Neapolitan language: Difference between revisions

m →Neapolitan Grammar: redirects go to this article so removing |

|||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

== Neapolitan Grammar == |

== Neapolitan Grammar == |

||

<BR> |

|||

*[[Neapolitan articles]] |

|||

'''Neapolitan Alphabet and Pronunciation'''<BR> |

|||

<!--removing as these are red links, but these need not be separate articles, they could be sections in this article |

|||

The Neapolitan alphabet is almost the same as our English alphabet except that it consists of only 22 letters. It does not contain ''k,'' ''w,'' ''x,'' or ''y'' even though these letters might be found in some foreign words. The pronunciation guidelines that follow are based on pronunciation of American English and these values may or may not be applicable to British English.<BR><BR> |

|||

*[[Neapolitan nouns and adjectives]] |

|||

Although Neapolitan is closely related to Italian, the official national language of Italy, there are some differences in pronunciation often rendering certain words or phrases in Neapolitan unrecognizable to other, non-Neapolitan Italians. The most notable of this is the indistinct pronunciation of the final vowel and other vowels when unstressed. All stressed (accented) vowels, however, are pronounced distinctly, even when they are the final vowel. This indistinct pronunciation manifests itself as the sound of the ''schwa'' which is pronounced like the ''a'' in ''about'' or the ''u'' in ''upon''.<BR> |

|||

*[[Neapolitan pronouns]] |

|||

*[[Neapolitan verbs]] |

|||

'''Vowels''' <BR> |

|||

*[[Neapolitan prepositions]]--> |

|||

While there are only 5 graphic vowels in Neapolitan, phonetically, there are 7 (or 8 when we include the ''schwa''). The vowels ''e'' and ''o'' can be either "closed" or "open" and the pronounciation is different for the two. The grave accent (à, è, ò) is used to denote open vowels, and the acute accent (é, í, ó, ú) is used to denote closed vowels. However, accent marks are not used in the actual spelling of words except when they occur on the final syllable of a word, such as ''Totò, arrivà,'' or ''pecché'' and when they appear here in other positions it is only to demonstrate where the stress, or accent, falls in some words.<BR><BR> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Letter |

|||

! Pronunciation Guide |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''a'' |

|||

| ''a'' is always open and is pronounced like the ''a'' in ''father'' except that when it is the final, unstressed vowel, its pronunciation is indistinct and approaches the sound of the schwa |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''e'' |

|||

| stressed, open ''e'' is pronounced like the ''a'' in ''after''<BR> stressed, closed ''e'' is pronounced like the ''a'' in ''fame'' except that it does not die off into ''ee''<BR> unstressed ''e'' is pronounced as a ''schwa'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''i'' |

|||

| ''i'' is always closed and is pronounced like the ''ee'' in ''meet'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''o'' |

|||

| stressed, open ''o'' is pronounced like the ''o'' in ''often''<BR> stressed, closed ''o'' is pronounced like the ''o'' in ''closed'' except that it does not die off into ''oo'' <BR> unstressed ''o'' is pronounced as a ''schwa'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''u'' |

|||

| ''u'' is always closed and is pronounced like the ''oo'' in ''boot'' |

|||

|} |

|||

<BR> |

|||

'''Consonants''' <BR> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Letter |

|||

! Pronunciation Guide |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''b'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''c'' |

|||

| when followed by ''e'' or ''i'' the pronunciation is somewhere between the ''sh'' in ''share'' and the ''ch'' in ''chore'' and otherwise is like the ''c'' in ''coal'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''d'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''f'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''g'' |

|||

| when followed by ''e'' or ''i'' the pronunciation is somewhere between the ''g'' of ''germane'' and the ''z'' of ''azure'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''h'' |

|||

| ''h'' is always silent and is only used to differentiate words pronounced the same and otherwise spelled alike (''e.g. a, ha; anno, hanno'') and after ''g'' or ''c'' to preserve the hard sound when ''e'' or ''i'' follows (''e.g. ce, che; gi, ghi) |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''j'' |

|||

| referred to as a semi-consonant, is pronounced like English ''y'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''l'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''m'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''n'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''p'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''q'' |

|||

| always followed by ''u'' and pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''r'' |

|||

| when between two vowels it is sounds very much like the English ''d'' but in reality it is a single tic of a trilled ''r''; when at the beginning of a word or when preceded by or followed by another consonant, it is trilled. |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''s'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English and just like in English it is sometimes voiced and sometimes unvoiced |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''t'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''v'' |

|||

| pronounced the same as in English |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''z'' |

|||

| voiced ''z'' is pronounced like the ''ds'' in ''suds'' while unvoiced ''z'' is pronounced like the ''ts'' in ''jetsam'' |

|||

|} |

|||

<BR><BR> |

|||

'''The Definite Article'''<BR> |

|||

Basically, the Neapolitan definite articles, corresponding to the English "the," are ''La'' (feminine singular), ''Lo'' (masculine singular) and ''Li'' (plural for both), but in reality these forms will probably only be found in older literature, of which there is much to be found. Modern Neapolitan uses, almost entirely, shortened forms of these articles which are: |

|||

Before a word beginning with a consonant: |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

! |

|||

! Singular |

|||

! Plural |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''Masculine''' |

|||

| ''’o'' |

|||

| ''’e'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''Feminine''' |

|||

| ''’a'' |

|||

| ''’e'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''Neuter''' |

|||

| ''’o'' |

|||

| - |

|||

|} |

|||

Before a word beginning with a vowel: |

|||

''l’'' or ''ll’'' for both masculine and feminine; for both singular and plural. |

|||

Although both forms can be found, the ''ll’'' form is by far the most common. |

|||

It is well to note that in Neapolitan the gender of a noun is not easily determined by the article, so other means must be used. In the case of ''’o'' which can be either masculine singular or neuter singular (there is no neuter plural in Neapolitan), when it is neuter gender the intial consonant of the noun is doubled. As an example, the name of a language in Neapolitan is always neuter gender, so if we see ''’o nnapulitano'' we know it refers to the Neapolitan language, whereas ''’o napulitano'' would refer to a Neapolitan man. |

|||

Likewise, since ''’e'' can be either masculine plural or feminine plural, when it is feminine plural, the initial consonant of the noun is doubled. As an example, let's consider ''’a lista'' which in Neapolitan is feminine singular for "list." In the plural it becomes ''’e lliste''. |

|||

There can also be problems with nouns whose singular form ends in ''e''. Since plural nouns usually end in ''e'' whether masculine or feminine, the masculine plural is often formed by orthographically changing the spelling. As an example, let's consider the word ''guaglione'' (which means "boy", or "girl" in the feminine form): |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

! |

|||

! Singular |

|||

! Plural |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''Masculine''' |

|||

| ''’o guaglione'' |

|||

| ''’e guagliune'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''Feminine''' |

|||

| ''’a guagliona'' |

|||

| ''’e gguaglione'' |

|||

|} |

|||

More will be said about these orthographically changing nouns in the section on Neapolitan Nouns. |

|||

A couple of notes about consonant doubling: |

|||

1. Doubling is a function of the article (and certain other words), and these same words may be seen in other contexts without the consonant doubled. More will be said about this in the section on consonant doubling. |

|||

2. Doubling only occurs when the consonant is followed by a vowel. If it is followed by another consonant, such as in the word ''spagnuolo (Spanish)'', no doubling occurs. |

|||

'''The Indefinite Article''' |

|||

The Neapolitan indefinite articles, corresponding to the English "a" or "an," are presented in the following table: |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

! |

|||

! Masculine |

|||

! Feminine |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''Before words beginning with a consonant''' |

|||

| ''nu'' |

|||

| ''na'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''Before words beginning with a vowel''' |

|||

| ''n’'' |

|||

| ''n’'' |

|||

|} |

|||

'''Doubled Initial Consonants''' <BR> |

|||

In Neapolitan, many times the initial consonant of a word is doubled. This is apparent both in written as well as spoken Neapolitan. <BR> |

|||

* All feminine plural nouns, when preceded by the freminine plural definite article, ''’e,'' or by any feminine plural adjective, will have the initial consonant doubled.<BR> |

|||

* All neuter singular nouns, when preceded by the neuter singular definite article, ''’o,'' or by a neuter singular adjective, will have the initial consonant doubled.<BR> |

|||

* In addition, other words also trigger this doubling. Below is a list of words which trigger the doubling of the initial consonant of the word which follows.<BR> |

|||

Bear in mind, however, that when there is a pause after the "trigger" word, then the doubling does not occur (e.g. ''Tu sî gguaglione, [You are a boy]'' where ''sî'' is a "trigger" word causing doubling of the initial consonant in ''guaglione'' but in the phrase ''’A do sî, guagliò? [Where are you from, boy?'' no doubling occurs). It is also well to note that no doubling occurs when the initial consonant is followed by another consonant (e.g. ''’o ttaliano [the Italian language], but ’o spagnuolo [the Spanish language], where ''’o is the neuter definite article).<BR> |

|||

'''Words which trigger doubling'''<BR> |

|||

* The conjunctions '''''e''''' and '''''né''''', but not '''''o''''' (e.g. ''pane e ccaso''; ''né ppane né ccaso''; but ''pane o caso''. |

|||

* The prepositions '''''a''''', '''''pe''''', '''''cu''''' (e.g. ''a mme''; ''pe tte''; ''cu vvuje'') |

|||

* The negation '''''nu''''', short for ''nun/nunn'' (e.g. ''nu ddicere niente'') |

|||

* The indefinites '''''ogne''''', '''''quacche''''' (e.g. ''ogne ccasa''; ''quacche ccosa'' |

|||

* Interrogative '''''che''''' and relative '''''che''''', but not '''''ca''''' (e.g. ''Che ppiensa?'' ''Che ffemmena!'' ''Che ccapa!'') |

|||

* '''''accussí''''' (e.g. ''accussí ttuosto'') |

|||

* From the verb "essere," '''''so’'''''; '''''sî'''''; '''''è'''''; but not '''''songo''''' (e.g. ''io so’ ppazzo''; ''tu sî ffesso''; ''chillo è ccafone''; ''chilli so’ ccafune''; but ''chilli songo cafune'') |

|||

* '''''cchiú''''' (e.g. ''cchiú ppoco'') |

|||

* The number '''''tre''''' (e.g. ''tre ssegge'') |

|||

* The neuter definite article '''''’o''''' (e.g. ’o ppane, but ''nu poco ’e pane) |

|||

* The neuter pronoun '''''’o''''' (e.g. ''’o ttiene ’o ppane?'') |

|||

* Demonstrative adjectives '''''chestu''''' and '''''chellu''''' which refer to neuter nouns (e.g. ''chestu ffierro''; ''chellu ppane'') |

|||

* The feminine plural definite article '''''’e''''' (e.g. ''’e ssegge''; ''’e gguaglione'') |

|||

* the plural pronoun, both masculine and feminine, '''''’e''''' (''’e gguaglione ’e cchiamme tu?'') |

|||

* The locative '''''lloco''''' (e.g. ''lloco ssotto'') |

|||

* From the verb ''stà'': '''''sto’''''' (e.g. ''sto’ pparlanno'') |

|||

* From the verb ''puté'': '''''può'''''; '''''pô''''' (e.g. ; ''isso pô ssapé'') |

|||

* The religious titles '''''padre''''' and '''''madre''''' (e.g. ''padre Ccarlo''; ''padre Mmichele'') |

|||

* Special case '''''Spiritu Ssanto''''' |

|||

'''References'''<BR> |

|||

''’A lengua ’e Pulecenella'' by Carlo Iandolo <BR> |

|||

''Il napoletano parlato e scritto'' by Nicola De Blasi and Luigi Imperatore |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 17:26, 6 June 2009

| Neapolitan | |

|---|---|

| Nnapulitano | |

| Native to | |

Native speakers | 7.5 million |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | nap |

| ISO 639-3 | nap |

| |

Neapolitan (autonym: napulitano; Italian: napoletano) is the language of the city and region of Naples, Campania (Neapolitan: Nàpule, Italian: Napoli). On October 14, 2008 the Neapolitan language was accepted by a law by the Region of Campania.[5]

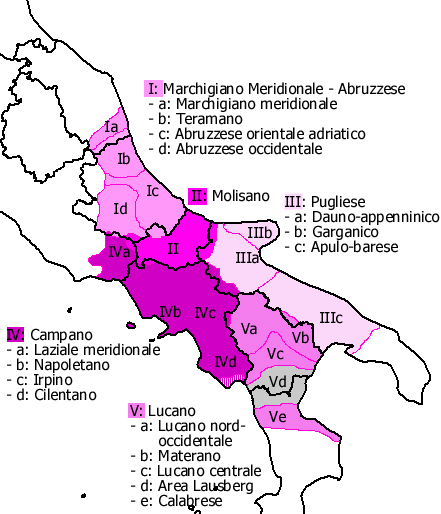

The name is often given to the varied Italo-Western group of dialects of southern Italy; for example Ethnologue groups the dialects as a separate Romance language called Napoletano-Calabrese.[6] This linguistic group is spoken throughout most of southern continental Italy, including the Gaeta and Sora districts of southern Lazio, the southern part of Marche and Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, northern Calabria, and northern and central Puglia. As of 1976, there were 7,047,399 theoretical native speakers of this group of dialects.[6]

Distribution

Many would argue that the term "Neapolitan" should only be used for the dialect of Naples and its vicinity (as spoken around Naples and the Bay of Naples, Caserta, Avellino, and Salerno).

Neapolitan, as the varied Italo-Western group of dialects, is distributed throughout most of continental southern Italy, historically united during the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The many dialects of this linguistic group include Neapolitan proper, Irpino, Cilentano, Ascolano, Teramano, Abruzzese Orientale Adriatico, Abruzzese Occidentale, Molisano, Dauno-Appenninico, Garganico, Apulo-Barese, Lucano, and Cosentino. The dialects are part of a strong and varied continuum, so the various dialects in southern Lazio, Marche, Abruzzo, Molise, Apulia, Lucania and Calabria can typically be recognizable as regional groups of dialects. In eastern Abruzzo and Lazio the dialects give way to Central Italian dialects such as Romanesco. In central Calabria and southern Puglia, the dialects give way to Sicilian dialects. Largely due to massive southern Italian immigration in the 20th century, there are also numbers of speakers in Italian diaspora communities in the United States, Canada, Australia, Brazil and Argentina.

Neapolitan has also had a significant influence on the intonation of Rioplatense Spanish, spoken mainly in the Buenos Aires region of Argentina.[7]

The Language

Neapolitan is generally considered as Italo-Dalmatian. There are notable differences among the various dialects, but they are all generally mutually intelligible. The language as a whole has often fallen victim of its status as a "language without prestige".

Standard Italian and Neapolitan are of variable mutual comprehensibility, depending on factors both affective and linguistic. There are notable grammatical differences such as nouns in the neuter form and unique plural formation, and historical phonological developments often render the cognacy of lexical items opaque. Its evolution has been similar to that of Italian and other Romance languages from their roots in Spoken Latin. It has also developed with a pre-Latin Oscan influence, which controversially purported to be noticeable in the pronunciation of the d sound as an r sound (rhotacism), but only when "d" is at the beginning of a word, or between two vowels (e.g.- "doje" or "duje" (two, respectively feminine and masculine form), pronounced, and often spelled, as "roje"/"ruje", vedé (to see), pronounced as "veré", and often spelled so, same for cadé/caré (to fall), and Madonna/Maronna). Some think that the rhotacism is a more recent phenomenon, though. Another purported Oscan influence (claimed by some to be more likely than the previous one) is historical assimilation of the consonant cluster /nd/ as /nn/, pronounced [nː] (this generally is reflected in spelling more consistently) (e.g.- "munno" ('world', compare to Italian "mondo"), "quanno" ('when', compare to Italian "quando"), etc.), along with the development of /mb/ as /mm/ (e.g.- tammuro (drum), cfr. Italian tamburo), also consistently reflected in spelling. Other effects of the Oscan substratum are postulated too, although substratum claims are highly controversial. In addition, the language was also affected by the Greek language. Naples was largely Greek-speaking prior to the eighth century C.E., and the Greek language remained dominant in much of Southern Italy for many further centuries before finally being fully supplanted by Italian dialects (see: Griko language for remnant traces of Greek on the Italian peninsula). There have never been any successful attempts to standardize the language (e.g.- consulting three different dictionaries, one finds three different spellings for the word for tree, arbero, arvero and àvaro).

Neapolitan has enjoyed a rich literary, musical and theatrical history (notably Giambattista Basile, Eduardo de Filippo, Salvatore di Giacomo and Totò). Thanks to this heritage and the musical work of Renato Carosone in the 1950s, Neapolitan is still in use in popular music, even gaining national popularity in the songs of Pino Daniele and the Nuova Compagnia di Canto Popolare.

The language has no official status within Italy and is not taught in schools. The Università Federico II in Naples offers (from 2003) courses in Campanian Dialectology at the faculty of Sociology, whose actual aim is not teaching students to speak the language, but studying its history, usage, literature and social role. There are also ongoing legislative attempts at the national level to have it recognized as an official minority language of Italy. It is however a recognized ISO 639 Joint Advisory Committee language with the language code of nap.

For comparison, The Lord's Prayer is here reproduced in the Neapolitan spoken in Naples and in a northern Calabrian dialect, in contrast with a variety of southern Calabrian (part of Sicilian language), Italian and Latin.

| Neapolitan (Naples) | Neapolitan (Northern Calabrian) | Sicilian (Southern Calabrian) | Sicilian (Sicily) | Italian | Latin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pate nuoste ca staje 'ncielo, | Patre nuorru chi sta ntru cielu, | Patri nostru chi' sini nt'o celu, | Nunnu nostru, ca inta lu celu siti | Padre Nostro, che sei nei cieli, | Pater noster, qui es in caelis |

| santificammo 'o nomme tuojo | chi sia santificatu u nume tuoio, | m'esti santificatu u nomi toi, | mu santificatu esti lu nomu vostru: | sia santificato il tuo nome. | sanctificetur nomen tuum: |

| faje vení 'o regno tuojo, | venisse u riegnu tuoio, | Mù veni u rregnu toi, | Mu veni lu regnu vostru. | Venga il tuo regno, | Adveniat regnum tuum. |

| sempe c' 'a vuluntà toja, | se facisse a vuluntà tuoia, | ù si facissi a voluntà | Mu si faci la vuluntati vostra | sia fatta la tua volontà, | Fiat voluntas tua |

| accussí 'ncielo e 'nterra. | sia nto cielu ca nterra. | com'esti nt'o celu, u stessa sup'a terra. | comu esti inta lu celu, accussì incapu la terra | come in cielo, così in terra. | sicut in caelo et in terra |

| Fance avé 'o ppane tutt' 'e juorne | Ranne oje u pane nuorro e tutti i juorni, | Dùnandi ped oji u pani nostru e tutti i jorna | Dunàtini ogghi lu nostru panuzzu. | Dacci oggi il nostro pane quotidiano, | Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie. |

| lièvace 'e dièbbete | perdunacce i rebita nuorri, | e' perdùnandi i debiti, | E pirdunàtini li nostri dèbbiti, | e rimetti a noi i nostri debiti, | Et dimitte nobis debita nostra, |

| comme nuje 'e llevamme a ll'ate, | cumu nue perdunammu i rebituri nuorri. | comu nù nc'i perdunamu ad i debituri nostri. | comu nuautri li pirdunamu a li nostri dibbitura. | come noi li rimettiamo ai nostri debitori. | sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. |

| nun 'nce fa spantecà, | Un ce mannare ntra tentazione, | Non nci dassari nt'a tentazioni, | E nun lassàtini cascari inta la tintazziuni; | E non ci indurre in tentazione, | Et ne nos inducas in temptationem; |

| e llievace 'o mmale 'a tuorno. | ma liberacce e ru male. | ma liberandi d'o mali | ma scanzàtini di lu mali. | ma liberaci dal male. | sed libera nos a malo. |

| Ammèn. | Ammèn. | Ammèn. | Ammèn. | Amen. | Amen. |

Neapolitan Grammar

Neapolitan Alphabet and Pronunciation

The Neapolitan alphabet is almost the same as our English alphabet except that it consists of only 22 letters. It does not contain k, w, x, or y even though these letters might be found in some foreign words. The pronunciation guidelines that follow are based on pronunciation of American English and these values may or may not be applicable to British English.

Although Neapolitan is closely related to Italian, the official national language of Italy, there are some differences in pronunciation often rendering certain words or phrases in Neapolitan unrecognizable to other, non-Neapolitan Italians. The most notable of this is the indistinct pronunciation of the final vowel and other vowels when unstressed. All stressed (accented) vowels, however, are pronounced distinctly, even when they are the final vowel. This indistinct pronunciation manifests itself as the sound of the schwa which is pronounced like the a in about or the u in upon.

Vowels

While there are only 5 graphic vowels in Neapolitan, phonetically, there are 7 (or 8 when we include the schwa). The vowels e and o can be either "closed" or "open" and the pronounciation is different for the two. The grave accent (à, è, ò) is used to denote open vowels, and the acute accent (é, í, ó, ú) is used to denote closed vowels. However, accent marks are not used in the actual spelling of words except when they occur on the final syllable of a word, such as Totò, arrivà, or pecché and when they appear here in other positions it is only to demonstrate where the stress, or accent, falls in some words.

| Letter | Pronunciation Guide |

|---|---|

| a | a is always open and is pronounced like the a in father except that when it is the final, unstressed vowel, its pronunciation is indistinct and approaches the sound of the schwa |

| e | stressed, open e is pronounced like the a in after stressed, closed e is pronounced like the a in fame except that it does not die off into ee unstressed e is pronounced as a schwa |

| i | i is always closed and is pronounced like the ee in meet |

| o | stressed, open o is pronounced like the o in often stressed, closed o is pronounced like the o in closed except that it does not die off into oo unstressed o is pronounced as a schwa |

| u | u is always closed and is pronounced like the oo in boot |

Consonants

| Letter | Pronunciation Guide |

|---|---|

| b | pronounced the same as in English |

| c | when followed by e or i the pronunciation is somewhere between the sh in share and the ch in chore and otherwise is like the c in coal |

| d | pronounced the same as in English |

| f | pronounced the same as in English |

| g | when followed by e or i the pronunciation is somewhere between the g of germane and the z of azure |

| h | h is always silent and is only used to differentiate words pronounced the same and otherwise spelled alike (e.g. a, ha; anno, hanno) and after g or c to preserve the hard sound when e or i follows (e.g. ce, che; gi, ghi) |

| j | referred to as a semi-consonant, is pronounced like English y |

| l | pronounced the same as in English |

| m | pronounced the same as in English |

| n | pronounced the same as in English |

| p | pronounced the same as in English |

| q | always followed by u and pronounced the same as in English |

| r | when between two vowels it is sounds very much like the English d but in reality it is a single tic of a trilled r; when at the beginning of a word or when preceded by or followed by another consonant, it is trilled. |

| s | pronounced the same as in English and just like in English it is sometimes voiced and sometimes unvoiced |

| t | pronounced the same as in English |

| v | pronounced the same as in English |

| z | voiced z is pronounced like the ds in suds while unvoiced z is pronounced like the ts in jetsam |

The Definite Article

Basically, the Neapolitan definite articles, corresponding to the English "the," are La (feminine singular), Lo (masculine singular) and Li (plural for both), but in reality these forms will probably only be found in older literature, of which there is much to be found. Modern Neapolitan uses, almost entirely, shortened forms of these articles which are:

Before a word beginning with a consonant:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Masculine | ’o | ’e |

| Feminine | ’a | ’e |

| Neuter | ’o | - |

Before a word beginning with a vowel:

l’ or ll’ for both masculine and feminine; for both singular and plural.

Although both forms can be found, the ll’ form is by far the most common.

It is well to note that in Neapolitan the gender of a noun is not easily determined by the article, so other means must be used. In the case of ’o which can be either masculine singular or neuter singular (there is no neuter plural in Neapolitan), when it is neuter gender the intial consonant of the noun is doubled. As an example, the name of a language in Neapolitan is always neuter gender, so if we see ’o nnapulitano we know it refers to the Neapolitan language, whereas ’o napulitano would refer to a Neapolitan man.

Likewise, since ’e can be either masculine plural or feminine plural, when it is feminine plural, the initial consonant of the noun is doubled. As an example, let's consider ’a lista which in Neapolitan is feminine singular for "list." In the plural it becomes ’e lliste.

There can also be problems with nouns whose singular form ends in e. Since plural nouns usually end in e whether masculine or feminine, the masculine plural is often formed by orthographically changing the spelling. As an example, let's consider the word guaglione (which means "boy", or "girl" in the feminine form):

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Masculine | ’o guaglione | ’e guagliune |

| Feminine | ’a guagliona | ’e gguaglione |

More will be said about these orthographically changing nouns in the section on Neapolitan Nouns.

A couple of notes about consonant doubling:

1. Doubling is a function of the article (and certain other words), and these same words may be seen in other contexts without the consonant doubled. More will be said about this in the section on consonant doubling.

2. Doubling only occurs when the consonant is followed by a vowel. If it is followed by another consonant, such as in the word spagnuolo (Spanish), no doubling occurs.

The Indefinite Article

The Neapolitan indefinite articles, corresponding to the English "a" or "an," are presented in the following table:

| Masculine | Feminine | |

|---|---|---|

| Before words beginning with a consonant | nu | na |

| Before words beginning with a vowel | n’ | n’ |

Doubled Initial Consonants

In Neapolitan, many times the initial consonant of a word is doubled. This is apparent both in written as well as spoken Neapolitan.

- All feminine plural nouns, when preceded by the freminine plural definite article, ’e, or by any feminine plural adjective, will have the initial consonant doubled.

- All neuter singular nouns, when preceded by the neuter singular definite article, ’o, or by a neuter singular adjective, will have the initial consonant doubled.

- In addition, other words also trigger this doubling. Below is a list of words which trigger the doubling of the initial consonant of the word which follows.

Bear in mind, however, that when there is a pause after the "trigger" word, then the doubling does not occur (e.g. Tu sî gguaglione, [You are a boy] where sî is a "trigger" word causing doubling of the initial consonant in guaglione but in the phrase ’A do sî, guagliò? [Where are you from, boy? no doubling occurs). It is also well to note that no doubling occurs when the initial consonant is followed by another consonant (e.g. ’o ttaliano [the Italian language], but ’o spagnuolo [the Spanish language], where ’o is the neuter definite article).

Words which trigger doubling

- The conjunctions e and né, but not o (e.g. pane e ccaso; né ppane né ccaso; but pane o caso.

- The prepositions a, pe, cu (e.g. a mme; pe tte; cu vvuje)

- The negation nu, short for nun/nunn (e.g. nu ddicere niente)

- The indefinites ogne, quacche (e.g. ogne ccasa; quacche ccosa

- Interrogative che and relative che, but not ca (e.g. Che ppiensa? Che ffemmena! Che ccapa!)

- accussí (e.g. accussí ttuosto)

- From the verb "essere," so’; sî; è; but not songo (e.g. io so’ ppazzo; tu sî ffesso; chillo è ccafone; chilli so’ ccafune; but chilli songo cafune)

- cchiú (e.g. cchiú ppoco)

- The number tre (e.g. tre ssegge)

- The neuter definite article ’o (e.g. ’o ppane, but nu poco ’e pane)

- The neuter pronoun ’o (e.g. ’o ttiene ’o ppane?)

- Demonstrative adjectives chestu and chellu which refer to neuter nouns (e.g. chestu ffierro; chellu ppane)

- The feminine plural definite article ’e (e.g. ’e ssegge; ’e gguaglione)

- the plural pronoun, both masculine and feminine, ’e (’e gguaglione ’e cchiamme tu?)

- The locative lloco (e.g. lloco ssotto)

- From the verb stà: sto’ (e.g. sto’ pparlanno)

- From the verb puté: può; pô (e.g. ; isso pô ssapé)

- The religious titles padre and madre (e.g. padre Ccarlo; padre Mmichele)

- Special case Spiritu Ssanto

References

’A lengua ’e Pulecenella by Carlo Iandolo

Il napoletano parlato e scritto by Nicola De Blasi and Luigi Imperatore

See also

External links

- On line English - Neapolitan translation

- Websters Online Dictionary Neapolitan/English

- Ethnologue World linguistic classification

- Neapolitan language introduction

- Interactive Map of languages in Italy

- Neapolitan on-line radio station

- Neapolitan glossary on Wiktionary

- Italian-Neapolitan searchable online dictionary

- Grammar primer and extensive vocabulary for the Neapolitan dialect of Torre del Greco

- French-Neapolitan downloadable and searchable online dictionary

- Neapolitan Wikiprimer

- Neapolitan language and culture (in Italian)

References

- ^ Ali, Linguistic atlas of Italy

- ^ Linguistic cartography of Italy by Padova University

- ^ Italiand dialects by Pellegrini

- ^ AIS, Sprach-und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz, Zofingen 1928-1940

- ^ Article in Italian language of Il Denaro

- ^ a b Ethnologue Napoletano-Calabrese

- ^ http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract;jsessionid=43F6CF4CEB6223AA2ED40C7926999F70.tomcat1?fromPage=online&aid=236145