Valerie Solanas: Difference between revisions

Ongepotchket (talk | contribs) m removed Category:Sex segregation using HotCat |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead.) #IABot (v2.0.9.5) (Hey man im josh - 20898 |

||

| (604 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American radical feminist (1936–1988)}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=September 2012}} |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{Infobox writer |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=June 2023}} |

|||

| name = Valerie Solanas |

|||

{{Infobox person |

|||

| image = Valerie Solanas.jpg |

|||

| name = Valerie Solanas |

|||

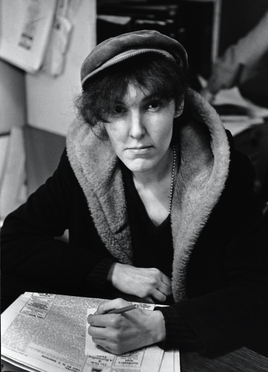

| caption = Solanas at the ''Village Voice'' offices, February 1967 |

|||

| image = Valerie Solanas by Fred W. McDarrah.jpg |

|||

| caption = Solanas in the ''[[Village Voice]]'' newsroom, 1967, by [[Fred W. McDarrah]] |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1936|4|9}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Ventnor City, New Jersey]], U.S. |

|||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1988|4|25|1936|4|9}} |

|||

| death_place = [[San Francisco, California]], U.S. |

|||

| occupation = Writer |

|||

| education = [[University of Maryland, College Park]], [[University of Minnesota]], [[University of California, Berkeley]] |

|||

| children = 1 |

|||

| movement = [[Radical feminism]] |

|||

| signature = Solanas-signature.png |

|||

| module = {{Infobox writer |

|||

|embed = yes |

|||

| pseudonym = |

| pseudonym = |

||

| birth_name = Valerie Jean Solanas |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1936|4|9}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Ventnor City, New Jersey]], U.S. |

|||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1988|4|25|1936|4|9}} |

|||

| death_place = [[San Francisco]], California, U.S. |

|||

| occupation = Writer |

|||

| nationality = [[American nationality law|American]] |

|||

| ethnicity = |

| ethnicity = |

||

| citizenship = |

|||

| period = |

| period = |

||

| genre = |

| genre = |

||

| subject = Radical feminism |

| subject = [[Radical feminism]] |

||

| notableworks = {{ubl|''[[SCUM Manifesto]]'' (1967)|''[[Up Your Ass (play)|Up Your Ass]]'', a play (wr. 1965, prem. 2000, publ. 2014)}} |

|||

| movement = [[Radical feminism]] |

|||

| notableworks = ''[[SCUM Manifesto]]'' (1967) |

|||

| spouse = |

| spouse = |

||

| partner = |

| partner = |

||

| children = David Blackwell |

|||

| relatives = |

| relatives = |

||

| influences = |

| influences = |

||

| influenced = |

| influenced = |

||

| awards = |

| awards = |

||

| signature = Solanas-signature.png |

|||

| website = |

| website = |

||

| portaldisp = |

| portaldisp = |

||

}} |

|||

| criminal_charges = [[Attempted murder]], assault, [[Gun law in the United States|illegal possession of a gun]], [[Plea deal|plead to]] reckless assault with intent to harm |

|||

| criminal_penalty = 3 years' incarceration |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Valerie Jean Solanas''' (April 9, 1936 – April 25, 1988) was an American [[radical feminism|radical feminist]] |

'''Valerie Jean Solanas''' (April 9, 1936 – April 25, 1988) was an American [[radical feminism|radical feminist]] known for the ''[[SCUM Manifesto]]'', which she self-published in 1967, and her attempt to murder artist [[Andy Warhol]] in 1968. |

||

On June 3, 1968, Solanas went to [[The Factory]], shot Warhol and art critic [[Mario Amaya]], and attempted to shoot Warhol's manager, [[Frederick W. Hughes|Fred Hughes]]. Solanas was charged with [[attempted murder]], assault, and illegal possession of a firearm. After her release, she continued to promote the ''SCUM Manifesto''. She died in 1988 of [[pneumonia]] in San Francisco. |

|||

She was born in New Jersey and as a teenager had a volatile relationship with her mother and stepfather after her parents' divorce. As a consequence, she was sent to live with her grandparents. Her alcoholic grandfather physically abused her and Solanas ran away and became homeless. She [[coming out|came out]] as a lesbian in the 1950s. She graduated with a degree in [[psychology]] from the [[University of Maryland, College Park]]. Solanas relocated to [[Berkeley, California]]. There, she began writing her most notable work, the ''[[SCUM Manifesto]]'', which urged women to "overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex."<ref>{{harvp|Solanas|1967|p=1}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|DeMonte|2010|p=178}}</ref> |

|||

== Early life == |

|||

Solanas moved to New York City in the mid-1960s, working as a writer. She met Andy Warhol and asked Warhol to produce her play, ''Up Your Ass''. She gave him her script, which she later accused him of losing and/or stealing, followed by Warhol expressing additional indifference to her play. After Solanas demanded financial compensation for the lost script, Warhol hired her to perform in his film, ''[[I, a Man]]'', paying her $25. |

|||

Valerie Solanas was born in 1936 in [[Ventnor City, New Jersey]], to Louis Solanas and Dorothy Marie Biondo.<ref>State of California. California Death Index, 1940–1997. Sacramento, CA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics.</ref><ref>{{harvp|Violet|1990|p=184}}</ref><ref name=Lord>{{harvp|Lord|2010}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Harron|1996|p=xi}}</ref> Her father was a bartender and her mother a dental assistant.<ref name=Lord/><ref name="Fahs_3">{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=3}}</ref> She had a younger sister, Judith Arlene Solanas Martinez.<ref>{{harvp|Jansen|2011|p=141}}</ref> Her father was born in [[Montreal]], Quebec, Canada, to parents who immigrated from Spain. Her mother was an Italian-American of [[Genoa]]n and [[Sicilian Americans|Sicilian]] descent born in [[Philadelphia]].<ref name="Fahs_3"/> |

|||

Solanas reported that her father regularly [[child sexual abuse|sexually abused]] her.<ref name=Watson35>{{harvp|Watson|2003|pp=35–36}}</ref> Her parents divorced when she was young, and her mother remarried shortly afterwards.<ref>{{harvp|Solanas|1996|p=48}}</ref> Solanas disliked her stepfather and began rebelling against her mother, becoming a [[truancy|truant]]. As a child, she wrote insults for children to use on one another, for the cost of a dime. She beat up a girl in high school who was bothering a younger boy, and also hit a [[nun]].<ref name=Lord/> |

|||

In 1967, Solanas began self-publishing the ''SCUM Manifesto''. Olympia Press owner [[Maurice Girodias]] offered to publish Solanas' future writings, and she understood the contract to mean that Girodias would own her writing. Convinced that Girodias and Warhol were conspiring to steal her work, Solanas purchased a gun in the spring of 1968. |

|||

Because of her rebellious behavior, Solanas' mother sent her to be raised by her grandparents in 1949. Solanas reported that her grandfather was a violent alcoholic who often beat her. When she was aged 15, she left her grandparents and became homeless.<ref>{{harvp|Buchanan|2011|p=132}}</ref> In 1953, Solanas gave birth to a son, fathered by a married sailor.<ref>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|pp=23–24}}</ref>{{Efn|Solanas's cousin claimed the man was a sailor, and that she may have also given birth to a second child before leaving home.<ref name=Fahs2008>{{harvp|Fahs|2008}}</ref>}} The child, named David, was taken away and she never saw him again.<ref name="Coburn">{{cite web|first=Judith|last=Coburn|date=January 11, 2000|title=Solanas Lost and Found|work=[[The Village Voice]]|url=http://www.villagevoice.com/2000-01-11/news/solanas-lost-and-found/|access-date=November 27, 2011|archive-date=October 13, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121013095242/http://www.villagevoice.com/2000-01-11/news/solanas-lost-and-found/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="Jobey">{{cite news|first=Liz|last=Jobey, Liz|title=Solanas and Son|newspaper=[[The Guardian]]|date=August 24, 1996}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Hewitt|2004|p=602}}</ref>{{Efn|Lord stated that Solanas and her son lived with "a middle-class military couple outside of Washington, D.C." before she went to the University of Maryland. This couple might have paid for her college tuition, according to Lord.<ref name=Lord/>}} |

|||

On June 3, 1968, she went to [[The Factory]], where she found Warhol. She shot at Warhol three times, with the first two shots missing and the final wounding Warhol. She also shot art critic [[Mario Amaya]], and attempted to shoot Warhol's manager, Fred Hughes, point blank, but the gun jammed. Solanas then turned herself in to the police. She was charged with attempted murder, assault, and illegal possession of a gun. She was diagnosed with [[paranoid schizophrenia]] and pleaded guilty to "reckless assault with intent to harm", serving a three-year prison sentence, including treatment in a mental hospital. After her release, she continued to promote the ''SCUM Manifesto''. She died in 1988 of [[pneumonia]], in San Francisco. |

|||

Despite this, Solanas graduated from high school on time and earned a degree in [[psychology]] from the [[University of Maryland, College Park]], where she was in the [[Psi Chi]] Honor Society.<ref name="HesfordDiedrich2010">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=154}}</ref><ref>Regarding the honor society: {{harvp|Jansen|2011|p=152}}</ref> While at the University of Maryland, she hosted a call-in radio show where she gave advice on how to combat men.<ref name=Watson35/> Solanas was an open lesbian, despite the conservative cultural climate of the 1950s.<ref name=Heller2001>{{harvp|Heller|2001}}</ref> |

|||

== Early life == |

|||

Solanas was born in [[Ventnor City, New Jersey]], to Louis Solanas and Dorothy Marie Biondo<ref>State of California. California Death Index, 1940–1997. Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics.</ref> in 1936.<ref>{{harvp|Violet|1990|p=184}}</ref><ref name=Lord>{{harvp|Lord|2010}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Harron|1996|p=xi}}</ref> Her father was a bartender and her mother, a dental assistant.<ref name=Lord/><ref name="Fahs_3">{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=3}}</ref> She had a younger sister, Judith Arlene Solanas Martinez.<ref>{{harvp|Jansen|2011|p=141}}</ref> Her father's parents were immigrants from Spain and her mother was Italian-American.<ref name="Fahs_3"/> |

|||

Solanas attended the [[University of Minnesota]]'s Graduate School of Psychology, where she worked in the animal research laboratory,<ref name="Nickels2005C">{{harvp|Nickels|2005|pp=15–16}}</ref> before dropping out and moving to attend [[University of California, Berkeley|Berkeley]] for a few courses. It was during this time that she began writing the ''SCUM Manifesto''.<ref name="Jobey"/> |

|||

Solanas said that she regularly suffered [[child sexual abuse|sexual abuse]] at the hands of her father.<ref name=Watson35>{{harvp|Watson|2003|pp=35–36}}</ref> Her parents divorced when she was young, and her mother remarried shortly afterwards.<ref>{{harvp|Solanas|1996|p=48}}</ref> Solanas disliked her stepfather and began rebelling against her mother, becoming a [[truancy|truant]]. As a child, she wrote insults for children to use on one another, for the cost of a dime. She beat up a boy in high school who was bothering a younger girl, and also hit a nun.<ref name=Lord/> Because of her rebellious behavior, her mother sent her to be raised by her grandparents in 1949. Solanas said that her grandfather was a violent alcoholic who often beat her. When she was 15, she left her grandparents and became [[homeless]].<ref>{{harvp|Buchanan|2011|p=132}}</ref> In 1953, she gave birth to a son, fathered by a married sailor.<ref>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|pp=23–24}}</ref>{{Efn|Solanas's cousin claimed the man was a sailor, and that Solanas may have also given birth to a second child before leaving home.<ref name=Fahs2008>{{harvp|Fahs|2008}}</ref>}} The child, named David (later David Blackwell by adoption), was taken away from Solanas and she never saw him again.<ref name="Coburn">{{Cite web|author=Judith Coburn|year=2000|title=Solanas Lost and Found|publisher=Village Voice|url=http://www.villagevoice.com/2000-01-11/news/solanas-lost-and-found/|accessdate= November 27, 2011}}</ref><ref name="Jobey">Jobey, Liz, ''Solanas and Son'', in ''[[The Guardian]]'', August 24, 1996</ref><ref>{{harvp|Hewitt|2004|p=602}}</ref>{{Efn|Lord stated that Solanas and her son lived with "a middle-class military couple outside of Washington, D.C." before she went to the University of Maryland. This couple might have paid for her college tuition, according to Lord.<ref name=Lord/>}} |

|||

== New York City and the Factory == |

|||

Despite this, she graduated from high school on time and earned a degree in [[psychology]] from the [[University of Maryland, College Park]], where she was in the [[Psi Chi]] Honor Society.<ref name="HesfordDiedrich2010">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=154}}</ref><ref>Regarding the honor society: {{harvp|Jansen|2011|p=152}}</ref> While at the University of Maryland, she hosted a call-in radio show where she gave advice on how to combat men.<ref name=Watson35/> She was also an open lesbian, despite the conservative cultural climate of the 1950s.<ref name=Heller2001>{{harvp|Heller|2001}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Warhol silver trunk 03.jpg|thumb|right|alt=silver painted trunk within a Plexiglas vitrine|This prop trunk, used in [[Andy Warhol]]'s Silver [[The Factory|Factory]], is where the copy of the "Up Your Ass" script Solanas gave Warhol was eventually found after Warhol's death in 1987.]] |

|||

In the mid-1960s, Solanas moved to New York City and supported herself through [[begging]] and [[Prostitution in the United States|prostitution]].<ref name=Heller2001/><ref name="Hamilton2002">{{harvp|Hamilton|2002|pp=264–}}</ref> In 1965 she wrote two works: an autobiographical<ref>{{harvp|Solanas|1968|p=89}}</ref> short story, "A Young Girl's Primer on How to Attain the Leisure Class",<!--Some sources title this work "A Young Girl's Primer or How to Attain the Leisure Class", but the original typed version uses "on", not "or".--> and a play, ''[[Up Your Ass (play)|Up Your Ass]]'',{{Efn|The original title of the work is ''Up Your Ass, or, From the Cradle to the Boat, or, The Big Suck, or, Up from the Slime.''<ref name=Lord/><ref name=Fahs2008/>}} about a young prostitute.<ref name=Heller2001/> According to James Martin Harding, the play is "based on a plot about a woman who 'is a man-hating hustler and panhandler' and who ... ends up killing a man."<ref name="CuttingPerfs-p168">{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=168}}</ref> Harding describes it as more a "provocation than ... a work of dramatic literature"<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=169}}</ref> and "rather adolescent and contrived."<ref name="CuttingPerfs-p168" /> The short story was published in [[Cavalier (magazine)|''Cavalier'' magazine]] in July 1966.<ref>{{harvp|Watson|2003|p=447}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Solanas |first=Valerie |title=For 2¢: pain |journal=[[Cavalier (magazine)|Cavalier]] |date=July 1966 |pages=38–40, 76–77}}</ref> ''Up Your Ass'' remained unpublished until 2014.<ref>{{cite book |last=Solanas |first=Valerie |date= March 31, 2014 |title=Up Your Ass |publisher=VandA.ePublishing |asin=B00JE6N2UG }}</ref> |

|||

She attended the [[University of Minnesota]]'s Graduate School of Psychology, where she worked in the psychology department's animal research laboratory,<ref name="Nickels2005C">{{harvp|Nickels|2005|pp=15–16}}</ref> before dropping out and moving to attend [[University of California, Berkeley|Berkeley]] for a few courses, when she began writing the ''[[SCUM Manifesto]]''.<ref name="Jobey"/> |

|||

== New York City and the Factory == |

|||

In the mid-1960s Solanas moved to New York City where she supported herself through [[begging]] and prostitution.<ref name=Heller2001/><ref name="Hamilton2002">{{harvp|Hamilton|2002|pp=264–}}</ref> In 1965 she wrote two works: an autobiographical<ref>{{harvp|Solanas|1968|p=89}}</ref> short story called "A Young Girl's Primer on How to Attain the Leisure Class"<!--Some sources title this work "A Young Girl's Primer or How to Attain the Leisure Class", but the original typed version uses "on", not "or".--> and a play titled ''Up Your Ass'',{{Efn|The original title of the work is ''Up Your Ass, or, From the Cradle to the Boat, or, The Big Suck, or, Up from the Slime.''<ref name=Lord/><ref name=Fahs2008/>}} about a young prostitute.<ref name=Heller2001/> According to James Martin Harding, the play is "based on a plot about a woman who 'is a man-hating hustler and panhandler' and who ... ends up killing a man"<ref name="CuttingPerfs-p168">{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=168}}</ref> and is more a "provocation than ... a work of dramatic literature"<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=169}}</ref> and "rather adolescent and contrived."<ref name="CuttingPerfs-p168" /> The short story was published in ''[[Cavalier (magazine)|Cavalier]]'' magazine in July 1966.<ref>{{harvp|Watson|2003|p=447}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Solanas |first=Valerie |title=For 2¢: pain |journal=[[Cavalier (magazine)|Cavalier]] |date=July 1966 |pages=38–40, 76–77}}</ref> ''Up Your Ass'' remains unpublished.<ref name=Heller2001/> Harding described her as "an avant-gardist".<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=29}}</ref> |

|||

In 1967, Solanas encountered [[Andy Warhol]] outside his studio, [[The Factory]], and asked him to produce |

In 1967, Solanas encountered [[pop art]]ist [[Andy Warhol]] outside his studio, [[The Factory]], and asked him to produce ''Up Your Ass''. He accepted the manuscript for review, told Solanas it was "well typed", and promised to read it.<ref name="Nickels2005C" /> According to Factory lore, Warhol, whose films were often shut down by the police for obscenity, thought the script was so pornographic that it must have been a police trap.<ref name=Barron>{{cite news|first=James|last=Barron|date=June 23, 2009|url=http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/06/23/a-manuscript-a-confrontation-a-shooting/|title=A Manuscript, a Confrontation, a Shooting|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|access-date=July 6, 2009}}</ref><ref name="KaufmanRosset2004A">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|p=201}}</ref> Solanas contacted Warhol about the script and was told that he had lost it. He also jokingly offered her a job at the Factory as a typist. Insulted, Solanas demanded money for the lost script. Instead, Warhol paid her $25 to appear in his film ''[[I, a Man]]'' (1967).<ref name="Nickels2005C"/> |

||

In her role in ''I, a Man'', |

In her role in ''I, a Man'', Solanas leaves the film's title character, played by [[Tom Baker (American actor)|Tom Baker]], to fend for himself, explaining, "I gotta go beat my meat" as she exits the scene.<ref>{{Cite video | people=Warhol, Andy (Director) |year=1967 | url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0220569 | title=I, a Man | medium=Motion picture }}</ref> She was satisfied with her experience working with Warhol and her performance in the film, and brought [[Maurice Girodias]], the founder of [[Olympia Press]], to see it. Girodias described her as being "very relaxed and friendly with Warhol." Solanas also had a nonspeaking role in Warhol's film ''[[Bike Boy]]'' (1967).<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004A"/> |

||

=== SCUM Manifesto === |

=== ''SCUM Manifesto'' === |

||

{{Main|SCUM Manifesto}} |

{{Main|SCUM Manifesto}} |

||

In 1967, Solanas self-published her best-known work, the ''[[SCUM Manifesto]]'', a scathing critique of patriarchal culture. The manifesto's opening words are: |

|||

In 1967, Solanas self-published her best-known work, the ''SCUM Manifesto'', a scathing critique of [[patriarchy|patriarchal culture]]. The manifesto's opening words are: |

|||

{{Quote|text=<!-- The quotation marks within the quotation are in the original. -->"Life" in this "society" being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of "society" being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex.|sign=Valerie Solanas|source=''SCUM Manifesto''<ref>{{harvp|Solanas|1967|p=1}}</ref>}} |

|||

{{Blockquote|text=<!-- The quotation marks within the quotation are in the original. -->"Life" in this "society" being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of "society" being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex.<ref name="harvp|Solanas|1967|p=1">{{harvp|Solanas|1967|p=1}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|DeMonte|2010|p=178}}</ref>}} |

|||

Some authors have argued that the ''Manifesto'' is [[SCUM Manifesto#As parody and satire|a parody of patriarchy and a satirical work]] and, according to Harding, Solanas described herself as "a social propagandist",<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=152}}, citing {{harvp|Frank|1996|p=211}}</ref> but Solanas denied that the work was "a put on"<ref name="Marmorstein_9">{{harvp|Marmorstein|1968|p=9}}</ref> and insisted that her intent was "dead serious."<ref name="Marmorstein_9"/> The ''Manifesto'' has been translated into over a dozen languages and is excerpted in several feminist anthologies.<ref>{{harvp|Hewitt|2004|p=603}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Morgan|1970|pp=514–519}}</ref><ref>See also {{harvp|Rich|1993|p=17}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=165}}, citing as excerpting ''SCUM Manifesto'' Kolmar, Wendy, & Frances Bartkowski, eds., ''Feminist Theory: A Reader'' (Mountain View, Calif.: Mayfield, 2000), & Albert, Judith Clavir, & Stewart Edward Albert, eds., ''The Sixties Papers: Documents of a Rebellious Decade'' (1984).</ref> |

|||

Some authors have argued that the ''Manifesto'' is a [[SCUM Manifesto#As parody and satire|parody and satirical work]] targeting patriarchy. According to Harding, Solanas described herself as "a social propagandist,"<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=152}}, citing {{harvp|Frank|1996|p=211}}</ref> but she denied that the work was "a put on"<ref name="Marmorstein_9">{{harvp|Marmorstein|1968|p=9}}</ref> and insisted that her intent was "dead serious."<ref name="Marmorstein_9"/> According to another source, Solanas later wrote that The Manifesto was satirical<ref>{{Cite web |date=May 7, 2015 |title=June 14, 2004 {{!}} The Nation |url=http://www.thenation.com/issue/june-14-2004 |access-date=February 11, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150507025243/http://www.thenation.com/issue/june-14-2004 |archive-date=May 7, 2015 }}</ref> and "was designed to provoke debate rather than a practical plan of action".<ref>{{Cite web |date=June 13, 2010 |title=ipl2 Literary Criticism |url=http://ipl.org/div/litcrit/bin/litcrit.out.pl?ti=scu-1177 |access-date=February 11, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100613085746/http://ipl.org/div/litcrit/bin/litcrit.out.pl?ti=scu-1177 |archive-date=June 13, 2010 }}</ref> The ''Manifesto'' has been translated into over a dozen languages and is excerpted in several [[feminism|feminist]] anthologies.<ref>{{harvp|Hewitt|2004|p=603}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Morgan|1970|pp=514–519}}</ref><ref>See also {{harvp|Rich|1993|p=17}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=165}}, citing as excerpting ''SCUM Manifesto'' Kolmar, Wendy, & Frances Bartkowski, eds., ''Feminist Theory: A Reader'' (Mountain View, Calif.: Mayfield, 2000), & Albert, Judith Clavir, & Stewart Edward Albert, eds., ''The Sixties Papers: Documents of a Rebellious Decade'' (1984).</ref> |

|||

While living at the [[Hotel Chelsea|Chelsea Hotel]], Solanas introduced herself to [[Maurice Girodias]], the founder of [[Olympia Press]] and a fellow resident of the hotel. In August 1967, Girodias and Solanas signed<ref>{{harvp|Harron|1996|p=xxi}}</ref> an informal contract stating that she would give Girodias her "next writing, and other writings."<ref name="Baer-Outlaw-p202">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|p=202}}</ref> In exchange, Girodias paid her $500.<ref name="Baer-Outlaw-p202" /><ref name=Watson334>{{harvp|Watson|2003|p=334}}</ref><ref name="BaerAbt-p51">{{harvp|Baer|1996|p=51}}</ref> She took this to mean that Girodias would own her work.<ref name="BaerAbt-p51" /> She told [[Paul Morrissey]] that "everything I write will be his. He's done this to me ...<!-- 3-dot space-surrounded ellipsis, not 4-dot, because replacing comma, not period, despite next letter being capitalized, per sourcing (two sources agree) --> He's screwed me!"<ref name="BaerAbt-p51"/> Solanas intended to write a novel based around the ''SCUM Manifesto'', and believed that a conspiracy was behind Warhol's failure to return the ''Up Your Ass'' script. She suspected that he was coordinating with Girodias to steal her work. |

|||

While living at the [[Hotel Chelsea|Chelsea Hotel]], Solanas introduced herself to Girodias, a fellow resident of the hotel. In August 1967, Girodias and Solanas signed<ref>{{harvp|Harron|1996|p=xxi}}</ref> an informal contract stating that she would give Girodias her "next writing, and other writings."<ref name="Baer-Outlaw-p202">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|p=202}}</ref> In exchange, Girodias paid her $500.<ref name="Baer-Outlaw-p202" /><ref name=Watson334>{{harvp|Watson|2003|p=334}}</ref><ref name="BaerAbt-p51">{{harvp|Baer|1996|p=51}}</ref> Solanas took this to mean that Girodias would own her work.<ref name="BaerAbt-p51" /> She told [[Paul Morrissey]] that "everything I write will be his. He's done this to me ... He's screwed me!"<ref name="BaerAbt-p51"/> Solanas intended to write a novel based on the ''SCUM Manifesto'' and believed that a conspiracy was behind Warhol's failure to return the ''Up Your Ass'' script. She suspected that he was coordinating with Girodias to steal her work. |

|||

=== Shooting === |

|||

In early 1968, Solanas went to writer [[Paul Krassner]] to ask him for $50. In a 2009 written account, Krassner rejected part of Morrissey's account and maintained that Solanas asked him for the money for food and he loaned it to her.<ref name="BrainDamageCtrl-HiTimes">[http://hightimes.com/lounge/pkrassner/5855 Krassner, Paul, ''Brain Damage Control: Phil Spector, Valerie Solanas and Me'', in ''High Times'' ([§] ''Lounge''), September 10, 2009, 5:27 p.m.]. Retrieved August 18, 2012 (uncertain if only online or also printed in ''High Times'', October, 2009).</ref> Krassner later speculated that Solanas could have used the money to buy the gun as the shooting was a few days later.<ref name="BrainDamageCtrl-HiTimes" /> According to Freddie Baer, when Solanas asked Krassner for money in 1968, she told him she wanted to shoot Maurice Girodias and she used the $50 Krassner gave her to buy a [[.32 ACP|.32 automatic pistol]].<ref>{{harvp|Baer|1996|pp=51–52}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|pp=198–205}}</ref> In any event, Krassner denied that he knew that Solanas intended to kill Warhol when she asked to borrow money from him.<ref name="BrainDamageCtrl-HiTimes" /> |

|||

=== Shooting === |

|||

According to an unquoted source in ''The Outlaw Bible of American Literature'', on June 3, 1968, at 9:00 am, Solanas arrived at the [[Hotel Chelsea|Chelsea Hotel]], where Girodias lived. She asked for him at the desk but was told he was gone for the weekend. She remained for three hours before heading to the [[Grove Press]], where she asked for [[Barney Rosset]], who was also not available.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|pp=202–203}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Andy Warhol by Jack Mitchell.jpg|thumb|[[Andy Warhol]]]] |

|||

According to an unquoted source in ''The Outlaw Bible of American Literature'', on June 3, 1968, at 9:00 a.m., Solanas reportedly arrived at the Hotel Chelsea and asked for Girodias at the desk, only to be told he was gone for the weekend. She remained at the hotel for three hours before heading to the [[Grove Press]], where she asked for [[Barney Rosset]], who was also not available.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|pp=202–203}}</ref> In her 2014 biography of Solanas, Breanne Fahs argues that it is unlikely that she appeared at the Chelsea Hotel looking for Girodias, speculating that Girodias may have fabricated the account in order to boost sales for the ''SCUM Manifesto'', which he had published.<ref name="Fahs_133">{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=133}}</ref> |

|||

Fahs states that "the more likely story ... places Valerie at the [[Actors Studio]] at 432 West Forty-Fourth Street early that morning."<ref name=Fahs_133-134/> Actress [[Sylvia Miles]] states that Solanas appeared at the Actors Studio looking for [[Lee Strasberg]], asking to leave a copy of ''Up Your Ass'' for him.<ref name=Fahs_133-134>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|pp=133–134}}</ref> Miles said that Solanas "had a different look, a bit tousled, like somebody whose appearance is the last thing on her mind."<ref name="Fahs_133"/> Miles told Solanas that Strasberg would not be in until the afternoon, accepted the script, and then "shut the door because I knew she was trouble. I didn't know what sort of trouble, but I knew she was trouble."<ref name="Fahs_133"/> |

|||

Fahs records that Solanas then traveled to producer Margo Feiden's (then Margo Eden) residence in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, as |

Fahs records that Solanas then traveled to producer [[Margo Feiden]]'s (then Margo Eden) residence in [[Crown Heights, Brooklyn]], as she believed that Feiden would be willing to produce ''Up Your Ass''. As related to Fahs, Solanas talked to Feiden for almost four hours, trying to convince her to produce the play and discussing her vision for a world without men. Throughout this time, Feiden repeatedly refused to produce the play. According to Feiden, Solanas then pulled out her gun, and when Feiden again refused to commit to producing the play, she responded, "Yes, you will produce the play because I'll shoot Andy Warhol and that will make me famous and the play famous, and then you'll produce it." As she was leaving Feiden's residence, Solanas handed Feiden a partial copy of an earlier draft of the play and other personal papers.<ref name="Fahs_F198">{{harvp|Fahs|2014}}, |

||

[https://books.google.com/books?id=h9ZWAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT323 footnote 198]</ref><ref>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|pp=134–137}}</ref> |

|||

Fahs describes how Feiden then "frantically called her local police precinct, Andy Warhol's precinct, police headquarters in Lower Manhattan, and the offices of Mayor [[John Lindsay]] and Governor [[Nelson Rockefeller]] to report what happened and inform them that Solanas was on her way at that very moment to shoot Andy Warhol."<ref name="Fahs_137">{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=137}}</ref> In some instances, the police responded that "You can't arrest someone because you believe she is going to kill Andy Warhol," and even asked Feiden "Listen lady, how would you know what a real gun looked like?"<ref name="Fahs_137"/> In a 2009 interview with James Barron of ''The New York Times'', Feiden said that she |

Fahs describes how Feiden then "frantically called her local police precinct, Andy Warhol's precinct, police headquarters in [[Lower Manhattan]], and the offices of [[Mayor of New York City|Mayor]] [[John Lindsay]] and [[Governor of New York|Governor]] [[Nelson Rockefeller]] to report what happened and inform them that Solanas was on her way at that very moment to shoot Andy Warhol."<ref name="Fahs_137">{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=137}}</ref> In some instances, the police responded that "You can't arrest someone because you believe she is going to kill Andy Warhol," and even asked Feiden, "Listen lady, how would you know what a real gun looked like?"<ref name="Fahs_137"/> In a 2009 interview with James Barron of ''[[The New York Times]]'', Feiden said that she knew Solanas intended to kill Warhol, but could not prevent it.<ref name="Barron"/>{{Efn|"The ''Times'' does not present Ms. Fieden's account as definitive.... [but] consider[s] this just one angle of the story".<ref name="not_definitive">[http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/06/23/a-manuscript-a-confrontation-a-shooting/#comment-467927 Collins, Nicole (assistant metropolitan editor), comment 3, June 23, 2009, 10:03 a.m.], as accessed June 13, 2013.</ref>}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://podcast.cbc.ca/mp3/qpodcast_20090706.mp3 |title=Ghomeshi, Jian, host, ''Q: The Podcast'', from ''CBC Radio 1'' |access-date=July 7, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121105050737/http://podcast.cbc.ca/mp3/qpodcast_20090706.mp3 |archive-date=November 5, 2012 }}, as accessed November 18, 2012 (interview of Margo Feiden overall approx. 1:14–18:56 from start) (fragment approx. 5:06–5:45 from start) (based on cbc.ca link before archive.org link provided here).</ref><ref name="Interview">{{Cite journal|last=O'Brien|first=Glenn|title=History Rewrite|journal=Interview Magazine|date=March 24, 2009|pages=1–3|url=http://www.interviewmagazine.com/culture/history-rewrite/|access-date=October 18, 2012}}</ref> (A ''New York Times'' assistant Metro editor responded to an online comment regarding the story, saying that the ''Times'' "does not present the account as definitive.")<ref name="not_definitive"/> |

||

Solanas proceeded to the Factory and waited outside. Morrissey arrived and asked her what she was doing there, and she replied, "I'm waiting for Andy to get money."<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p203">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|p=203}}</ref> Morrissey tried to get rid of her by telling her that Warhol was not coming in that day, but she told him she would wait. At 2:00 p.m. Solanas went up into the studio. Morrissey told her again that Warhol was not coming in and that she had to leave. She left but rode the elevator up and down until Warhol finally boarded it.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C" /> |

|||

Fahs additionally cites Assistant District Attorney Roderick Lankler's handwritten notes on the case, written on June 4, 1968, which begin with Margo Feiden's stage name, "Margo Eden", address, and telephone numbers at the top of the page.<ref>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=347}}</ref> |

|||

Solanas entered [[The Factory]] with Warhol, who complimented her on her appearance as she was uncharacteristically wearing makeup. Morrissey told her to leave, threatening to "beat the hell" out of her and throw her out otherwise.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p203" /> The phone rang and Warhol answered while Morrissey went to the bathroom. While Warhol was on the phone, Solanas fired at him three times. Her first two shots missed, but the third went through his [[spleen]], [[stomach]], [[liver]], [[esophagus]], and [[lung|lungs]].<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C"/> She then shot art critic [[Mario Amaya]] in the [[hip]]. Solanas further tried to shoot [[Frederick W. Hughes|Fred Hughes]], Warhol's manager, but her gun jammed.<ref name="Harding2010C">{{harvp|Harding|2010|pp=151–173}}</ref> Hughes asked her to leave, which she did, leaving behind a paper bag with her address book on a table.<ref name="Harding2010C"/> Warhol was taken to [[Cabrini Medical Center|Columbus–Mother Cabrini Hospital]], where he underwent a successful five-hour operation.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C"/><ref>{{harvp|Dillenberger|2001|p=31}}</ref> |

|||

Later that day, Solanas arrived at the Factory and waited outside. Morrissey arrived and asked her what she was doing there, and she replied "I'm waiting for Andy to get money".<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p203">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|p=203}}</ref> Morrissey tried to get rid of her by telling her that Warhol was not coming in that day, but she told him she would wait. At 2:00 pm she went up into the studio. Morrissey told her again that Warhol was not coming in and that she had to leave. She left but rode the elevator up and down until Warhol finally boarded it.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C" /> |

|||

Later that day, Solanas turned herself in to police, gave up her gun, and confessed to the shooting,<ref>{{harvp|Baer|1996|p=53}}</ref> telling an officer that Warhol "had too much control in my life."<ref name="Harding2010B">{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=152}}</ref> She was fingerprinted and charged with [[felonious assault]] and possession of a deadly weapon.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p204">{{harvp|Kaufman|Ortenberg|Rosset|2004|p=204}}</ref> The next morning, the New York ''[[New York Daily News|Daily News]]'' ran the front-page headline: "Actress Shoots Andy Warhol." Solanas demanded a retraction of the statement that she was an actress. The ''Daily News'' changed the headline in its later edition and added a quote from Solanas stating, "I'm a writer, not an actress."<ref name="Harding2010B"/> |

|||

She entered [[The Factory]] with Warhol, who complimented her on her appearance as she was uncharacteristically wearing makeup. Morrissey told her to leave, threatening to "beat the hell"<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p203" /> out of her and throw her out otherwise. The phone rang and Warhol answered while Morrissey went to the bathroom. While Warhol was on the phone, Solanas fired at him three times. She missed twice, but the third shot went through both lungs, his spleen, stomach, liver, and esophagus.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C"/> She then shot art critic [[Mario Amaya]] in the hip. She tried to shoot Fred Hughes, Warhol's manager, in the head but her gun jammed.<ref name="Harding2010C">{{harvp|Harding|2010|pp=151–173}}</ref> Hughes asked her to leave, which she did, leaving behind a paper bag with her address book on a table.<ref name="Harding2010C"/> Warhol was taken to [[Cabrini Medical Center|Columbus–Mother Cabrini Hospital]], where he underwent a five-hour, successful operation.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C"/><ref>{{harvp|Dillenberger|2001|p=31}}</ref> |

|||

At her arraignment in [[Manhattan Criminal Court]], Solanas denied shooting Warhol because he wouldn't produce her play but said "it was for the opposite reason",<ref name="ActressDefiant-col1">{{cite news |last1=Faso |first1=Frank |first2=Henry |last2=Lee |date=June 5, 1968 |title=Actress defiant: 'I'm not sorry' |newspaper=[[New York Daily News]] |volume=49 |issue=297 |page=42}}</ref> that "he has a legal claim on my works."<ref name="ActressDefiant-col1" /> She told the judge that "it's not often that I shoot somebody. I didn't do it for nothing. Warhol had tied me up, lock, stock, and barrel. He was going to do something to me which would have ruined me."<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p204"/> She declared that she wanted to represent herself<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p204" /> and she insisted that she "was right in what I did! I have nothing to regret!"<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p204" /> The judge struck Solanas' comments from the court record<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p204" /> and had her admitted to [[Bellevue Hospital]] for psychiatric observation.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p204"/> |

|||

=== Trial === |

=== Trial === |

||

{{Quote box |width= |

{{Quote box |width=26em |align=right |bgcolor=#c6dbf7 |halign=left |quote= I consider that a moral act. And I consider it immoral that I missed. I should have done target practice.|source = — Valerie Solanas on her assassination attempt on Andy Warhol<ref name="replies">{{cite journal |title=Valerie Solanas replies |date=August 1, 1977 |journal=The Village Voice |volume=XXII |issue=31 |page=29}}</ref><ref name=Third>{{harvp|Third|2006}}</ref>}} |

||

After a cursory evaluation, Solanas was declared mentally unstable and transferred to the prison ward of Elmhurst Hospital.<ref>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=198}}</ref> |

After a cursory evaluation, Solanas was declared mentally unstable and transferred to the prison ward of [[Elmhurst Hospital Center|Elmhurst Hospital]].<ref>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=198}}</ref> She appeared at [[New York Supreme Court]] on June 13, 1968. [[Florynce Kennedy]] represented her and asked for a writ of ''[[habeas corpus]]'', arguing that Solanas was being held inappropriately at Elmhurst. The judge denied the motion and Solanas returned to Elmhurst. On June 28, Solanas was indicted on charges of [[attempted murder]], assault, and illegal possession of a firearm. She was declared "incompetent" in August and sent to [[Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane]].<ref>{{harvp|Fahs|2014|p=221}}</ref> That same month, Olympia Press published the ''SCUM Manifesto'' with essays by Girodias and Krassner.<ref name="KaufmanRosset2004C-p204"/> |

||

In January |

In January 1969, Solanas underwent psychiatric evaluation and was diagnosed with chronic [[paranoid schizophrenia]].<ref name=Watson35/> In June, she was deemed fit to stand trial. She represented herself without an attorney and pleaded guilty to "reckless assault with intent to harm."<ref name=Jansen153>{{harvp|Jansen|2011|p=153}}</ref><ref name=AKPress55>{{harvp|Solanas|1996|p=55}}</ref> Solanas was sentenced to three years in prison, with one year of time served.<ref name=Jansen153/><ref name=AKPress55/> |

||

== After murder attempt == |

== After murder attempt == |

||

The shooting of Warhol propelled Solanas into the public spotlight, prompting a flurry of commentary and opinions in the media. Robert Marmorstein, writing in ''[[The Village Voice]]'', declared that Solanas "has dedicated the remainder of her life to the avowed purpose of eliminating every single male from the face of the earth."<ref name="Marmorstein_9"/> [[Norman Mailer]] called her the "[[Maximilien Robespierre|Robespierre]] of feminism."<ref name="Nickels2005D"/> |

The shooting of Warhol propelled Solanas into the public spotlight, prompting a flurry of commentary and opinions in the media. Robert Marmorstein, writing in ''[[The Village Voice]]'', declared that Solanas "has dedicated the remainder of her life to the avowed purpose of eliminating every single male from the face of the earth."<ref name="Marmorstein_9"/> [[Norman Mailer]] called her the "[[Maximilien Robespierre|Robespierre]] of feminism."<ref name="Nickels2005D"/> |

||

[[Ti-Grace Atkinson]], the New York chapter president of the [[National Organization for Women]] (NOW), described Solanas as "the first outstanding champion of women's rights"<ref name="Nickels2005D">{{harvp|Nickels|2005|p=17}}</ref> and |

[[Ti-Grace Atkinson]], the New York chapter president of the [[National Organization for Women]] (NOW), described Solanas as "the first outstanding champion of women's rights"<ref name="Nickels2005D">{{harvp|Nickels|2005|p=17}}</ref> and "a 'heroine' of the feminist movement,"<ref name="Friedan_109">{{harvp|Friedan|1976|p=109}}</ref><ref name="Friedan_138">{{harvp|Friedan|1998|p=138}}</ref> and "smuggled [her manifesto] ... out of the mental hospital where Solanas was confined."<ref name="Friedan_109"/><ref name="Friedan_138"/> According to [[Betty Friedan]], the NOW board rejected Atkinson's statement.<ref name="Friedan_138"/> Atkinson left NOW and founded another feminist organization.<ref>{{harvp|Willis|1992|p=124}}</ref> According to Friedan, "the media continued to treat Ti-Grace as a leader of the women's movement, despite its repudiation of her."<ref>{{harvp|Friedan|1998|p=139}}</ref> Kennedy, another NOW member, called Solanas "one of the most important spokeswomen of the feminist movement."<ref name="Nickels2005C"/><ref name="solanas1996">{{harvp|Solanas|1996|p=54}}</ref> |

||

English professor [[Dana Heller]] argued that Solanas was "very much aware of feminist organizations and activism,"<ref name="Heller_160">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=160}}</ref> but "had no interest in participating in what she often described as 'a [[civil disobedience]] [[luncheon]] club.'"<ref name="Heller_160"/> Heller also stated that Solanas could "reject mainstream [[liberal feminism]] for its blind adherence to cultural codes of feminine politeness and decorum which the ''SCUM Manifesto'' identifies as the source of women's debased social status."<ref name="Heller_160"/> |

|||

Another NOW member, [[Florynce Kennedy]], called her "one of the most important spokeswomen of the feminist movement."<ref name="Nickels2005C"/><ref name="solanas1996">{{harvp|Solanas|1996|p=54}}</ref> Dissatisfied with NOW's approach to change, Kennedy also left in 1970 and founded the Feminist Party in 1971. |

|||

English professor Dana Heller argued that Solanas was "very much aware of feminist organizations and activism",<ref name="Heller_160">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=160}}</ref> but that she "had no interest in participating in what she often described as 'a civil disobedience luncheon club.'"<ref name="Heller_160"/> Heller also stated that Solanas could "reject mainstream liberal feminism for its blind adherence to cultural codes of feminine politeness and decorum which the ''SCUM Manifesto'' identifies as the source of women's debased social status."<ref name="Heller_160"/>{{Efn|[[Liberal feminism]], feminism based on women showing and maintaining their equality by their own choices and acts.}} |

|||

=== Solanas and Warhol === |

=== Solanas and Warhol === |

||

After Solanas was released from the New York State Prison for Women in 1971,<ref name=Buchanan48>{{harvp|Buchanan|2011|p=48}}</ref> she [[stalking|stalked]] Warhol and others over the telephone and was arrested again in November 1971.<ref |

After Solanas was released from the New York State Prison for Women in 1971,<ref name=Buchanan48>{{harvp|Buchanan|2011|p=48}}</ref> she [[stalking|stalked]] Warhol and others over the telephone and [[Recidivism|was arrested again]] in November 1971.<ref name="AKPress55"/> She was subsequently institutionalized several times and then drifted into obscurity.<ref>{{harvp|Solanas|1996|pp=55–56}}</ref> |

||

The |

The shooting had a profound impact on Warhol and his art, and security at the Factory became much stronger afterward. For the rest of his life, Warhol lived in fear that Solanas would attack him again. "It was the Cardboard Andy, not the Andy I could love and play with," said close friend and collaborator [[Billy Name]]. "He was so sensitized you couldn't put your hand on him without him jumping. I couldn't even love him anymore, because it hurt him to touch him."<ref>{{cite news|first=Dennis|last=Drabelle|url=http://www.factorymade.org/fm/reviews.html|title=Making the Scene: Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties by Steven Watson (review)|newspaper=[[The Washington Post]]|date=November 16, 2003|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070403213531/http://www.factorymade.org/fm/reviews.html |archive-date=April 3, 2007}}</ref> |

||

== Later life == |

== Later life == |

||

Solanas may have intended to write an eponymous autobiography.<ref>{{harvp|Winkiel|1999|p=74}}</ref> In a 1977 ''Village Voice'' interview,<ref name="Heller_151">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=151}}</ref> she announced a book with her name as the title.<ref>[[Howard Smith (director)|Smith, Howard]], & Brian Van der Horst, ''Valerie Solanas Interview'', in ''Scenes'' (col.), in ''The Village Voice'' (New York, N.Y.), vol. XXII, no. 30, July 25, 1977, p. 32, col. 2.</ref> The book, possibly intended as a parody, was supposed to deal with the "conspiracy" that led to her imprisonment.<ref name="Heller_151"/> In a corrective 1977 ''Village Voice'' interview, Solanas said the book would not be autobiographical other than a small portion and that it would be about many things, include proof of statements in the manifesto, and would "deal ''very'' intensively with the subject of bullshit," but she said nothing about parody.<ref name="replies"/> |

|||

[[File:Bristol Hotel San Francisco 01.jpg|thumb|right|upright|Solanas died in 1988 of pneumonia at the Bristol Hotel in San Francisco.]] |

|||

Solanas may have intended to write an eponymous autobiography.<ref>{{harvp|Winkiel|1999|p=74}}</ref> In a 1977 ''[[The Village Voice|Village Voice]]'' interview,<ref name="Heller_151">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=151}}</ref> she announced a book with her name as the title.<ref>[[Howard Smith (director)|Smith, Howard]], & Brian Van der Horst, ''Valerie Solanas Interview'', in ''Scenes'' (col.), in ''The Village Voice'' (New York, N.Y.), vol. XXII, no. 30, July 25, 1977, p. 32, col. 2.</ref> The book, possibly intended as a parody, was supposed to deal with the conspiracy which led to her imprisonment.<ref name="Heller_151"/> In a corrective 1977 ''Village Voice'' interview, Solanas said the book would not be autobiographical other than a small portion and that it would be about many things, include proof of statements in the manifesto, and "deal ''very'' intensively with the subject of bullshit", but she said nothing about parody.<ref name="replies"/> |

|||

In the mid-1970s, in New York City, according to Heller, Solanas was "apparently homeless",<ref name="Heller_164">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=164}}</ref> "continued to defend her political beliefs and the ''SCUM Manifesto''",<ref name="Heller_164"/> and "actively promoted" her own new ''Manifesto'' revision.<ref name="Heller_164"/> |

|||

In the mid-1970s, according to Heller, Solanas was "apparently homeless" in New York City,<ref name="Heller_164">{{harvp|Heller|2008|p=164}}</ref> "continued to defend her political beliefs and the ''SCUM Manifesto''",<ref name="Heller_164"/> and "actively promoted" her new ''Manifesto'' revision.<ref name="Heller_164"/> In the late 1980s, [[Isabelle Collin Dufresne|Ultra Violet]] tracked down Solanas in [[northern California]] and interviewed her over the phone.<ref>{{harvp|Violet|1990|p=v}}</ref> According to Ultra Violet, Solanas had changed her name to Onz Loh and stated that the August 1968 version of the ''Manifesto'' had many errors, unlike her own printed version of October 1967, and that the book had not sold well. Solanas said that until she was informed by Violet, she was unaware of Warhol's death in 1987.<ref>{{harvp|Violet|1990|pp=183–189}}</ref>{{Efn|Violet objected to assassination;<ref>{{harvp|Violet|1990|p=189}}</ref> for a possible contrast in her views, see {{harvp|Violet|1990|p=241}} for another near-killing of Warhol.}} |

|||

== Death == |

|||

On April 25, 1988, at the age of 52, Solanas died of [[pneumonia]] at the [[Hotel Bristol|Bristol Hotel]] in the [[Tenderloin, San Francisco|Tenderloin district]] of San Francisco.<ref>{{harvp|Watson|2003|p=425}}</ref> A building superintendent at the hotel, not on duty that night, had a vague memory of Solanas: "Once, he had to enter her room, and he saw her typing at her desk. There was a pile of typewritten pages beside her. What she was writing and what happened to the manuscript remain a mystery."<ref name="Coburn"/><ref>{{harvp|Harron|1996|p=xxxi}}</ref> Her mother burned all her belongings posthumously.<ref name="Coburn"/> |

|||

[[File:Grave of Valerie Jean Solanas - Stierch.JPG|thumb|The grave of Valerie Jean Solanas at Saint Marys Catholic Church Cemetery, Fairfax County, Virginia]] |

[[File:Grave of Valerie Jean Solanas - Stierch.JPG|thumb|The grave of Valerie Jean Solanas at Saint Marys Catholic Church Cemetery, Fairfax County, Virginia]] |

||

On April 25, 1988, at the age of 52, Valerie Solanas died of [[pneumonia]] at the [[Hotel Bristol|Bristol Hotel]] in the [[Tenderloin, San Francisco|Tenderloin district]] of San Francisco.<ref>{{harvp|Watson|2003|p=425}}</ref> A building superintendent at the hotel, not on duty that night, had a vague memory of Solanas: "Once, he had to enter her room, and he saw her typing at her desk. There was a pile of typewritten pages beside her. What she was writing and what happened to the manuscript remain a mystery."<ref name="Coburn"/><ref>{{harvp|Harron|1996|p=xxxi}}</ref> Her mother burned all her belongings posthumously.<ref name="Coburn"/> |

|||

== Legacy == |

== Legacy == |

||

=== Popular culture === |

=== Popular culture === |

||

Composer [[Pauline Oliveros]] released "To Valerie Solanas and [[Marilyn Monroe]] in Recognition of Their Desperation" in 1970. In the work, Oliveros seeks to explore how, "Both women seemed to be desperate and caught in the traps of inequality: Monroe needed to be recognized for her talent as an actress. Solanas wished to be supported for her own creative work."<ref name="Oliveros">{{cite web| first=Pauline| last=Oliveros| title=To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of Their Desperation (1970)| url=http://www.deeplistening.org/site/content/valerie-solanas-and-marilyn-monroe-recognition-their-desperation-1970-0| publisher=Deep Listening| date=September 1970| access-date=November 27, 2011| archive-date=August 13, 2017| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170813231042/http://www.deeplistening.org/site/content/valerie-solanas-and-marilyn-monroe-recognition-their-desperation-1970-0| url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="Marilyn">{{cite web | title=Pauline Oliveros | publisher=Roaratorio | url=http://roaratorio.com/21.html | access-date=November 27, 2011 | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120426005046/http://roaratorio.com/21.html | archive-date=April 26, 2012 | df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

|||

Solanas's life has been the focus of numerous performances, films, musical compositions, and publications. |

|||

In 1996, actress [[Lili Taylor]] played Solanas in the film ''[[I Shot Andy Warhol]]'', which focused on Solanas's assassination attempt on Warhol. Taylor won Special Recognition for Outstanding Performance at the [[Sundance Film Festival]] for her role.<ref name="Taylor1">{{Cite web|author=B. Ruby Rich|year=1996|title=I Shot Andy Warhol|work=Archives|publisher=[[Sundance Institute]]|url=http://history.sundance.org/films/1347 |accessdate=November 27, 2011}}</ref> The film's director, [[Mary Harron]], requested permission to use songs by [[The Velvet Underground]], but was denied by [[Lou Reed]], who feared that Solanas would be glorified in the film. Six years before the film's release, Reed and [[John Cale]] included a song about Solanas, "I Believe," on their [[concept album]] about Warhol, ''[[Songs for Drella]]'' (1990). In "I Believe", Reed sings, "I believe life's serious enough for retribution... I believe being sick is no excuse. And I believe I would've pulled the switch on her myself." Reed believed Solanas was to blame for Warhol's death from a [[gallbladder]] infection 20 years after she shot him.<ref name="Reed1">{{Cite web | author=Michael Schaub | date=November 2003 | title=The 'Idiot Madness' of Valerie Solanis | publisher=[[Bookslut]] | url=http://www.bookslut.com/propaganda/2003_11_000965.php | accessdate= November 27, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Actress [[Lili Taylor]] played Solanas in the film ''[[I Shot Andy Warhol]]'' (1996), which focused on Solanas's assassination attempt on Warhol (played by [[Jared Harris]]). Taylor won Special Recognition for Outstanding Performance at the [[Sundance Film Festival]] for her role.<ref name="Taylor1">{{cite web|author=B. Ruby Rich|year=1996|title=I Shot Andy Warhol|work=Archives|publisher=[[Sundance Institute]]|url=http://history.sundance.org/films/1347 |access-date=November 27, 2011}}</ref> The film's director, [[Mary Harron]], requested permission to use songs by [[The Velvet Underground]] but was denied by [[Lou Reed]], who feared that Solanas would be glorified in the film. Six years before the film's release, Reed and [[John Cale]] included a song about Solanas, "I Believe," on their [[concept album]] about Warhol, ''[[Songs for Drella]]'' (1990). In "I Believe," Reed sings, "I believe life's serious enough for retribution... I believe being sick is no excuse. And I believe I would've pulled the switch on her myself." Reed believed Solanas was to blame for Warhol's death from a [[gallbladder]] infection twenty years after she shot him.<ref name="Reed1">{{cite web | first=Michael | last=Schaub | date=November 2003 | title=The 'Idiot Madness' of Valerie Solanis | work=[[Bookslut]] | url=http://www.bookslut.com/propaganda/2003_11_000965.php | access-date=November 27, 2011 | archive-date=August 19, 2013 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130819164243/http://www.bookslut.com/propaganda/2003_11_000965.php | url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

Three plays have been based around Solanas' life. ''Valerie Shoots Andy'', by Carson Kreitzer, from 2001, which starred two actresses playing a younger (Heather Grayson) and an older (Lynne McCollough) Solanas.<ref name="Genzlinger">{{Cite news|author=Neil Genzlinger|title=Theater Review; A Writer One Day, a Would-Be Killer the Next: Reliving the Warhol Shooting|work=Andy Warhol|publisher=[[The New York Times]]|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2001/03/01/theater/theater-review-writer-one-day-would-be-killer-next-reliving-warhol-shooting.html |accessdate=November 27, 2011|date=March 1, 2001}}</ref> ''Tragedy in Nine Lives'', by Karen Houppert, in 2003, examined the encounter between Solanas and Warhol as a [[Greek tragedy]] and starred [[Juliana Francis]] as Solanas.<ref name="Carr">{{Cite web | author=C. Carr | date=July 22, 2003 | title=SCUM Goddess | publisher=[[Village Voice]] | url=http://www.villagevoice.com/arts/scum-goddess-7141341 | accessdate= August 13, 2015}}</ref> Most recently, in 2011, was ''Pop!'', a musical by Maggie-Kate Coleman and Anna K. Jacobs. ''Pop!'' focused mainly on Andy Warhol, with Rachel Zampelli playing Solanas and singing the song "Big Gun", which was described as the "evening's strongest number" by ''[[The Washington Post]]''.<ref name="Marks">{{Cite news | author=Peter Marks | title=Theater review: 'Pop!' paints bold portrait of Warhol and his inner circle | work=Style |publisher=The Washington Post| url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/theater-review-pop-paints-bold-portrait-of-warhol-and-his-inner-circle/2011/07/19/gIQAjEgaOI_story.html | accessdate= November 27, 2011 | date=July 19, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

''Up Your Ass'' was rediscovered in 1999 and produced in 2000 by [[George Coates|George Coates Performance Works]] in San Francisco. The copy Warhol had lost was found in a trunk of lighting equipment owned by Billy Name. Coates learned about the rediscovered manuscript while at an exhibition at [[The Andy Warhol Museum]] marking the 30th anniversary of the shooting. Coates turned the piece into a musical with an all-female cast. Coates consulted with Solanas' sister, Judith, while writing the piece, and sought to create a "very funny satirist" out of Solanas, not just showing her as Warhol's attempted assassin.<ref name="Coburn" /><ref name="Carr"/> |

|||

Solanas' life has inspired three plays. ''Valerie Shoots Andy'' (2001), by Carson Kreitzer, starred two actors playing a younger (Heather Grayson) and an older (Lynne McCollough) Solanas.<ref name="Genzlinger">{{Cite news|first=Neil|last=Genzlinger|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2001/03/01/theater/theater-review-writer-one-day-would-be-killer-next-reliving-warhol-shooting.html|title=Theater Review; A Writer One Day, a Would-Be Killer the Next: Reliving the Warhol Shooting|work=[[The New York Times]]|location=New York City|date=March 1, 2001|access-date=November 27, 2011}}</ref> ''Tragedy in Nine Lives'' (2003), by Karen Houppert, examined the encounter between Solanas and Warhol as a [[Greek tragedy]] and starred [[Juliana Francis]] as Solanas.<ref name="Carr">{{cite web | first=C.|last=Carr | title=SCUM Goddess | url=http://www.villagevoice.com/arts/scum-goddess-7141341 | work=The Village Voice |date=July 22, 2003 |access-date= August 13, 2015}}</ref> Most recently, in 2011, ''Pop!'', a musical by Maggie-Kate Coleman and Anna K. Jacobs, focused mainly on Warhol (played by Tom Story). Rachel Zampelli played Solanas and sang "Big Gun," described as the "evening's strongest number" by ''[[The Washington Post]]''.<ref name="Marks">{{Cite news | first=Peter|last=Marks | url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/theater-review-pop-paints-bold-portrait-of-warhol-and-his-inner-circle/2011/07/19/gIQAjEgaOI_story.html|title=Theater review: 'Pop!' paints bold portrait of Warhol and his inner circle | newspaper=[[The Washington Post]]|publisher=Nash Holdings LLC|location=Washington DC |date=July 19, 2011|access-date= November 27, 2011 }}</ref> |

|||

Swedish author [[Sara Stridsberg]] wrote a [[semi-fiction]]al novel about Valerie Solanas, called ''Drömfakulteten'' (English: ''The Dream Faculty''). In the book, the narrator visits Solanas towards the end of her life at the Bristol Hotel. Stridsberg was awarded the [[Nordic Council's Literature Prize]] for the book.<ref name="Stridsberg">{{Cite web|year=2007|title=Sara Stridsberg wins the Literature Prize|work=News|publisher=Norden|url=http://www.norden.org/en/news-and-events/news/sara-stridsberg-wins-the-literature-prize |accessdate=November 27, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Swedish author [[Sara Stridsberg]] wrote a [[semi-fiction]]al novel about Solanas called ''Drömfakulteten'' (English: ''The Dream Faculty''), published in 2006. The book's narrator visits Solanas toward the end of her life at the Bristol Hotel. Stridsberg was awarded the [[Nordic Council's Literature Prize]] for the book.<ref name="Stridsberg">{{cite web|year=2007|title=Sara Stridsberg wins the Literature Prize|work=News|publisher=Norden|url=http://www.norden.org/en/news-and-events/news/sara-stridsberg-wins-the-literature-prize|access-date=November 27, 2011|archive-date=May 7, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140507090527/http://www.norden.org/en/news-and-events/news/sara-stridsberg-wins-the-literature-prize|url-status=dead}}</ref> The novel was later translated into and published in English under the title ''Valerie, or, The Faculty of Dreams: A Novel'' in 2019.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374151911 |title=Valerie | Sara Stridsberg | Macmillan |publisher=Us.macmillan.com |date=2019 |access-date=August 7, 2019}}</ref> |

|||

Composer [[Pauline Oliveros]] released a piece titled "To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of Their Desperation" in 1970. Through the work, Oliveros sought to explore how "Both women seemed to be desperate and caught in the traps of inequality: Monroe needed to be recognized for her talent as an actress. Solanas wished to be supported for her own creative work."<ref name="Oliveros">{{Cite web | author=Pauline Oliveros | title=To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of Their Desperation (1970) | publisher=Deep Listening | url=http://www.deeplistening.org/site/content/valerie-solanas-and-marilyn-monroe-recognition-their-desperation-1970-0 | accessdate= November 27, 2011}}</ref><ref name="Marilyn">{{Cite web | title=Pauline Oliveros | publisher=Roaratorio | url=http://roaratorio.com/21.html | accessdate= November 27, 2011}}</ref> There is a music group from Belgium called The Valerie Solanas<!-- Capitalization of "The" so in official name. -->.<ref>{{cite web | title = The Valerie Solanas | publisher = The Valerie Solanas | url = http://www.solanas.be/ | accessdate = January 2014}}</ref> |

|||

In 2006 Solanas was featured in eleventh episode of the second season [[Adult Swim]] show [[The Venture Bros.|The Venture Bros]] as part of a group called The Groovy Gang. The group was a parody of the [[Scooby-Doo|Scooby Gang]] from [[Scooby-Doo]] and was made up of parodies of Solanas ([[Velma Dinkley|Velma]]), [[Ted Bundy]] ([[Fred Jones (Scooby-Doo)|Fred]]), [[David Berkowitz]] ([[Shaggy Rogers|Shaggy]]), [[Patty Hearst]] ([[Daphne Blake|Daphne]]), and [[David Berkowitz|Groovy]] ([[Scooby-Doo (character)|Scooby]]). In the episode she is voiced by [[Joanna P. Adler|Joanna Adler]]. Most of her lines in the episode are quotes from the SCUM Manifesto. |

|||

Welsh rock group the [[Manic Street Preachers]] included an excerpt from the ''SCUM Manifesto'' in the liner notes of their 1992 debut album ''[[Generation Terrorists]]'', in relation to the song "[[Little Baby Nothing]]". That excerpt includes the description of males as "walking abortions;" the Manic Street Preachers released a song titled "Of Walking Abortion" on their 1994 album ''[[The Holy Bible (album)|The Holy Bible]]''. |

|||

Solanas was featured in a 2017 episode of the [[FX (TV channel)|FX]] series ''[[American Horror Story: Cult]]'', "[[Valerie Solanas Died for Your Sins: Scumbag]]." She was played by [[Lena Dunham]].<ref>{{cite web|first=Laura|last=Bradley|url=https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/08/american-horror-story-cult-spoilers|title=How ''American Horror Story: Cult'' Will Change the ''A.H.S.'' Game|work=[[Vanity Fair (magazine)|Vanity Fair]]|publisher=[[Condé Nast]]|location=New York City|date=August 29, 2017|access-date=September 6, 2017}}</ref> The episode portrayed Solanas as the instigator of most of the [[Zodiac Killer]] murders. |

|||

Electronic duo [[Matmos]] wrote ''Tract for Valerie Solanas'', included on their 2006 album ''[[The Rose Has Teeth in the Mouth of a Beast]]''. The track features excerpts from SCUM read by Barbara Golden and Yalie Kumara, and recorded samples of a variety of unusual objects including cow uterus, reproductive tract, vagina, vacuum cleaner, plastic gloves, machete, scissors, knives, paper, and personal alarms (rape alarms). |

|||

=== Influence and analysis === |

=== Influence and analysis === |

||

Author James Martin Harding explained that, by declaring herself independent from Warhol, after her arrest she "aligned herself with the historical [[avant-garde]]'s rejection of the traditional structures of bourgeois theater,"<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=153}}</ref> and that her anti-patriarchal "militant hostility... pushed the avant-garde in radically new directions."<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|pp=29, 30, 31, 33, 153}}</ref> Harding believed that Solanas' assassination attempt on Warhol was its own theatrical performance.<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|loc=chap. 6 esp. pp. 151–158 and see pp. 21, 24, 26, 29, 63 & 178}}</ref> At the shooting, she left on a table at the Factory a paper bag containing a gun, her address book, and a [[sanitary napkin]].<ref name="CuttingPerfs-p151">{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=151}}</ref> Harding stated that leaving behind the sanitary napkin was part of the performance,<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|pp=151–153}}</ref> and called "attention to basic feminine experiences that were {{sic|publi|cally}} taboo and tacitly elided within avant-garde circles."<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|pp=152, 153}}</ref> |

|||

Feminist philosopher [[Avital Ronell]] compared Solanas to an array of people: [[John and Lorena Bobbitt|Lorena Bobbitt]] |

Feminist philosopher [[Avital Ronell]] compared Solanas to an array of people: [[John and Lorena Bobbitt|Lorena Bobbitt]]; a "girl [[Friedrich Nietzsche|Nietzsche]]"; [[Medusa]]; the [[Unabomber]]; and [[Medea]].<ref name=Verso2004>{{harvp|Ronell|2004}}</ref> Ronell believed that Solanas was threatened by the hyper-feminine women of the Factory that Warhol liked and felt lonely because of the rejection she felt due to her own [[butch and femme|butch]] [[androgyny]]. She believed Solanas was ahead of her time, living in a period before feminist and lesbian activists such as the [[Guerrilla Girls]] and the [[Lesbian Avengers]].<ref name="Nickels2005D"/> |

||

Solanas has also been credited with instigating [[radical feminism]].<ref name=Third/> Catherine Lord wrote that "the feminist movement would not have happened without Valerie Solanas."<ref name=Lord/> Lord believed that the reissuing of the ''SCUM Manifesto'' and the disowning of Solanas by "women's liberation politicos" triggered a wave of radical feminist publications. According to [[Vivian Gornick]], many of the [[women's liberation]] activists who initially distanced themselves from Solanas changed their minds a year later, developing the first wave of radical feminism.<ref name=Lord/> At the same time, perceptions of Warhol were transformed from largely nonpolitical into political martyrdom because the motive for the shooting was political, according to Harding and [[Victor Bockris]].<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=172}}, citing Bockris, Victor, ''The Life and Death of Andy Warhol'', ''op. cit.'', p. 236.</ref> |

Solanas has also been credited with instigating [[radical feminism]].<ref name=Third/> [[Catherine Lord]] wrote that "the feminist movement would not have happened without Valerie Solanas."<ref name=Lord/> Lord believed that the reissuing of the ''SCUM Manifesto'' and the disowning of Solanas by "women's liberation politicos" triggered a wave of radical feminist publications. According to [[Vivian Gornick]], many of the [[women's liberation]] activists who initially distanced themselves from Solanas changed their minds a year later, developing the first wave of radical feminism.<ref name=Lord/> At the same time, perceptions of Warhol were transformed from largely nonpolitical into political martyrdom because the motive for the shooting was political, according to Harding and [[Victor Bockris]].<ref>{{harvp|Harding|2010|p=172}}, citing Bockris, Victor, ''The Life and Death of Andy Warhol'', ''op. cit.'', p. 236.</ref> Solanas' idiosyncratic views on gender are a focus of [[Andrea Long Chu|Andrea Long Chu's]] 2019 book, [[Females (Chu book)|''Females'']].<ref>{{cite web|last1=Lorusso|first1=Melissa|title=In 'Females,' The State Is Less A Biological Condition Than An Existential One|url=https://www.npr.org/2019/10/30/774365692/in-females-the-state-is-less-a-biological-condition-than-an-existential-one|website=NPR|access-date=27 June 2020|date=30 October 2019}}</ref> |

||

Fahs describes Solanas as a contradiction that "alienates her from the feminist movement", arguing that Solanas never wanted to be "in movement" but nevertheless fractured the feminist movement by provoking NOW members to disagree about her case. Many contradictions are seen in Solanas' lifestyle as a lesbian who sexually serviced men, her claim to be [[asexuality|asexual]], a rejection of [[queer culture]], and a non-interest in working with others despite a dependency on others.<ref name=Fahs2008/> Fahs also brings into question the contradictory stories of Solanas' life. She is described as a victim, a rebel, and a desperate loner, yet her cousin says she worked as a [[waitress]] in her late 20s and 30s, not primarily as a prostitute, and friend Geoffrey LaGear said she had a "groovy childhood." Solanas also kept in touch with her father throughout her life, despite claiming that he sexually abused her. Fahs believes that Solanas embraced these contradictions as a key part of her identity.<ref name=Fahs2008/> |

|||

In 2018, ''[[The New York Times]]'' started a series of delayed [[obituary|obituaries]] of significant individuals whose importance the paper's obituary writers had not recognized at the time of their deaths. In June 2020, they started a series of obituaries on LGBTQ individuals, and on June 26, they profiled Solanas.<ref name=nytimes2020-06-26/> |

|||

Alice Echols stated that Solanas' "unabashed [[misandry]]" was not typical within most radical feminist groups during the latter's time.<ref>{{harvp|Echols|1989|p=104–105}}</ref><ref>{{harvp|Echols|1989|p=104}}</ref> |

|||

== Works == |

== Works == |

||

* ''Up Your Ass'' (1965){{Efn|Although ''Up Your Ass'' was written in 1965, it |

* ''Up Your Ass'' (1965){{Efn|Although ''Up Your Ass'' was written in 1965, it was not produced as a play until 2000, and was not published until 2014 (as a [[Amazon Kindle|Kindle]] ebook).<ref>{{cite book |last=Solanas |first= Valerie |date= March 31, 2014 |title=Up Your Ass |publisher=VandA.ePublishing |asin=B00JE6N2UG }}</ref>}} |

||

* "A Young Girl's Primer on How to Attain the Leisure Class |

* "A Young Girl's Primer on How to Attain the Leisure Class," ''[[Cavalier (magazine)|Cavalier]]'' (1966) |

||

* ''[[SCUM Manifesto]]'' (1967) |

* ''[[SCUM Manifesto]]'' (1967) |

||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

{{Notelist |

{{Notelist}} |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

{{reflist| |

{{reflist|refs= |

||

<ref name=nytimes2020-06-26> |

|||

{{cite news |

|||

| url = https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/26/obituaries/valerie-solanas-overlooked.html |

|||

| title = Overlooked No More: Valerie Solanas, Radical Feminist Who Shot Andy Warhol |

|||

| work = [[The New York Times]] |

|||

| date = June 26, 2020 |

|||

| author = Bonnie Wertheim |

|||

| quote = Overlooked is a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times. This month we’re adding the stories of important L.G.B.T.Q. figures. |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

=== Bibliography === |

=== Bibliography === |

||

{{refbegin|32em}} |

{{refbegin|32em}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Baer |first=Freddie |year=1996 |chapter=About Valerie Solanas |pages=48–57 |editor=Valerie Solanas |title=SCUM Manifesto |location=Edinburgh |

* {{cite book |last=Baer |first=Freddie |year=1996 |chapter=About Valerie Solanas |pages=48–57 |editor=Valerie Solanas |title=SCUM Manifesto |location=Edinburgh |publisher=AK Press |isbn=978-1-873176-44-3 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Buchanan |first=Paul D. |year=2011 |title=Radical Feminists: A Guide to an American Subculture |publisher=Greenwood |location=Santa Barbara, CA |isbn=978-1-59884-356-9 |

* {{cite book |last=Buchanan |first=Paul D. |year=2011 |title=Radical Feminists: A Guide to an American Subculture |publisher=Greenwood |location=Santa Barbara, CA |isbn=978-1-59884-356-9 }} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Chu |first1=Andrea Long |title=On Liking Women |journal=N Plus One |date=Winter 2018 |issue=30 |url=https://nplusonemag.com/issue-30/essays/on-liking-women/ |access-date=August 10, 2019 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=DeMonte |first=Alexandra |year=2010 |chapter=Feminism: second-wave |editor=Roger Chapman |title=Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices |location=Armonk, NY |publisher=M. E. Sharpe |isbn=978-1-84972-713-6 |ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=DeMonte |first=Alexandra |year=2010 |chapter=Feminism: second-wave |editor=Roger Chapman |title=Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices |location=Armonk, NY |publisher=M. E. Sharpe |isbn=978-1-84972-713-6 }} |

||

* {{cite |

* {{cite book |last=Dillenberger |first=Jane Daggett |year=2001 |title=The Religious Art of Andy Warhol |publisher=Continuum |location=New York|isbn=978-0826413345 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=Echols |first=Alice |year=1989 |title=Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975 |publisher=University of Minnesota Press |location=Minneapolis |isbn=9780816617869 |url=https://archive.org/details/daringtobebadrad0000echo/page/104/mode/2up }} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Fahs |first=Breanne |date=Fall 2008 |title=The radical possibilities of Valerie Solanas |journal=[[Feminist Studies]] |volume=34 |issue=3 |pages=591–617 |jstor=20459223 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Frank |first=Marcie |year=1996 |chapter=Popping off Warhol: from the gutter to the underground and beyond |pages=210–223 |editors=Jennifer Doyle, Jonathan Flatley & José Esteban Muñoz |title=Pop Out: Queer Warhol |location=Durham, NC |publisher=Duke University Press |isbn=978-0-8223-1741-8 |ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=Fahs |first=Breanne |year=2014 |title=Valerie Solanas: The Defiant Life of the Woman Who Wrote SCUM (and Shot Andy Warhol) |publisher=The Feminist Press |location=New York |url=https://www.feministpress.org/books-n-z/valer |isbn=978-1558618480 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Frank |first=Marcie |year=1996 |chapter=Popping off Warhol: from the gutter to the underground and beyond |pages=[https://archive.org/details/popoutqueerwarho00jenn/page/210 210–223] |editor1-first=Jennifer |editor1-last=Doyle |editor2-first=Jonathan |editor2-last=Flatley |editor3-first=José Esteban |editor3-last=Muñoz |title=Pop Out: Queer Warhol |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/popoutqueerwarho00jenn |chapter-url-access=registration |location=Durham, NC |publisher=Duke University Press |isbn=978-0-8223-1741-8 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Friedan |first=Betty |year=1998 |origyear=1963 |title=It Changed My Life: Writings on the Women's Movement |location=Cambridge, MA |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=0-674-46885-6 |ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=Friedan |first=Betty |year=1976 |title=It Changed My Life: Writings on the Women's Movement |location=New York |publisher=Random House |isbn=978-0-394-46398-8 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=Friedan |first=Betty |year=1998 |orig-year=1963 |title=It Changed My Life: Writings on the Women's Movement |location=Cambridge, MA |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-46885-6 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=Hamilton |first=Neil A. |year=2002 |title=Rebels and Renegades: a Chronology of Social and Political Dissent in the United States |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-0-415-93639-2 }} |

||

* {{cite |

* {{cite book |last=Harding |first=James Martin |year=2010 |title=Cutting Performances: Collage Events, Feminist Artists, and the American Avant-Garde |location=Ann Arbor |publisher=University of Michigan Press |isbn=978-0-472-11718-5 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=Harron |first=Mary |year=1996 |chapter=Introduction: on Valerie Solanas |pages=[https://archive.org/details/ishotandywarhol00harr/page/ vii–xxxi] |editor1-first=Mary |editor1-last=Harron |editor2-first=Daniel |editor2-last=Minahan |title=I Shot Andy Warhol |location=New York |publisher=Grove Press |isbn=978-0-8021-3491-2 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/ishotandywarhol00harr/page/ }} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Heller |first=Dana |year=2001 |title=Shooting Solanas: radical feminist history and the technology of failure |journal=[[Feminist Studies]] |volume=27 |issue=1 |pages=167–189 |jstor=3178456 |doi=10.2307/3178456 |hdl=2027/spo.0499697.0027.113 |hdl-access=free }} |