Angola: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 99.246.30.79 (talk) to last version by EvergreenFir |

→Politics: Updated the Ibrahim Index of African Governance info to 2013 report (edited with ProveIt) |

||

| Line 180: | Line 180: | ||

Angola is classified as 'not free' by [[Freedom House]] in the [[Freedom in the World]] 2013 report.<ref name=freedomhouse>{{cite web|title=Angola|url=http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2013/angola|work=Freedom in the World 2013|publisher=Freedom House|accessdate=27 July 2013}}</ref> The report noted that the [[Angolan legislative election, 2012|August 2012 parliamentary elections]], in which the ruling [[Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola]] won more than 70% of the vote, suffered from serious flaws, including outdated and inaccurate voter rolls.<ref name=freedomhouse/> Voter turnout dropped from 80% in 2008 to 60%.<ref name=freedomhouse/> |

Angola is classified as 'not free' by [[Freedom House]] in the [[Freedom in the World]] 2013 report.<ref name=freedomhouse>{{cite web|title=Angola|url=http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2013/angola|work=Freedom in the World 2013|publisher=Freedom House|accessdate=27 July 2013}}</ref> The report noted that the [[Angolan legislative election, 2012|August 2012 parliamentary elections]], in which the ruling [[Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola]] won more than 70% of the vote, suffered from serious flaws, including outdated and inaccurate voter rolls.<ref name=freedomhouse/> Voter turnout dropped from 80% in 2008 to 60%.<ref name=freedomhouse/> |

||

Angola scored poorly on the |

Angola scored poorly on the 2013 [[Ibrahim Index of African Governance]]. It was ranked 39 out of 52 [[sub-Saharan Africa]]n countries, scoring particularly badly in the areas of Participation and Human Rights, Sustainable Economic Opportunity and Human Development. The Ibrahim Index uses a number of different variables to compile its list which reflects the state of governance in Africa.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.moibrahimfoundation.org/iiag/ | title=Ibrahim Index of African Governance | Mo Ibrahim Foundation | publisher=Mo Ibrahim Foundation | accessdate=9 August 2014}}</ref> |

||

The new [[Constitution of Angola|constitution]], adopted in 2010, further sharpened the authoritarian character of the regime. In the future, there will be no presidential elections: the president and the vice-president of the political party which comes out strongest in the parliamentary elections become automatically president and vice-president of Angola.<ref>In this manner, [[José Eduardo dos Santos]] is now finally in a legal situation. As he had obtained a relative, but not the absolute majority of votes in the 1992 presidential election, a second round—opposing him to [[Jonas Savimbi]]—was constitutionally necessary to make his election effective, but he preferred never to hold this second round.</ref> Through a variety of mechanisms, the state president controls all the other organs of the state, so that the principle of the division of power is not maintained. As a consequence, Angola has no longer a presidential system, in the sense of the systems existing e.g. in the [[Federal government of the United States|USA]] or in [[French government|France]]. In terms of the classifications used in constitutional law, its regime is considered one of several authoritarian regimes in Africa.<ref>See Jorge Miranda, ''A Constituição de Angola de 2010'', published in the academic journal ''O Direito'' (Lisbon), vol. 142, 2010 – 1 (June).</ref> |

The new [[Constitution of Angola|constitution]], adopted in 2010, further sharpened the authoritarian character of the regime. In the future, there will be no presidential elections: the president and the vice-president of the political party which comes out strongest in the parliamentary elections become automatically president and vice-president of Angola.<ref>In this manner, [[José Eduardo dos Santos]] is now finally in a legal situation. As he had obtained a relative, but not the absolute majority of votes in the 1992 presidential election, a second round—opposing him to [[Jonas Savimbi]]—was constitutionally necessary to make his election effective, but he preferred never to hold this second round.</ref> Through a variety of mechanisms, the state president controls all the other organs of the state, so that the principle of the division of power is not maintained. As a consequence, Angola has no longer a presidential system, in the sense of the systems existing e.g. in the [[Federal government of the United States|USA]] or in [[French government|France]]. In terms of the classifications used in constitutional law, its regime is considered one of several authoritarian regimes in Africa.<ref>See Jorge Miranda, ''A Constituição de Angola de 2010'', published in the academic journal ''O Direito'' (Lisbon), vol. 142, 2010 – 1 (June).</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:41, 9 August 2014

Republic of Angola República de Angola (Portuguese) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Angola Avante! (Portuguese) Forward Angola! | |

Location of Angola (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Luanda |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2000) | |

| Demonym(s) | Angolan |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic |

| José Eduardo dos Santos | |

| Manuel Vicente | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• from Portugal | 11 November 1975 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,246,700 km2 (481,400 sq mi) (23rd) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 18,498,000[1][2] |

• Density | 14.8/km2 (38.3/sq mi) (199th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $139.059 billion[3] (64th) |

• Per capita | $6,484[3] (107th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $129.785 billion[3] (61st) |

• Per capita | $6,052[3] (91st) |

| Gini (2009) | 42.7[4] medium |

| HDI (2013) | low (149th) |

| Currency | Kwanza (AOA) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (not observed) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +244 |

| ISO 3166 code | AO |

| Internet TLD | .ao |

Angola /ænˈɡoʊlə/, officially the Republic of Angola (Portuguese: República de Angola pronounced [ʁɛˈpublikɐ dɨ ɐ̃ˈɡɔlɐ]; Kikongo, Kimbundu, Umbundu: Repubilika ya Ngola), is a country in Southern Africa bordered by Namibia on the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the north, and Zambia on the east; its west coast is on the Atlantic Ocean and Luanda is its capital city. The exclave province of Cabinda has borders with the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Portuguese were present in some – mostly coastal – points of the territory of what is now Angola, from the 16th to the 19th century, interacting in diverse ways with the peoples who lived there. In the 19th century, they slowly and hesitantly began to establish themselves in the interior. Angola as a Portuguese colony encompassing the present territory was not established before the end of the 19th century, and "effective occupation", as required by the Berlin Conference (1884) was achieved only by the 1920s after the Mbunda resistance and abduction of their King, Mwene Mbandu I Lyondthzi Kapova.[6] Independence was achieved in 1975, after a protracted liberation war. After independence, Angola was the scene of an intense civil war from 1975 to 2002. Despite the civil war, areas such as Baixa de Cassanje continue a lineage of kings which have included the former King Kambamba Kulaxingo and current King Dianhenga Aspirante Mjinji Kulaxingo.

The country has vast mineral and petroleum reserves, and its economy has on average grown at a double-digit pace since the 1990s, especially since the end of the civil war. In spite of this, standards of living remain low for the majority of the population, and life expectancy and infant mortality rates in Angola are among the worst in the world.[7] Angola is considered to be economically disparate, with the majority of the nation's wealth concentrated in a disproportionately small sector of the population.

Angola is a member state of the African Union, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, the Latin Union and the Southern African Development Community.

Etymology

The name Angola comes from the Portuguese colonial name Reino de Angola (Kingdom of Angola), appearing as early as Dias de Novais's 1571 charter.[8] The toponym was derived by the Portuguese from the title ngola held by the kings of Ndongo. Ndongo was a kingdom in the highlands, between the Kwanza and Lukala Rivers, nominally tributary to the king of Kongo but which was seeking greater independence during the 16th century.

History

Early migrations and political units

Khoisan hunter-gatherers are the earliest known modern human inhabitants of the area. They were largely absorbed and/or replaced by Bantu peoples during the Bantu migrations, though small numbers remain in parts of southern Angola to the present day. The Bantu came from the north, probably from somewhere near the present-day Republic of Cameroon and Sudan.[9] The establishment of the Bantu took many centuries and gave rise to various groups who took on different ethnic characteristics.

During this time, the Bantu established a number of political units ("kingdoms", "empires") in most parts of what today is Angola. The best known of these is the Kingdom of the Kongo that had its centre in the northwest of contemporary Angola, but included important regions in the west of present day Democratic Republic of the Congo and Republic of Congo, and in southern Gabon. It established trade routes with other trading cities and civilizations up and down the coast of southwestern and West Africa and even with the Great Zimbabwe Mutapa Empire, but engaged in little or no transoceanic trade.[10]

Others include the Mbunda, whose Kingdom was established in the fifteenth century[11] at the confluence of Kwilu and Kasai rivers, in the south of present day Democratic Republic of the Congo, after a misunderstanding in Kola, also known as the origin of the Lunda and the Luba Kingdoms. The Mbunda trace their origin from Sudan,[12] trekking southwards through Kola where they came in contact with the Luba and Ruund Kingdoms. They reached what is now Angola in the sixteenth century, where they encountered the Khoisan, Bushmen and other groups considerably less technologically advanced than themselves, whom they easily dominated with their superior knowledge of metal-working, ceramics and agriculture. The Mbunda Kingdom in Mbundaland, southeast of the now Angola endured until late nineteenth century, one of the oldest and biggest ethnic grouping in Southern Africa.[13]

Portuguese colonization

The geographical areas now designated as Angola entered into contact with the Portuguese in the late 15th century, concretely in 1483, when Portugal established relations with the Kongo State, which stretched from modern Gabon in the north to the Kwanza River in the south. In this context, the Portuguese established a small trade-post at the port of Mpinda, in Soyo. The Portuguese explorer Paulo Dias de Novais founded Luanda in 1575 as "São Paulo de Loanda", with a hundred families of settlers and four hundred soldiers. Benguela, a Portuguese fort from 1587 which became a town in 1617, was another important early settlement they founded and ruled. The Portuguese would establish several settlements, forts and trading posts along the coastal strip of current-day Angola, which relied on the slave trade, commerce in raw materials, and the exchange of goods for survival.

The Atlantic slave trade provided a large number of black slaves to merchants and to slave dealers in Angola.[14] European traders would export manufactured goods to the coast of Africa where they would be exchanged for slaves. Within the Portuguese Empire, most black African slaves were traded to Portuguese merchants who bought them to sell as cheap labour for use on Brazilian agricultural plantations. This trade would last until the first half of the 19th century. According to John Iliffe, "Portuguese records of Angola from the 16th century show that a great famine occurred on average every seventy years; accompanied by epidemic disease, it might kill one-third or one-half of the population, destroying the demographic growth of a generation and forcing colonists back into the river valleys".[15]

The Portuguese gradually took control of the coastal strip during the 16th century by a series of treaties and wars, forming the Portuguese colony of Angola. Taking advantage of the Portuguese Restoration War, the Dutch occupied Luanda from 1641 to 1648, where they allied with local peoples, consolidating their colonial rule against the remaining Portuguese resistance. In 1648, a fleet under the command of Salvador de Sá retook Luanda for Portugal and initiated a conquest of the lost territories, which restored Portugal to its former possessions by 1650. Treaties regulated relations with Kongo in 1649 and Njinga's Kingdom of Matamba and Ndongo in 1656. The conquest of Pungo Andongo in 1671 was the last major Portuguese expansion from Luanda outwards, as attempts to invade Kongo in 1670 and Matamba in 1681 failed. Portugal also expanded its territory behind the colony of Benguela to some extent, but until the 19th century the inroads from Luanda and Benguela were very limited, and Portugal had neither the intention nor the means to carry out a large scale territorial occupation and colonization.

The process resulted in few gains until the 1880s. Development of the hinterland began after the Berlin Conference in 1885 fixed the colony's borders, and British and Portuguese investment fostered mining, railways, and agriculture based on various forced-labour systems. Full Portuguese administrative control of the hinterland did not establish itself until the beginning of the 20th century, after the Mbunda resistance and abduction of their King, Mwene Mbandu I Lyondthzi Kapova,[6] eventually dislodged the Mbunda Kingdom extending Angolan territory over Mbundaland.[13] In 1951 the Portuguese government designated the colony as an overseas province of Portugal, called the Overseas Province of Angola.

Portugal had a minimalist presence in Angola for nearly five hundred years, and early calls for independence provoked little reaction amongst the population. More overtly political organisations first appeared in the 1950s and began to make organised demands for self-determination, especially in international forums such as the Non-Aligned Movement.

The Portuguese regime, meanwhile, refused to accede to the demands for independence, provoking an armed conflict that started in 1961 when black guerrillas attacked both white and black civilians in cross-border operations in northeastern Angola. The war came to be known as the Colonial War. In this struggle, the principal protagonists included, the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), founded in 1956, the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), which appeared in 1961 and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), founded in 1966.

After many years of conflict that led to the weakening of all the insurgent parties, Angola gained its independence on 11 November 1975, after the 1974 coup d'état in Lisbon, Portugal, which overthrew the Portuguese regime headed by Marcelo Caetano.

Portugal's new revolutionary leaders began in 1974 a process of political change at home and accepted independence for its former colonies abroad. In Angola a fight for dominance broke out immediately between the three nationalist movements. The events prompted a mass exodus of Portuguese citizens, creating up to 300 000 destitute Portuguese refugees—the retornados.[16] The new Portuguese government tried to mediate an understanding between the three competing movements, and succeeded in getting them to agree, on paper, to form a common government. But in the end none of the African parties respected the commitments made, and military force resolved the issue.

Independence and civil war

After independence in November 1975, Angola faced a devastating civil war which lasted several decades and claimed millions of lives and produced many refugees.[17] Following negotiations held in Portugal, itself under severe social and political turmoil and uncertainty due to the April 1974 revolution, Angola's three main guerrilla groups agreed to establish a transitional government in January 1975.

Within two months, however, the FNLA, MPLA and UNITA were fighting each other and the country was well on its way to being divided into zones controlled by rival armed political groups. The superpowers were quickly drawn into the conflict, which became a flash point for the Cold War. The United States, Zaire (today's Democratic Republic of the Congo) and South Africa supported the FNLA and UNITA.[18][19] The Soviet Union and Cuba supported the MPLA.

In the beginning of the Civil War, most of the half million Portuguese that lived in Angola and accounted for the majority of the skilled work in the public administration, agriculture, industries and trade fled the country leaving its once prosperous and growing economy to a state of bankruptcy.[20]

During most of this period, 1975–1990, the MPLA organised and maintained a socialist regime.[21]

Ceasefire with UNITA

On 22 March 2002, Jonas Savimbi, the leader of UNITA, was killed in combat with government troops. A cease-fire was reached by the two factions shortly afterwards.[22] UNITA gave up its armed wing and assumed the role of major opposition party, although in the knowledge that in the present regime a legitimate democratic election was impossible. Although the political situation of the country began to stabilize, regular democratic processes were not established before the Elections in Angola in 2008 and 2012 and the adoption of a new Constitution of Angola in 2010, all of which strengthened the prevailing Dominant-party system. MPLA head officials continue e.g. to be given senior positions in top level companies or other fields, although a few outstanding UNITA figures are given some shares in the economic as well as in the military share.[23]

Among Angola's major problems are a serious humanitarian crisis (a result of the prolonged war), the abundance of minefields, the continuation of the political, and to a much lesser degree, military activities in favour of the independence of the northern exclave of Cabinda, carried out in the context of the protracted Cabinda Conflict by the Frente para a Libertação do Enclave de Cabinda, but most of all, the dilapidation of the country's rich mineral resources by the regime. While most of the internally displaced have now settled around the capital, in the so-called "Musseques", the general situation for Angolans remains desperate.[24]

Geography

At 481,321 square miles (1,246,620 km2),[25] Angola is the world's twenty-third largest country. It is comparable in size to Mali, or twice the size of France or Texas. It lies mostly between latitudes 4° and 18°S, and longitudes 12° and 24°E.

Angola is bordered by Namibia to the south, Zambia to the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north-east, and the South Atlantic Ocean to the west. The coastal exclave of Cabinda in the north, borders the Republic of the Congo to the north, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south.[26] Angola's capital, Luanda, lies on the Atlantic coast in the northwest of the country.

Climate

Angola has three seasons, a dry season which lasts from May to October, a transitional season with some rain from November to January and a hot rainy season from February to April. April is the wettest month.[27][28] Angola's average temperature on the coast is 60 °F (16 °C) in the winter and 70 °F (21 °C) in the summer, while the interior is generally hotter and dryer.

Politics

Angola's motto is Virtus Unita Fortior, a Latin phrase meaning "Virtue is stronger when united". The executive branch of the government is composed of the President, the Vice-Presidents and the Council of Ministers. For decades, political power has been concentrated in the Presidency.

Governors of the 18 provinces are appointed by the president. The Constitutional Law of 1992 establishes the broad outlines of government structure and delineates the rights and duties of citizens. The legal system is based on Portuguese and customary law but is weak and fragmented, and courts operate in only 12 of more than 140 municipalities. A Supreme Court serves as the appellate tribunal; a Constitutional Court with powers of judicial review has not been constituted until 2010, despite statutory authorization.

After the end of the Civil War the regime came under pressure from within as well as from the international environment, to become more democratic and less authoritarian. Its reaction was to operate a number of changes without substantially changing its character.[29]

Angola is classified as 'not free' by Freedom House in the Freedom in the World 2013 report.[30] The report noted that the August 2012 parliamentary elections, in which the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola won more than 70% of the vote, suffered from serious flaws, including outdated and inaccurate voter rolls.[30] Voter turnout dropped from 80% in 2008 to 60%.[30]

Angola scored poorly on the 2013 Ibrahim Index of African Governance. It was ranked 39 out of 52 sub-Saharan African countries, scoring particularly badly in the areas of Participation and Human Rights, Sustainable Economic Opportunity and Human Development. The Ibrahim Index uses a number of different variables to compile its list which reflects the state of governance in Africa.[31]

The new constitution, adopted in 2010, further sharpened the authoritarian character of the regime. In the future, there will be no presidential elections: the president and the vice-president of the political party which comes out strongest in the parliamentary elections become automatically president and vice-president of Angola.[32] Through a variety of mechanisms, the state president controls all the other organs of the state, so that the principle of the division of power is not maintained. As a consequence, Angola has no longer a presidential system, in the sense of the systems existing e.g. in the USA or in France. In terms of the classifications used in constitutional law, its regime is considered one of several authoritarian regimes in Africa.[33]

Military

The Angolan Armed Forces (AAF) is headed by a Chief of Staff who reports to the Minister of Defense. There are three divisions—the Army (Exército), Navy (Marinha de Guerra, MGA), and National Air Force (Força Aérea Nacional, FAN). Total manpower is about 110,000.[citation needed] Its equipment includes Russian-manufactured fighters, bombers, and transport planes. There are also Brazilian-made EMB-312 Tucano for training role, Czech-made L-39 for training and bombing role, Czech Zlin for training role and a variety of western made aircraft such as C-212\Aviocar, Sud Aviation Alouette III, etc. A small number of AAF personnel are stationed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) and the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville).

Police

The National Police departments are Public Order, Criminal Investigation, Traffic and Transport, Investigation and Inspection of Economic Activities, Taxation and Frontier Supervision, Riot Police and the Rapid Intervention Police. The National Police are in the process of standing up an air wing, which will provide helicopter support for operations. The National Police are developing their criminal investigation and forensic capabilities. The force has an estimated 6,000 patrol officers, 2,500 taxation and frontier supervision officers, 182 criminal investigators and 100 financial crimes detectives and around 90 economic activity inspectors.[citation needed]

The National Police have implemented a modernization and development plan to increase the capabilities and efficiency of the total force. In addition to administrative reorganization, modernization projects include procurement of new vehicles, aircraft and equipment, construction of new police stations and forensic laboratories, restructured training programs and the replacement of AKM rifles with 9 mm Uzis for officers in urban areas.

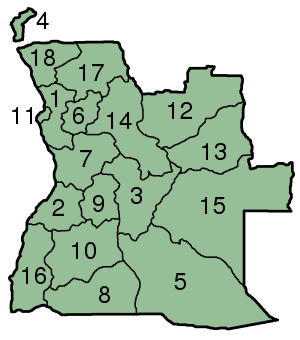

Administrative divisions

Angola is divided into eighteen provinces (províncias) and 163 municipalities.[34] The municipalities are further divided into 475 communes (townships).[35] The provinces are:

|

|

Exclave of Cabinda

With an area of approximately 7,283 square kilometres (2,812 sq mi), the Northern Angolan province of Cabinda is unusual in being separated from the rest of the country by a strip, some 60 kilometres (37 mi) wide, of the Democratic Republic of Congo along the lower Congo river. Cabinda borders the Congo Republic to the north and north-northeast and the DRC to the east and south. The town of Cabinda is the chief population center.

According to a 1995 census, Cabinda had an estimated population of 600,000, approximately 400,000 of whom live in neighboring countries. Population estimates are, however, highly unreliable. Consisting largely of tropical forest, Cabinda produces hardwoods, coffee, cocoa, crude rubber and palm oil. The product for which it is best known, however, is its oil, which has given it the nickname, "the Kuwait of Africa". Cabinda's petroleum production from its considerable offshore reserves now accounts for more than half of Angola's output.[36] Most of the oil along its coast was discovered under Portuguese rule by the Cabinda Gulf Oil Company (CABGOC) from 1968 onwards.

Ever since Portugal handed over sovereignty of its former overseas province of Angola to the local independence groups (MPLA, UNITA, and FNLA), the territory of Cabinda has been a focus of separatist guerrilla actions opposing the Government of Angola (which has employed its military forces, the FAA—Forças Armadas Angolanas) and Cabindan separatists. The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda-Armed Forces of Cabinda (FLEC-FAC) announced a virtual Federal Republic of Cabinda under the Presidency of N'Zita Henriques Tiago. One of the characteristics of the Cabindan independence movement is its constant fragmentation, into smaller and smaller factions.

Economy

Angola's financial system is maintained by the National Bank of Angola and managed by Governor Jose de Lima Massano. Angola has a rich subsoil heritage, from diamonds, oil, gold, copper, and a rich wildlife (dramatically impoverished during the civil war), forest, and fossils. Since independence, oil and diamonds have been the most important economic resource. Smallholder and plantation agriculture have dramatically dropped because of the Angolan Civil War, but have begun to recover after 2002. The transformation industry that had come into existence in the late colonial period collapsed at independence, because of the exodus of most of the ethnic Portuguese population, but has begun to reemerge (with updated technologies), partly because of the influx of new Portuguese entrepreneurs. Similar developments can be verified in the service sector.

Overall, Angola's economy has undergone a period of transformation in recent years, moving from the disarray caused by a quarter century of civil war to being the fastest growing economy in Africa and one of the fastest in the world, with an average GDP growth of 20 percent between 2005 and 2007.[37] In the period 2001–2010, Angola had the world's highest annual average GDP growth, at 11.1 percent. In 2004, China's Eximbank approved a $2 billion line of credit to Angola. The loan is being used to rebuild Angola's infrastructure, and has also limited the influence of the International Monetary Fund in the country.[38] China is Angola's biggest trade partner and export destination as well as the fourth-largest importer. Bilateral trade reached $27.67 billion in 2011, up 11.5 percent year-on-year. China's imports, mainly crude oil and diamonds, increased 9.1 percent to $24.89 billion while China's exports, including mechanical and electrical products, machinery parts and construction materials, surged 38.8 percent.[citation needed] The overabundance of oil led to a local unleaded gasoline "pricetag" of £0.37 per gallon.[39]

The Economist reported in 2008 that diamonds and oil make up 60 percent of Angola's economy, almost all of the country's revenue and are its dominant exports.[40] Growth is almost entirely driven by rising oil production which surpassed 1.4 million barrels per day (220,000 m3/d) in late 2005 and was expected to grow to 2 million barrels per day (320,000 m3/d) by 2007. Control of the oil industry is consolidated in Sonangol Group, a conglomerate which is owned by the Angolan government. In December 2006, Angola was admitted as a member of OPEC.[41] However, operations in diamond mines include partnerships between state-run Endiama and mining companies such as ALROSA which continue operations in Angola.[42] The economy grew 18% in 2005, 26% in 2006 and 17.6% in 2007. However, due to the global recession the economy contracted an estimated −0.3% in 2009.[43] The security brought about by the 2002 peace settlement has led to the resettlement of 4 million displaced persons, thus resulting in large-scale increases in agriculture production.

Although the country's economy has developed significantly since achieving political stability in 2002, mainly thanks to the fast-rising earnings of the oil sector, Angola faces huge social and economic problems. These are in part a result of the almost continual state of conflict from 1961 onwards, although the highest level of destruction and socio-economic damage took place after the 1975 independence, during the long years of civil war. However, high poverty rates and blatant social inequality are chiefly the outcome of a combination of a persistent political authoritarianism, of "neo-patrimonial" practices at all levels of the political, administrative, military, and economic apparatuses, and of a pervasive corruption.[44] The main beneficiary of this situation is a social segment constituted since 1975, but mainly during the last decades, around the political, administrative, economic, and military power holders, which has accumulated (and continues accumulating) enormous wealth.[45] "Secondary beneficiaries" are the middle strata which are about to become social classes. However, overall almost half the population has to be considered as poor, but in this respect there are dramatic differences between the countryside and the cities (where by now slightly more than 50% of the people live).

An inquiry carried out in 2008 by the Angolan Instituto Nacional de Estatística has it that in the rural areas roughly 58% must be classified as "poor", according to UN norms, but in the urban areas only 19%, while the overall rate is 37%.[46] In the cities, a majority of families, well beyond those officially classified as poor, have to adopt a variety of survival strategies.[47] At the same time, in urban areas social inequality is most evident, and assumes extreme forms in the capital, Luanda.[48] In the Human Development Index Angola constantly ranks in the bottom group.[49]

According to The Heritage Foundation, a conservative American think tank, oil production from Angola has increased so significantly that Angola now is China's biggest supplier of oil.[50] Growing oil revenues have also created opportunities for corruption: according to a recent Human Rights Watch report, 32 billion US dollars disappeared from government accounts from 2007 to 2010.[51]

Before independence in 1975, Angola was a breadbasket of southern Africa and a major exporter of bananas, coffee and sisal, but three decades of civil war (1975–2002) destroyed the fertile countryside, leaving it littered with landmines and driving millions into the cities. The country now depends on expensive food imports, mainly from South Africa and Portugal, while more than 90 percent of farming is done at family and subsistence level. Thousands of Angolan small-scale farmers are trapped in poverty.[52]

The enormous differences between the regions pose a serious structural problem in the Angolan economy. This is best illustrated by the fact that about one third of the economic activities is concentrated in Luanda and the neighbouring Bengo province, while several areas of the interior are characterized by stagnation and even regression.[53]

One of the economic consequences of the social and regional disparities is a sharp increase in Angolan private investments abroad. The small fringe of Angolan society where most of the accumulation takes place seeks to spread its assets, for reasons of security and profit. For the time being, the biggest share of these investments is concentrated in Portugal where the Angolan presence (including that of the family of the state president) in banks as well as in the domains of energy, telecommunications, and mass media has become notable, as has the acquisition of vineyards and orchards as well as of touristic enterprises.[54]

Transport

Transport in Angola consists of:

- Three separate railway systems totalling 2,761 km (1,715 mi)

- 76,626 km (47,613 mi) of highway of which 19,156 km (11,903 mi) is paved

- 1,295 navigable inland waterways

- Eight major sea ports

- 243 airports, of which 32 are paved.

Travel on highways outside of towns and cities in Angola (and in some cases within) is often not best advised for those without four-by-four vehicles. While a reasonable road infrastructure has existed within Angola, time and the war have taken their toll on the road surfaces, leaving many severely potholed, littered with broken asphalt. In many areas drivers have established alternate tracks to avoid the worst parts of the surface, although careful attention must be paid to the presence or absence of landmine warning markers by the side of the road. The Angolan government has contracted the restoration of many of the country's roads. The road between Lubango and Namibe, for example, was completed recently with funding from the European Union, and is comparable to many European main routes. Progress to complete the road infrastructure is likely to take some decades, but substantial efforts are already being made in the right directions.

Demographics

Angola's population is estimated to be 18,056,072 (2012).[55] It is composed of Ovimbundu (language Umbundu) 37%, Ambundu (language Kimbundu) 25%, Bakongo 13%, and 32% other ethnic groups (including the Chokwe, the Ovambo, the Mbunda, with the latter having been replaced by Ganguela, a generic term for peoples east of the Central Highlands,[56] which has a slightly derogatory meaning when applied by the western ethnic groups,[57] and the Xindonga) as well as about 2% mestiços (mixed European and African), 1.4% Chinese and 1% European.[58] The Ambundu and Ovimbundu nations combined form a majority of the population, at 62%.[59] The population is forecast to grow to over 47 million people to 2060, nearly tripling the estimated 16 to 18 million in 2011.[60] The last official census was taken in 1970, and showed the total population as being 5.6 million.[61] The first post-independence census is to be held in 2014.

It is estimated that Angola was host to 12,100 refugees and 2,900 asylum seekers by the end of 2007. 11,400 of those refugees were originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who arrived in the 1970s.[62] As of 2008 there were an estimated 400,000 Democratic Republic of the Congo migrant workers,[63] at least 30,000 Portuguese,[64] and about 259,000 Chinese living in Angola.[65]

Since 2003, more than 400,000 Congolese migrants have been expelled from Angola.[66] Prior to independence in 1975, Angola had a community of approximately 350,000 Portuguese;[67] currently, there are about 200,000 who are registered with the consulates, and increasing due to the debt crisis in Portugal.[68] The Chinese population stands at 258,920, mostly composed of temporary migrants.[69]

The total fertility rate of Angola is 5.54 children born per woman (2012 estimates), the 11th highest in the world.[70]

Languages

The languages in Angola are those originally spoken by the different ethnic groups and Portuguese, introduced during the Portuguese colonial era. The indigenous languages with the largest usage are Umbundu, Kimbundu, and Kikongo, in that order. Portuguese is the official language of the country.

Mastery of the official language is probably more extended in Angola than it is elsewhere in Africa, and this certainly applies to its use in everyday life. Moreover, and above all, the proportion of native (or near native) speakers of the language of the former colonizer, turned official after independence, is no doubt considerably higher than in any other African country.[citation needed]

There are three intertwined historical reasons for this situation.

- In the Portuguese "bridgeheads" Luanda and Benguela, which existed on the coast of what today is Angola since the 15th and 16th century, respectively, Portuguese was spoken not only by the Portuguese and their mestiço descendents, but—especially in and around Luanda—by a significant number of Africans, although these always remained native speakers of their local African language.

- Since the Portuguese conquest of the present territory of Angola, and especially since its "effective occupation" in the mid-1920s, schooling in Portuguese was slowly developed by the colonial state as well as by Catholic and Protestant missions. The rhythm of this expansion was considerably accelerated during the late colonial period, 1961–1974, so that by the end of the colonial period children all over the territory (with relatively few exceptions) had at least some access to the Portuguese language.[71]

- In the same late colonial period, the legal discrimination of the black population was abolished, and the state apparatus in fields like health, education, social work, and rural development was enlarged. This entailed a significant increase in jobs for Africans, under the condition that they spoke Portuguese.

As a consequence of all this, the African “lower middle class” which at that stage formed in Luanda and other cities began to often prevent their children from learning the local African language, in order to guarantee that they learned Portuguese as their native language. At the same time, the white and “mestiço” population, where some knowledge of African languages could previously often been found, neglected this aspect more and more, to the point of frequently ignoring it totally. After independence, these tendencies continued, and were even strengthened, under the rule of the MPLA which has its main social roots exactly in those social segments where the mastery of Portuguese as well as the proportion of native Portuguese speakers was highest. This became a political side issue, as FNLA and UNITA, given their regional constituencies, came out in favour of a greater attention to the African languages, and as the FNLA favoured French over Portuguese.

The dynamics of the language situation, as described above, were additionally fostered by the massive migrations triggered by the Civil War. Ovimbundu, the most populous ethnic group and the most affected by the war, appeared in great numbers in urban areas outside their areas, especially in Luanda and surroundings. At the same time, a majority of the Bakongo who had fled to the Democratic Republic of Congo in the early 1960s, or of their children and grandchildren, returned to Angola, but mostly did not settle in their original "habitat", but in the cities—and again above all in Luanda. As a consequence, more than half the population is now living in the cities which, from the linguistic point of view, have become highly heterogeneous. This means, of course, that Portuguese as the overall language of communication is by now of paramount importance, and that the role of the African languages is steadily decreasing among the urban population—a trend which is beginning to spread into rural areas as well.

The exact numbers of those fluent in Portuguese or who speak Portuguese as a first language are unknown, although a census is expected to be carried out in July–August 2013.[72][needs update] Quite a number of voices demand the recognition of "Angolan Portuguese" as a specific variant, comparable to those spoken in Portugal or in Brazil. However, while there exists a certain number of idiomatic particularities in everyday Portuguese, as spoken by Angolans, it remains to be seen whether or not the Angolan government comes to the conclusion that these particularities constitute a configuration that justifies the claim to be a new language variant.

Religion

There are about 1000 mostly Christian religious communities in Angola.[73] While reliable statistics are nonexistent, estimates have it that more than half of the population are Catholics, while about a quarter adhere to the Protestant churches introduced during the colonial period: the Congregationalists mainly among the Ovimbundu of the Central Highlands and the coastal region to its West, the Methodists concentrating on the Kimbundu speaking strip from Luanda to Malanje, the Baptists almost exclusively among the Bakongo of the Northwest (now massively present in Luanda as well) and dispersed Adventists, Reformed and Lutherans.[74] In Luanda and region there subsists a nucleus of the "syncretic" Tocoists and in the northwest a sprinkling of Kimbanguism can be found, spreading from the Congo/Zaire. Since independence, hundreds of Pentecostal and similar communities have sprung up in the cities, where by now about 50% of the population is living; several of these communities/churches are of Brazilian origin.

The U.S. Department of State estimates the Muslim population at 80,000–90,000,[75] while the Islamic Community of Angola puts the figure closer to 500,000.[76] Muslims consist largely of migrants from West Africa and the Middle East (especially Lebanon), although some are local converts.[77] The Angolan government does not legally recognize any Muslim organizations and often shuts down mosques or prevents their construction.[78]

In a study assessing nations' levels of religious regulation and persecution with scores ranging from 0 to 10 where 0 represented low levels of regulation or persecution, Angola was scored 0.8 on Government Regulation of Religion, 4.0 on Social Regulation of Religion, 0 on Government Favoritism of Religion and 0 on Religious Persecution.[79]

Foreign missionaries were very active prior to independence in 1975, although since the beginning of the anti-colonial fight in 1961 the Portuguese colonial authorities expelled a series of Protestant missionaries and closed mission stations based on the belief that the missionaries were inciting pro-independence sentiments. Missionaries have been able to return to the country since the early 1990s, although security conditions due to the civil war have prevented them until 2002 from restoring many of their former inland mission stations.[80]

The Catholic Church and some major Protestant denominations mostly keep to themselves in contrast to the "New Churches" which actively proselytize. Catholics, as well as some major Protestant denominations, provide help for the poor in the form of crop seeds, farm animals, medical care and education.[81][82][83]

Largest cities

Template:Largest cities of Angola

Culture

In Angola, there is a Culture Ministry that is managed by Culture Minister Rosa Maria Martins da Cruz e Silva.[84][85] Portugal has been present in Angola for 400 years, occupied the territory in the 19th and early 20th century, and ruled over it for about 50 years. As a consequence, both countries share cultural aspects: language (Portuguese) and main religion (Roman Catholic Christianity). The substrate of Angolan culture is African, mostly Bantu, while Portuguese culture has been imported. The diverse ethnic communities – the Ovimbundu, Ambundu, Bakongo, Chokwe, Mbunda and other peoples – maintain to varying degrees their own cultural traits, traditions and languages, but in the cities, where slightly more than half of the population now lives, a mixed culture has been emerging since colonial times – in Luanda since its foundation in the 16th century. In this urban culture, the Portuguese heritage has become more and more dominant. An African influence is evident in music and dance, and is moulding the way in which Portuguese is spoken, but is almost disappearing from the vocabulary. This process is well reflected in contemporary Angolan literature, especially in the works of Pepetela and Ana Paula Ribeiro Tavares.

Leila Lopes, Miss Angola 2011, was crowned Miss Universe 2011 in Brazil on 12 September 2011 making her the first Angolan to win the pageant.

Health

Epidemics of cholera, malaria, rabies and African hemorrhagic fevers like Marburg hemorrhagic fever, are common diseases in several parts of the country. Many regions in this country have high incidence rates of tuberculosis and high HIV prevalence rates. Dengue, filariasis, leishmaniasis, and onchocerciasis (river blindness) are other diseases carried by insects that also occur in the region. Angola has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the world and one of the world's lowest life expectancies. A 2007 survey concluded that low and deficient niacin status was common in Angola.[86] Demographic and Health Surveys is currently conducting several surveys in Angola on malaria, domestic violence and more.[87]

Education

Although by law education in Angola is compulsory and free for eight years, the government reports that a percentage of students are not attending due to a lack of school buildings and teachers.[88] Students are often responsible for paying additional school-related expenses, including fees for books and supplies.[88]

In 1999, the gross primary enrollment rate was 74 percent and in 1998, the most recent year for which data are available, the net primary enrollment rate was 61 percent.[88] Gross and net enrollment ratios are based on the number of students formally registered in primary school and therefore do not necessarily reflect actual school attendance.[88] There continue to be significant disparities in enrollment between rural and urban areas. In 1995, 71.2 percent of children ages 7 to 14 years were attending school.[88] It is reported that higher percentages of boys attend school than girls.[88] During the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), nearly half of all schools were reportedly looted and destroyed, leading to current problems with overcrowding.[88]

The Ministry of Education hired 20,000 new teachers in 2005 and continued to implement teacher trainings.[88] Teachers tend to be underpaid, inadequately trained, and overworked (sometimes teaching two or three shifts a day).[88] Some teachers may reportedly demand payment or bribes directly from their students.[88] Other factors, such as the presence of landmines, lack of resources and identity papers, and poor health prevent children from regularly attending school.[88] Although budgetary allocations for education were increased in 2004, the education system in Angola continues to be extremely under-funded.[88]

According to estimates by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the adult literacy rate in 2011 was 70.4%.[89] 82.9% of males and 54.2% of women are literate as of 2001.[90] Since independence from Portugal in 1975, a number of Angolan students continued to be admitted every year at high schools, polytechnical institutes, and universities in Portugal, Brazil and Cuba through bilateral agreements; in general, these students belong to the elites.

Sports

Angola is the top basketball team of FIBA Africa, and a regular competitor at the Summer Olympic Games and the FIBA World Cup. The Angola national football team qualified for the 2006 FIFA World Cup, as this was their first appearance on the World Cup finals stage. They were eliminated after one defeat and two draws in the group stage. They won 3 COSAFA Cups and finished runner up in 2011 African Nations Championship. Angola has participated in the World Women's Handball Championship for several years. The country has also appeared in the Summer Olympics for seven years and both compete and have hosted the FIRS Roller Hockey World Cup. Angola is also often believed to have historic roots in the martial art "Capoeira Angola" and "Batuque" which were practiced by enslaved African Angolans transported as part of the Atlantic slave trade.[91]

See also

References

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2009). "World Population Prospects, Table A.1" (PDF). 2008 revision. United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Population Forecast to 2060 by International Futures hosted by Google Public Data Explorer". Google.com. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Angola". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "2014 Human Development Report Summary" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2014. pp. 21–25. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ a b See René Pélissier: Les Guerres grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola (1845–1941), Montamets/Orgeval: Éditions Pélissier, 1977

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth". World Fact Book. United States Central Intelligence Agency. 2014.

- ^ Heywood, Linda M. & Thornton, John K. Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the foundation of the Americas, 1585–1660, p. 82. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ^ "The Bantu in Ancient Egypt, citing sources: Alfred M M'Imanyara 'The Restatement of Bantu Origin and Meru History' published by Longman Kenya, 1992 - Social Science - 170 pages, ISBN 9966-49-832-X". Kaa-umati.co.uk. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "The Story of Africa". BBC. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Almanac of African Peoples & Nations page 523, Social Science By Muḥammad Zuhdī Yakan, Transaction Publishers, Putgers – The State University, New Jersey, ISBN 1-56000-433-9

- ^ Terms of trade and terms of trust: the history and contexts of pre-colonial pages 104 & 105...By Achim von Oppen, LIT Verlag Münster Publishers, 1993, ISBN 3-89473-246-6, ISBN 978-3-89473-246-2

- ^ a b Robert Papstein, 1994, The History and Cultural Life of the Mbunda Speaking People, Lusaka Cheke Cultural Writers Association, ISBN 9982-03-006-X

- ^ Fleisch, Axel (2004). "Angola: Slave Trade, Abolition of". In Shillington, Kevin (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Vol. 1. Routledge. pp. 131–133. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- ^ John Iliffe (2007) Africans: the history of a continent. Cambridge University Press. p.68. ISBN 0-521-68297-5

- ^ Dismantling the Portuguese Empire, Time Magazine (Monday, 7 July 1975)

- ^ The Decolonization of Portuguese Africa: Metropolitan Revolution and the Dissolution of Empire by Norrie MacQueen – Mozambique since Independence: Confronting Leviathan by Margaret Hall, Tom Young – Author of Review: Stuart A. Notholt African Affairs, Vol. 97, No. 387 (Apr., 1998), pp. 276–278, JSTOR

- ^ "Americas Third World War: How 6 million People Were killed in CIA secret wars against third world countries". Imperial Beach, California: Information Clearing House. 16 November 1981. Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "CIA & Angolan Revolution 1975 Part 1". YouTube. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "The Economist: Flight from Angola". 16 August 1975.

- ^ M.R. Bhagavan, Angola's Political Economy 1975–1985, Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 1986.

- ^ "Introduction:Angola". Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ In 2006 a former UNITA general, Nduma, was appointed head of the general staff of the armed forces.

- ^ Lari (2004), Human Rights Watch (2005)

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook – Country Comparison :: Area". United States Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "Cabinda". Global Security. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mulenga, Henry Mubanga (1999). Southern African climate anomalies, summer rainfall and the Angola low. PhD Dissertation. University of Cape Town. OCLC 85939351.

- ^ Jury, M. R.; Matari, E .E. and Matitu, M. (2008). "Equatorial African climate

teleconnections". Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 95: 407–416. doi:10.1007/s00704-008-0018-4.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|title=at position 27 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See Didier Péclard (ed.), L'Angola dans la paix: Autoritarisme et reconversions, special issue of Politique africains (Paris), 110, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Angola". Freedom in the World 2013. Freedom House. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "Ibrahim Index of African Governance". Mo Ibrahim Foundation. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Text "Mo Ibrahim Foundation" ignored (help) - ^ In this manner, José Eduardo dos Santos is now finally in a legal situation. As he had obtained a relative, but not the absolute majority of votes in the 1992 presidential election, a second round—opposing him to Jonas Savimbi—was constitutionally necessary to make his election effective, but he preferred never to hold this second round.

- ^ See Jorge Miranda, A Constituição de Angola de 2010, published in the academic journal O Direito (Lisbon), vol. 142, 2010 – 1 (June).

- ^ "Virtual Angola Facts and Statistics". The Embassy of the Republic of Angola, UK. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Country: Political and Administrative Division". Consulado Geral da República de Angola, Região Administrativa Especial de Macau. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 12 September 2011 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Angola profile". BBC News. 22 December 2013.

- ^ Angola Financial Sector Profile: MFW4A – Making Finance Work for Africa. MFW4A. Retrieved on 9 August 2013.

- ^ "The Increasing Importance of African Oil". Power and Interest Report. 20 March 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Luanda, capital of Angola, retains title of world's most expensive for expats. Telegraph. Retrieved on 9 August 2013.

- ^ The Economist. 30 August 2008 edition. U.S. Edition. Page 46. Article on Angola, "marches toward riches and democracy?".

- ^ "Angola: Country Admitted As Opec Member". Angola Press Agency. 14 December 2006.

- ^ "angolancentenary.com" (PDF). angolancentenary.com. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ao.html retrieved 24 October 2010

- ^ Anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International rates Angola one of the 10 most corrupt countries in the world.

- ^ This process is well analyzed by authors like Christine Messiant, Tony Hodges and others. For an eloquent illustrating, see now the Angolan magazine Infra-Estruturas África 7/2010.

- ^ See Angola Exame of 12/11/2010, online http://www.exameangola.com/pt/?det=16943&id=2000&mid=.

- ^ See Cristina Udelsmann Rodrigues, O Trabalho Dignifica o Homem: Estratégias de Sobrevivência em Luanda, Lisbon: Colibri: 2006.

- ^ As an excellent illustration see Luanda: A vida na cidade dos extremos, in: Visão, 11 November 2010.

- ^ The HDI 2010 lists Angola in the 146th position among 169 countries—one position below that of Haiti. See Human Development Index and its components.

- ^ Alt, Robert. "Into Africa: China's Grab for Influence and Oil". Heritage.org. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Angola: Explain Missing Government Funds". Human Rights Watch. 20 December 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Louise Redvers, POVERTY-ANGOLA: Inter Press Service News Agency – NGOs Sceptical of Govt's Rural Development Plans retrieved 6 June 2009

- ^ See Manuel Alves da Rocha, Desigualdades e assimetrias regionais em Angola: Os factores da competitividade territorial, Luanda: Centro de Estudos e Investigação Científica da Universidade Católica de Angola, 2010.

- ^ See "A força do kwanza", Visão (Lisbon), 993, 15 May 2012, pp. 50–54

- ^ "Angola Demographics Profile 2013". Index Mundi. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ José Redinha, Etnias e culturas de Angola, Luanda: Instituto de Investigalção Científica de Angola, 1975

- ^ "Alvin W. Urquhart, ''Patterns of Settlement and Subsistence in Southwestern Angola'', National Academies Press, 1963, p 10". Books.google.co.zm. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ See ethnic map and CIA – The World Factbook – Angola

- ^ As no reliable census data exist at this stage (2011), all these numbers are rough estimates only, subject to adjustments and updates.

- ^ http://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=n4ff2muj8bh2a_&ctype=l&strail=false&nselm=h&met_y=GDP&hl=en&dl=en#ctype=l&strail=false&nselm=h&met_y=POP&fdim_y=scenario:1&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=world&idim=country:AO&hl=en&dl=en

- ^ "ANGOLA – The National Archives"

- ^ [U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. "World Refugee Survey 2008". Available Online at: http://www.refugees.org/countryreports.aspx?id=2117. pp.37]

- ^ World Refugee Survey 2008 – Angola, UNHCR. NB: This figure is highly doubtful, as it makes no clear distinction between migrant workers, refugees, and immigrants.

- ^ Angola, U.S. Department of State. NB: Estimations in 2011 put that number at 100,000, and add about 150,000 to 200,000 other Europeans and Latin Americans.

- ^ "Angola: Cerca de 259.000 chineses vivem atualmente no país". Visão. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Calls for Angola to Investigate Abuse of Congolese Migrants". Inter Press Service. 21 May 2012

- ^ See the carefully researched article by Gerald Bender & Stanley Yoder, Whites in Angola on the Eve of Independence. The Poitics of Numbers, in: Africa Today, 21 (4), 1974, pp. 23–27. Flight from Angola, The Economist , 16 August 1975 puts the number at 500,000, but this is an estimate lacking appropriate sources.

- ^ Siza, Rita (6 June 2013). "José Eduardo dos Santos diz que trabalhadores portugueses são bem-vindos em Angola". Público. Lisbon.

- ^ "Chinese 'gangsters' repatriated from Angola", Telegraph

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook". United States Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ An illustration is Franz-Wilhelm Heimer, '’Educação e sociedade nas áreas rurais de Angola: Resultados de um inquérito’’, vol. 2, ‘’Análise do universo agrícola’’ (survey report), Serviços de Planeamento e Integração Económica de Angola, Luanda, 1974

- ^ "Angola: Population Census Dates Set". PARIS21. 19 April 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

Angola has set dates for their population census: from 16 July to 18 August 2013

- ^ See Fátima Viegas, Panorama das Religiões em Angola Independente (1975–2008), Ministério da Cultura/Instituto Nacional para os Assuntos Religiosos, Luanda 2008

- ^ Benedict Schubert: Der Krieg und die Kirchen: Angola 1961–1991. Exodus, Luzern/Switzerland, 1997; Lawrence W. Henderson, The Church in Angola: A river of many currents, Cleveland: Pilgrim Press, 1989

- ^ "Angola". State.gov. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ O Pais, Surgimento do Islão em Angola, 2 September 2011, Pg 18

- ^ Oyebade, Adebayo O. Culture And Customs of Angola, 2006. Pages 45–46.

- ^ "ANGOLA 2012 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT" (PDF).

- ^ Angola: Religious Freedom Profile at the Association of Religion Data Archives Brian J Grim and Roger Finke. "International Religion Indexes: Government Regulation, Government Favoritism, and Social Regulation of Religion". Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. 2 (2006) Article 1: www.religjournal.com.

- ^ "U.S. Department of State". State.gov. 1 January 2004. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Culture and customs of Angola. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. 2007. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-313-33147-3. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "International Grants 2005" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Angola Press – Leisure & Culture – Country needs modern, dynamic culture – minister. Portalangop.co.ao (28 June 2013). Retrieved on 9 August 2013.

- ^ Ministério da Cultura – República de Angola. Mincultura.gv.ao. Retrieved on 9 August 2013.

- ^ Seal AJ, Creeke PI, Dibari F; et al. (January 2007). "Low and deficient niacin status and pellagra are endemic in postwar Angola". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85 (1): 218–24. PMID 17209199.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Angola Surveys,

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Botswana". 2005 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2006). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. [dead link]

- ^ "National adult literacy rates (15+), youth literacy rates (15–24) and elderly literacy rates (65+)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

- ^ "Angola – Statistics". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Capoeira – Ponciano Almeida – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 9 August 2013.

- Much of the material in this article comes from the CIA World Factbook 2000 and the 2003 U.S. Department of State website. The information given there is however, corrected and updated on the basis of the other sources indicated.

External links

- Template:Pt icon Official website

- "Angola". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Angola at Curlie

- Angola from UCB Libraries GovPubs.

- Angola profile from the BBC News.

Wikimedia Atlas of Angola

- Key Development Forecasts for Angola from International Futures.

- National Language Mbunda

- The Mbunda Kingdom Research and Advisory Council

- StudentPulse 2010 article on challenges facing Angola

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2012 – Angola Country Report

- Markus Weimer, "The Peace Dividend: Analysis of a Decade of Angolan Indicators, 2002–2012".

|

- Angola

- Countries in Africa

- Bantu countries and territories

- Former Portuguese colonies

- Least developed countries

- Member states of OPEC

- Member states of the African Union

- Member states of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries

- Member states of the United Nations

- Portuguese-speaking countries and territories

- Republics

- States and territories established in 1975

- Central African countries

- World Digital Library related