is to Khazars, of course, it does not follow that there was a Khazar state in this period. They could have been Khazars under the rule of the Rus.

A Kievian prince named Oleg (not to be confused with Oleg of Kiev) was reportedly kidnapped by "Khazars" in 1078 and shipped off to Constantinople, although most scholars believe that this is a reference to the Kipchaks or other steppe peoples then dominant in the Pontic region. Upon his conquest of Tmutarakan in the 1080s Oleg gave himself the title "Archon of Khazaria".

Byzantine, Georgian and Armenian sources

Kedrenos documented a joint attack on the Khazar state in Kerch, ruled by Georgius Tzul, by the Byzantines and Russians in 1016. Following 1016, there are more ambiguous references in Eastern Christian sources to Khazars that may be using "Khazars" in a general sense (the Arabs, for example, called all steppe people "Turks", while the Romans/Byzantines called them all "Scythians"). At least one Byzantine source from the 12th century refers to tribes practicing Mosaic law and living in the Balkans (see Khalyzians). The connection between this group and the Khazars, however, is rejected by most modern Khazar scholars.

Western sources

Giovanni di Plano Carpini, a 13th-century Papal legate to the court of the Mongol Khan Guyuk, gave a list of the nations the Mongols had conquered in his account. One of them, listed among tribes of the Caucasus, Pontic steppe, and Caspian region, was the "Brutakhi, who are Jews." The identity of the Brutakhi is unclear. Giovanni later refers to the Brutakhi as shaving their heads. Though Giovanni refers to them as Kipchaks, they may have been a remnant of the Khazar people. Alternatively, they may have been Kipchak converts to Judaism (possibly connected to the Krymchaks or the Karaims).

In literature

The Kuzari is one of most famous works of the medieval Spanish Jewish philosopher and poet Rabbi Yehuda Halevi (c. 1075–1141). Divided into five essays ("ma'amarim" (namely, Articles)), it takes the form of a dialogue between the pagan king of the Khazars and a Jew who was invited to instruct him in the tenets of the Jewish religion. Originally written in Arabic, the book was translated by numerous scholars (including Judah ibn Tibbon) into Hebrew and other languages. Though the book is not considered a historical account of the Khazar conversion to Judaism, scholars such as D.M. Dunlop and A.P. Novoseltsev have postulated that Yehuda had access to Khazar documents upon which he loosely based his work. His contemporary Avraham ibn Daud reported meeting Khazar rabbinical students in Toledo, Spain in the mid-12th century. In any case, however, the book is in the main—and clearly intended to be—an exposition of the basic tenets of the Jewish religion, rather than a historical account of the actual conversion of the Khazars to Judaism.

The question of mass religious conversion is a central theme in Milorad Pavić's international bestselling novel Dictionary of the Khazars. The novel, however, contained many invented elements and had little to do with actual Khazar history. More recently, several novels, including H.N. Turteltaub's Justinian (about the life of Justinian II) and Marek Halter's Book of Abraham and Wind of the Khazars, have dealt either directly or indirectly with the topic of the Khazars and their role in history.

In 2007, the New York Times Magazine serialized a novel by Michael Chabon entitled Gentlemen of the Road, which features 10th-century Khazar characters.

See also

Notes

Citations

- ^ Golden 2007b, p. 136

- ^ Wexler 1996, p. 50

- ^ Herlihy 1972, pp. 136–148;Russell1972, pp. 25–71.This figure has been calculated on the basis of the data in both Herlihy and Russell's work.

- ^ Allsen 1997, pp. 2–23

- ^ Erdal 2007, p. 75, n.2.'there must have been many different ethnic groups within the Khazar realm. . . These groups spoke different languages, some of them no doubt belonging to the Indo-European or different Caucasian language families.'

- ^ Golden 2006, p. 91.'Oğuric Turkic, spoken by many of the subject tribes,doubtless, was one of the linguae francae of the state. Alano-As was also widely spoken. Eastern Common Turkic, the language of the royal house and its core tribes, in all likelihood remained the language of the ruling elite in the same way that Mongol continued to be used by the rulers of the Golden Horde, alongside of the Qipčaq Turkic speech spoken by the bulk of the Turkish tribesmen that constituted the military force of this part of the Činggisid empire. Similarity, Oğuric, like Qipčaq Turkic in the Jočid realm, functioned as one of the languages of government.'

- ^ Golden 2007a, pp. 13–14, 14 n.28. al-Iṣṭakhrī ‘s account however then contradicts itself by likening the language to Bulğaric.

- ^ Golden 2007a, p. 15

- ^ Golden 2007a, p. 16 and n.38 citing L. Bazin, 'Pour une nouvelle hypothèse sur l'origine des Khazar,' in Materialia Turcica, 7/8 (1981-1982): 51-71.

- ^ Golden 2007a, p. 16.Compare Tibetan dru-gu Gesar (the Turk Gesar).

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 34–40

- ^ Golden 2007a, p. 16

- ^ Golden 2007a, p. 17.Kěsà (可薩) would have been pronounced something like kha’sat in both Early Middle Chinese/EMC and Late Middle Chinese/LMC while Hésà (曷薩) would yield γat-sat in (EMC) and xɦat sat (LMC) respectively, where final ‘t’ often transcribes –r- in foreign words. Thus, while these Chinese forms could transcribe a foreign word of the type *Kasar/*Kazar, *Gatsar,*Gazr,*Gasar, there is a problem phonetically with assimilating these to the Uyğur word Qasar/ Gesa (EMC/LMC Kat-sat= Kar sar=*Kasar).

- ^ Shirota 2005, pp. 235, 248.

- ^ Brook 2009, p. 5

- ^ Military Encyclopedia. Saint Petersburg, 1911-1915, p. 273-278, Казаки, казачество, казачьи войска // Военная энциклопедия / Под ред. В. Ф. Новицкого и др.. — СПб.: т-во И. В. Сытина, 1911—1915. — Т. 11. — С. 273−278.

- ^ Golden 2001b, p. 78.'The word tribe is as troublesome as the term clan. It is commonly held to denote a group, like the clan, claiming descent from a common (in some ulture zones eponymous) ancestor, possessing a common territory, economy, language, culture, religion, and sense of identity. In reality, tribes were often highly fluid sociopolitical structures, arising as "ad hoc responses to ephemeral situations of competitition," as Morton H. Fried has noted.'

- ^ Golden 2007a, p. 14

- ^ Szádeczky-Kardoss 1994, p. 206

- ^ Golden 2007a, pp. 40–41;Brook 2009, p. 4 note that Dieter Ludwig, in his doctoral thesis Struktur und Gesellschaft des Chazaren-Reiches im Licht der schriftlichen Quellen, (Münster,1982) suggested that the Khazars were Turkic members of the Hephthalite Empire, where the lingua franca was a variety of Iranian.

- ^ Golden 2006, p. 86

- ^ Golden 2007a, p. 53,

- ^ Zuckerman 2007, p. 404.Cf.'The reader should be warned that the A-shih-na link of the Khazar dynasty, an old phantom of . . Khazarology, will . .lose its last claim to reality'.

- ^ a b Golden 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Golden 2006, pp. 89–90. In this view, the name Khazar would derive from a hypothetical *Aq Qasar.

- ^ a b Kaegi 2003, p. 143 n.115, citing also Golden 1992, pp. 127–136, 234–237.

- ^ Whittow 1996, p. 221. The word Türk, Whittow adds, had no strict ethnic meaning at the time: 'Throughout the early middle ages on the Eurasian steppes, the term ‘Turk’ may or may not imply membership of the ethnic group of Turkic peoples, but it does always mean at least some awareness and acceptance of the traditions and ideology of the Gök Türk empire, and a share, however distant, in the political and cultural inheritance of that state.'

- ^ Kaegi 2003, pp. 154–186.

- ^ Whittow 1996, p. 222.

- ^ Golden 2010, pp. 54–55 The Duōlù (咄陆) were the left wing of the On Oq, the Nǔshībì (弩失畢: *Nu Šad(a)pit), and together they were registered in Chinese sources as the 'ten names' (shí míng:十名).

- ^ Golden 2001b, pp. 94–5.

- ^ Somogyi 2008, p. 128.

- ^ Zuckerman 2007, p. 417

- ^ Golden 2006, p. 90.

- ^ Golden 2007a, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Golden 2007a, pp. 7–8

- ^ Golden 2001b, p. 73

- ^ Dunlop 1954, pp. 97, 112. The nobles would kill him if his reign lasted even one day beyond the specified number of years. Ibn Fadlan gave a precise figure for the maximum number of years allotted to a king's reign. If a Qağan had ruled for at least forty years, Fadlan wrote, his courtiers and subjects felt that his ability to reason had become impaired on account of his old age. They would then kill the Qağan.

- ^ a b c Noonan 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Golden 2006.

- ^ Golden 2007b, pp. 133–4.

- ^ de Weese 1994, p. 181.

- ^ Golden, 2006 & pp.79-81.

- ^ Golden 2007b, pp. 130–131: 'the rest of the Khazars profess a religion similar to that of the Turks.'

- ^ Golden 2006, p. 88.

- ^ Golden 2006, pp. 79–80, 88.

- ^ Dunlop 1954, p. 96

- ^ Brook 2009, pp. 3–4

- ^ Patai & Patai 1989, p. 70.

- ^ Brook 2009, p. 3

- ^ Golden 2006, pp. 86 n.39, 89The ethnonym in the Tang Chinese annals, Āshǐnà (阿史那), often accorded a key role in the Khazar leadership, may reflect an Eastern Iranian or Tokharian word (Khotanese Saka âşşeina-āššsena ‘blue’): Middle Persian axšaêna (‘dark-coloured’): Tokharian A âśna (‘blue’, ‘dark’).

- ^ Luttwak 2009, p. 152.

- ^ Oppenheim 1994, p. 312.

- ^ Golden 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Whittow 1996, p. 220

- ^ Golden 2007b, p. 133. Whittow 1996, p. 220 notes that this native institution, given the constant, lengthy, military and acculturating pressures on the tribes from China to the East, was influenced also by the sinocentric doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven (Tiānmìng:(天命), which signaled legitimacy of rule.

- ^ Bury, J. B., A History of the Eastern Roman Empire (London, 1912).

- ^ Koestler 1977, p. 18

- ^ Dunlop 1954, p. 113

- ^ Luttwak 2009, p. 52

- ^ Many sources identify the Göktürks in this alliance as Khazars, for example, Beckwith writes recently:'The alliance sealed by Heraclius with the Khazars in 627 was of seminal importance to the Byantine Empire through the Early Middle Ages, and helped assure its long-term survival.'Beckwith 2011, pp. =120, 122. Early sources such as the almost contemporary Armenian history,Patmutʿiwn Ałuanicʿ Ašxarhi attributed to Movsēs Dasxurancʿ, and the Chronicle attributed to Theophanes identify these Turks as Khazars (Theophanes has: 'Turks, who are called Khazars'). Both Zuckerman and Golden reject the identification Zuckerman 2007, pp. 403–404.

- ^ Kaegi 2003, pp. 143–145.

- ^ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 230.

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Zuckerman 2007, p. 417. Scholars dismiss Chinese annals which, reporting the events from Turkic sources, attribute the destruction of Persia and its leader Shah Khusrau II personally to Tong Yabghu. Zuckerman argues instead that the account is correct in its essentials.

- ^ Bauer 2010, p. 341.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1969, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Cameron 1984, p. 212. By 711, however, Busir was supporting, possibly instigating,[citation needed] a revolt in Cherson among Byzantine troops led by another exile, rebel general Bardanes, who seized the throne as Emperor Philippikos and killed Justinian.

- ^ Wexler 1987, p. 72.

- ^ Erdal 2007, p. 80, n.22.

- ^ Luttwak 2009, pp. 137–8

- ^ Piltz 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Mako 2010, p. 45

- ^ a b Brook 2009, pp. 126–7

- ^ Brook 2009, pp. 127

- ^ Wasserstein 2007, pp. 375–376

- ^ Golden 2007b, pp. 135–136.

- ^ de Weese 1994, p. 73.

- ^ Noonan 2001, pp. 77–78.

- ^ de Weese 1994, p. 76.

- ^ de Weese 1994, pp. 292–29873.

- ^ Encyclopaedic ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia: A-I, Volume 1 By R. Khanam

- ^ William Edward David Allen, A History of the Georgian People: From the Beginning Down to the Russian Conquest in the Nineteenth Century,Taylor & Francis, 1932p.10

- ^ Jewish Encyclopædia.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopædia.

- ^ Vékony, Gábor (2004): A székely rovásírás emlékei, kapcsolatai, története [The Relics, Relations and the History of the Szekely Rovas Script]. Publisher: Nap Kiadó, Budapest. p. 217

- ^ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 56

- ^ Érdy, Miklós. A Magyarság Keleti Eredete és Hun Kapcsolata. 2010. ISBN 978-963-662-369-2

- ^ Petrik, István. Rejtélyek Országa. 2008. ISBN 978-963-263-006-9

- ^ Peter B. Golden, Nomads and their neighbours in the Russian steppe: Turks, Khazars and Qipchaqs, Ashgate/Variorum, 2003. "Tenth-century Byzantine sources, speaking in cultural more than ethnic terms, acknowledged a wide zone of diffusion by referring to the Khazar lands as 'Eastern Tourkia' and Hungary as 'Western Tourkia.'" Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in the World History, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 51, citing Peter B. Golden, 'Imperial Ideology and the Sources of Political Unity Amongst the Pre-Činggisid Nomads of Western Eurasia,' Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 2 (1982), 37–76.

- ^ Carter V. Findley, The Turks in world history, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 51

- ^ Golden 2001a, pp. 28–29, 37.

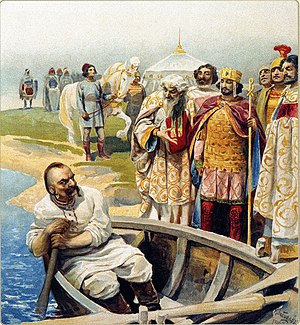

- ^ From Klavdiy Lebedev (1852–1916), Svyatoslav's meeting with Emperor John, as described by Leo the Deacon.

- ^ Brook 2009, ch. 5

- ^ Kovalev, "Creating Khazar Identity" 220-253.

- ^ G. Hosszú: Proposal for encoding the Khazarian Rovas script in the SMP of the UCS. National Body Contribution for consideration by UTC and ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2, January 21st, 2011, revised: May 19th, 2011, Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3999, http://std.dkuug.dk/jtc1/sc2/wg2/docs/n3999.pdf