Diferencia entre revisiones de «Usuario:Calimeronte/taller»

m (GR) Duplicate: File:Franz Kafka, handwriting.jpg → File:Kafka's notebook.JPG Exact or scaled-down duplicate: c::File:Kafka's notebook.JPG |

|||

| (No se muestran 39 ediciones intermedias de 5 usuarios) | |||

| Línea 15: | Línea 15: | ||

* [http://www.mahj.org/ Museo de Arte y de Historia del Judaísmo, París] |

* [http://www.mahj.org/ Museo de Arte y de Historia del Judaísmo, París] |

||

* [http://www.thejewishmuseum.org/ Museo de Arte Judío, Nueva York] |

* [http://www.thejewishmuseum.org/ Museo de Arte Judío, Nueva York] |

||

* [[5]] |

|||

* [[6]] |

|||

====DATUM==== |

====DATUM==== |

||

| Línea 28: | Línea 25: | ||

*Mishné Torá, Lisboa, '''1472'''. Facsimile of the colophon of the Lisbon Mishneh Torah written by the scribe Solomon ibn Alzuk and completed in 1471-72. The British Library, London, Harley Ms. 5699, fol. 434v. [http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/maimonides/exhibit1.html] |

*Mishné Torá, Lisboa, '''1472'''. Facsimile of the colophon of the Lisbon Mishneh Torah written by the scribe Solomon ibn Alzuk and completed in 1471-72. The British Library, London, Harley Ms. 5699, fol. 434v. [http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/maimonides/exhibit1.html] |

||

*Golden Haggadah. "The Golden Haggadah, one of the finest surviving Spanish Hebrew manuscripts, was made near Barcelona in Northern Spain. The Haggadah, which literally means ‘narration’, is the service-book used in Jewish households on Passover Eve to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt. The text is preceded by a series of full-page miniatures depicting scenes mainly from the Book of Exodus. These sumptuous illuminations set against gold-tooled backgrounds earned the manuscript its name and were executed in the northern French Gothic style" [http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/hightours/haggadah/ BL] + "The Golden Haggadah is one of the finest of the surviving Haggadah manuscripts from medieval Spain. The Haggadah, which literally means 'narration', is the Hebrew service-book used in Jewish households on Passover Eve at a festive meal to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt. | It is one of the most frequently decorated Jewish books. The fact that it was intended for use at home with its main aim being to educate the young, provides ample scope for artistic creativity. | The Golden Haggadah was probably made near Barcelona in about 1320. In addition to the Haggadah text itself the manuscript contains liturgical Passover poems according to the Spanish rite. The text is preceded by a series of full-page miniatures depicting scenes mainly from the Book of Exodus. These sumptuous illuminations set against gold-tooled backgrounds earned the manuscript its name and were executed by two artists in the northern French Gothic style. | The 17th-century Italian binding has an elaborate border on each cover. Hebrew is written from right to left, so the Golden Haggadah opens from the right. British Library Add. MS 27210 [http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/hagadah/accessible/introduction.html BL Virtual Bk Images Only] |

|||

====IMAGO==== |

====IMAGO==== |

||

| Línea 37: | Línea 36: | ||

File:Printers- Giovanni di Gara, Publisher and proofreader- Israel ben Daniel ha-Zifroni - The Venice Haggadah - Google Art Project.jpg|Hagadá de Venecia, 1609. Impresa por Giovanni di Gara e Israel ben Daniel ha-Zifroni. IM |

File:Printers- Giovanni di Gara, Publisher and proofreader- Israel ben Daniel ha-Zifroni - The Venice Haggadah - Google Art Project.jpg|Hagadá de Venecia, 1609. Impresa por Giovanni di Gara e Israel ben Daniel ha-Zifroni. IM |

||

File:Esther_Megillah_Italy_1616.jpg|Meguilat Ester, Italia, 1616. INUL |

File:Esther_Megillah_Italy_1616.jpg|Meguilat Ester, Italia, 1616. INUL |

||

File:Ms77a-046v.jpg|Mishneh Torah (Maimonides), North-Eastern France, 1296. Kauffman Ms. 77a, fol. 046v.<ref>Another remarkable trait of this manuscript is that it contains many profane illustrations in the margin – in one instance the illustration is even obscene – which bear no relation whatsoever to the text. This cannot be regarded a unique feature of manuscripts produced in the middle of the 13th century: their emergence was closely connected to the spread of Dominican and Franciscan preaching at the time with parables and exempla using motifs from animal fables, bestiaries and – sometimes even becoming completely independent of the text itself. The widespread use of anecdotes in sermons was meant to rekindle flagging interest in theological dogma among believers, and the margin illustrations in manuscripts are to a considerable extent visual manifestations of themes popularized through fabliaux and exempla. Gabrielle Sed-Rajna has shown that most of “the marginal figures have been transferred to this manuscript from a model book used also for several contemporary Latin manuscripts from the same area, executed for the local aristocratic family Bar” – an example of close professional relationship between craftsmen of the Jewish and Christian communities. The popularity of representations of this kind in Christian art in general is attested, for instance, by the fiery diatribe of Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) against non-religious monastic ornamentation. It may be remarked that margin illustrations – including obscene representations – abound in Christian liturgical books while they are rare in secular ones, a strange phenomenon, which Randall is inclined to attribute to an attempt at “provocation by contrast.” Not infrequently it is difficult to decipher the exact symbolic meaning of a given illustration; sometimes this is hardly any longer possible in view of the frequent occurrence of more or less abstruse references to contemporary persons and ideas. There can be no doubt, however, that these margin illustrations were often simply the figments of the artists' imaginations, “diversions which relieved the tedium of daily life.” Thus for instance at the bottom of folio 46 of volume I of our manuscript, the frontispiece of the Book of Adoration, we can see a scene “from the Roman de Renard: the fox, having stolen a goose (or here a cock), is pursued by a woman brandishing a spindle.” In connection with the obscene scene in the upper margin – a man shooting an arrow at the nude hindquarters of a man bending forward – one cannot help but imagine the illuminator who, tired of his monotonous work, suddenly conceives a prank just like an adolescent, in the same way as his modern-day successor, the composer of entries in an encyclopaedia, tired of carding, inserts an entry on a non-existent painter into the serious work of reference, or the lexicographer suddenly gives vent to the accumulated tension of monotony in one of his entries - [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/en/study07.htm].</ref> |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Línea 49: | Línea 47: | ||

[[:en:Category:Judaism in art|Judaism in art]] |

[[:en:Category:Judaism in art|Judaism in art]] |

||

[[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Illuminated_manuscripts_in_Hebrew Heb Ill Mss] |

|||

[[:en:Category:Hebrew_manuscripts,_Wellcome_Collection Heb Mss Wellcome Coll.]] |

|||

[[:en:Category:Illuminated manuscripts in Hebrew|Heb Ill Mss]] |

[[:en:Category:Illuminated manuscripts in Hebrew|Heb Ill Mss]] |

||

| Línea 75: | Línea 77: | ||

[[:en:Category:Images from the Rotschild Haggadah - high resolution|Hagadá Rothschild, It, 1450]] |

[[:en:Category:Images from the Rotschild Haggadah - high resolution|Hagadá Rothschild, It, 1450]] |

||

[[:en:Category:Hebrew_calligraphy Hebrew callygraphy]] |

|||

====LINKS n ARTICLES==== |

====LINKS n ARTICLES==== |

||

[http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0009_0_09500.html JVL Illuminated Hebrew Mss.] |

|||

[http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/index-en.html|Colección David Kaufmann. Mss. miniados hebreos del medioevo . En la Biblioteca de la Academia Húngara de Ciencias.] - [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/index-es.html versión castellana]. - [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study10.htm Hagadá catalana (MS A 422)]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study11.htm ilustrandos]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study12.htm cont.]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study05.htm Mishneh Torah fr (MS A 77)]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study06.htm artistas]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study07.htm profanidad] | [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study08.htm Mahzor (MS A 384)]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study09.htm zodíaco] |

|||

[http://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/digitallibrary/moreshet_bareshet/Pages/damascus.aspx Burgos 1260 (JNL Damascus Keter)] |

|||

[http://www.jtslibrarytreasures.org/ JTS Treasures] |

|||

[http://www.jtsa.edu/prebuilt/prato/index.shtml Prato Haggadah JTS] |

|||

[http://patrimonio-ediciones.com/facsimil/prato-haggadah Prato Haggadah - facsímil] |

|||

[https://jtsa.edu/prebuilt/exhib/prato/index.html Prato Hagadah 2006] |

|||

[http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/index-en.html|Colección David Kaufmann. Mss. miniados hebreos del medioevo . En la Biblioteca de la Academia Húngara de Ciencias.] - [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/index-es.html versión castellana]. - [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/ms422/ms422-coll1.htm folios]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study10.htm Hagadá catalana (MS A 422)]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study11.htm A]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study12.htm B]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study05.htm Mishneh Torah fr (MS A 77)]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study06.htm artistas]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study07.htm profanidad] | [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study08.htm Mahzor (MS A 384)]; [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/study09.htm zodíaco]; ver también: [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/ms77a/ms77a-coll1.htm mishné torá fr 1296 (Ms A 77)] y [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/es/ms384/ms384-coll1.htm Majzor de-sur 1320 (Ms 384)] |

|||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

File:Manuscript_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg|Damascus Keter, Burgos |

File:Manuscript_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg|Damascus Keter, Burgos |

||

File:Kaufmann Haggadah p 014.jpg|The Kaufmann Haggadah (MS Kaufmann A 422) was produced in 14th century Catalonia. It contains the prayers, poems and narrative texts to be recited on the eve of the festival of the Jewish Easter, Pesach, the Feast of the Passover. |

File:Kaufmann Haggadah p 014.jpg|The Kaufmann Haggadah (MS Kaufmann A 422) was produced in 14th century Catalonia. It contains the prayers, poems and narrative texts to be recited on the eve of the festival of the Jewish Easter, Pesach, the Feast of the Passover. fol. 13r |

||

File:Illustration-haggadah-pesach.jpg |

File:Illustration-haggadah-pesach.jpg |

||

File:Illustration-haggadah-exodus.jpg |

File:Illustration-haggadah-exodus.jpg |

||

| Línea 90: | Línea 103: | ||

File:Illustration-burning-bush-with-christ.gif |

File:Illustration-burning-bush-with-christ.gif |

||

File:Ligature-Alef-Lamed.JPG |

File:Ligature-Alef-Lamed.JPG |

||

File:Illustration-machzor-hunting-scene.gif|Majzor (tripartito) 1320 |

|||

File:Ms77a-046v.jpg|Mishneh Torah (Maimonides), North-Eastern France, 1296. Kauffman Ms. 77a, fol. 046v.<ref>Another remarkable trait of this manuscript is that it contains many profane illustrations in the margin – in one instance the illustration is even obscene – which bear no relation whatsoever to the text. This cannot be regarded a unique feature of manuscripts produced in the middle of the 13th century: their emergence was closely connected to the spread of Dominican and Franciscan preaching at the time with parables and exempla using motifs from animal fables, bestiaries and – sometimes even becoming completely independent of the text itself. The widespread use of anecdotes in sermons was meant to rekindle flagging interest in theological dogma among believers, and the margin illustrations in manuscripts are to a considerable extent visual manifestations of themes popularized through fabliaux and exempla. Gabrielle Sed-Rajna has shown that most of “the marginal figures have been transferred to this manuscript from a model book used also for several contemporary Latin manuscripts from the same area, executed for the local aristocratic family Bar” – an example of close professional relationship between craftsmen of the Jewish and Christian communities. The popularity of representations of this kind in Christian art in general is attested, for instance, by the fiery diatribe of Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) against non-religious monastic ornamentation. It may be remarked that margin illustrations – including obscene representations – abound in Christian liturgical books while they are rare in secular ones, a strange phenomenon, which Randall is inclined to attribute to an attempt at “provocation by contrast.” Not infrequently it is difficult to decipher the exact symbolic meaning of a given illustration; sometimes this is hardly any longer possible in view of the frequent occurrence of more or less abstruse references to contemporary persons and ideas. There can be no doubt, however, that these margin illustrations were often simply the figments of the artists' imaginations, “diversions which relieved the tedium of daily life.” Thus for instance at the bottom of folio 46 of volume I of our manuscript, the frontispiece of the Book of Adoration, we can see a scene “from the Roman de Renard: the fox, having stolen a goose (or here a cock), is pursued by a woman brandishing a spindle.” In connection with the obscene scene in the upper margin – a man shooting an arrow at the nude hindquarters of a man bending forward – one cannot help but imagine the illuminator who, tired of his monotonous work, suddenly conceives a prank just like an adolescent, in the same way as his modern-day successor, the composer of entries in an encyclopaedia, tired of carding, inserts an entry on a non-existent painter into the serious work of reference, or the lexicographer suddenly gives vent to the accumulated tension of monotony in one of his entries - [http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/en/study07.htm].</ref> |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Línea 95: | Línea 110: | ||

*[http://www.imj.org.il/imagine/galleries/judaicaE.asp IM: Judaica] |

*[http://www.imj.org.il/imagine/galleries/judaicaE.asp IM: Judaica] |

||

*[http://www.imj.org.il/imagine/galleries/viewGalleryE.asp?case=26 IM: ILL MSS] |

*[http://www.imj.org.il/imagine/galleries/viewGalleryE.asp?case=26 IM: ILL MSS] |

||

*[https://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/children/exhibit1.html Hagadot manuscritas] |

|||

*[http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/maimonides/introduction.html Expo Maimónides at Yale] |

*[http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/maimonides/introduction.html Expo Maimónides at Yale] |

||

*[http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/maimonides/exhibit1.html Maimónides Ill. Mss. at Yale] |

*[http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/maimonides/exhibit1.html Maimónides Ill. Mss. at Yale] |

||

*[https://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/children/exhibit2.html hagadot impresas] |

|||

* [http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/collection/incunabula.php libros impresos siglo XV] |

* [http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/collection/incunabula.php libros impresos siglo XV] |

||

* [http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/collection/16imprints.php idem siglo XVI] |

* [http://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/collection/16imprints.php idem siglo XVI] |

||

*[https://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/children/exhibit4.html hagadot modernas] |

|||

*[https://www.library.yale.edu/judaica/site/exhibits/children/exhibit3.html hagadot IL] |

|||

McBee |

McBee |

||

[http://richardmcbee.com/images/pdfs/Jewish_Art_Primer_Complete.pdf jewish art definition] |

|||

[http://richardmcbee.com/writings/jewish-art-before-1800/item/the-sarajevo-haggadah-the-choice-of-images sarajevo] |

|||

[http://richardmcbee.com/writings/jewish-art-before-1800/item/rylands-haggadah-part-i rylands 1] |

|||

[http://richardmcbee.com/writings/jewish-art-before-1800/item/rylands-haggadah-part-ii rylands 2] |

|||

[http://richardmcbee.com/writings/jewish-art-before-1800/item/rylands-haggadah-medieval-jewish-art-in-context rylands in context] |

|||

[http://richardmcbee.com/writings/jewish-art-before-1800/item/synagogues-in-spain ES synagogues] |

|||

[https://www.pinterest.com/mothemelusine/medieval-and-renaissance-jewish-illuminated-manusc/ Heb Mss S Collection Pins] |

|||

[https://www.pinterest.com/nenarok/hebrew-manuscripts/ Heb Mss Russian Collection Pins] |

|||

[https://www.pinterest.com/der4321/art-et-monde-juif/ Superfine Judaica French Collection Pins] |

|||

[https://www.pinterest.com/mscogsworthy/history-jewish-spain/ Sefarad Pins] |

|||

[https://www.pinterest.com/alisonshearman/haggadah-hagadah/ Haggadah Pins] |

|||

[https://www.pinterest.com/igoldfarb/judaica/ Judaica] |

|||

BL Virtual Books : [http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/hagadah/accessible/introduction.html Accesible Golden Haggadah] - [http://www.bl.uk/turning-the-pages/?id=47111807-4e9a-43de-be65-96f49c3d623c&type=book Golden Haggadah] - |

|||

[http://www.bl.uk/turning-the-pages/?id=4145201d-ee22-4382-9ae8-2c78d9138444&type=book Lisbon Bible] - [http://www.bl.uk/turning-the-pages/?id=47111807-4e9a-43de-be65-96f49c3d623c&type=book Vesalius] |

|||

====Prato Hagadá==== |

|||

[http://www.jtslibrarytreasures.org/ JTS Treasures] |

|||

[http://patrimonio-ediciones.com/facsimil/prato-haggadah facsimil eds] |

|||

[http://www.jtsa.edu/prebuilt/prato/index.shtml historia] |

|||

[https://jtsa.edu/prebuilt/exhib/prato/index.html expo con datos] |

|||

====JWS MS==== |

|||

[http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0009_0_09500.html JWS MSS en JVL] |

|||

[http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/en/study02.htm Hungarian Academy of Sciences: Kaufmann Collection] |

|||

[http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=19108&CollID=27&NStart=27210 BL: Golden Haggadah Entry] |

|||

====[http://www.schechter.edu/facultyForum.aspx?ID=120 Schechter Institute on Akedah]==== |

|||

Prior to the 1930`s, most scholars were convinced that ancient Jewry produced no art. As a result, the discovery in 1932 of the biblical wall-paintings decorating the third century synagogue of Dura Europos,Syria stunned the academic world. In these earliest extant examples of Jewish art (antedating comparable Christian art by two centuries) the community expresses its acceptance of pious rabbinic midrashim. Center stage above the Torah ark, a naively drawn Abraham stands firm before the altar, knife raised, his back to the viewer. Dura Europos Synagogue, Akedah (detail), 244 C.E. |

|||

he saving ram is tethered behind Abraham awaiting its theological moment. Tiny Isaac is impaled upon a monumental altar (see the Midrash in Targum Yonatan, below). He too looks away from us, as does Sarah (rarely represented in akedah scenes) in the doorway of her tent, the highest and most distant point of the scene. They are all focused on the hand of God, "the Place from afar" at Moriah (v.3), identified in late biblical times as the site of the once and forever restored Temple of Jerusalem. 170 years after its destruction, the Temple and its implements are visually restored at the center and left of this scene, together with the akedah, the symbols of Diaspora hope for national and religious restoration. Dura Europos Synagogue, Akedah |

|||

Just three years prior to the discovery of Dura, a stunning mosaic floor of a 6th century synagogue had been uncovered at Kibbutz Bet Alpha., the earliest akedah to be found in Israel. The naive style of the mosaic displays Jewish, pagan and possibly Christian elements. On entering the synagogue, the worshiper first encountered the akedah, a focal narrative of Jewish tradition. The worshiper next saw a zodiac, centered on the sun god Helios and his chariot. Is this a synagogue? It is likely that these pagan symbols were interpreted as representing the ritual calendar of the congregation - but, it is also evidence of a Judaism culturally alive to the imagery of the Greco-Roman Byzantine heritage. Finally, in the third section, closest to the holy ark, the worshiper saw (as in Dura) the doors, menorah and ritual tools of the restoredTemple. Left: Bet Alpha Synagogue, Entire Floor |

|||

Above right: detail, Bet Alpha Synagogue, Akedah, 6th century: The playful color patterns and paper-doll character of the figures belie the theological intensity of the akedah scene. The two servants stand at the left, together with the ass (v. 5). At the center point, the ram hangs from a bush, rather than being caught in the thicket, as recounted in the Bible (v. 13). Above, a haloed hand of the angel "calls out": Do not raise [your hand] (v. 11 – 12). On the right, the child Isaac is held aloft between Abraham and the burning altar (v. 10). The artists altered the sequence of the story by placing the ram at center stage. Thus the mosaic seems to focus on God’s compassionate substitution of Isaac by the ram, rather than on Abraham’s extraordinary act of faith. It has been suggested that the hanging ram is based on Christian iconography, connecting Isaac, the ram and Jesus as parallel sacrifices. But just as in the use of the pagan zodiac, the borrowing of this model does not imply a heterodox interpretation, but rather cultural contact. |

|||

In 1947, Mordecai Ardon paints the worst scenario. Isaac lies dead at Sarah’s feet, his mother a large, grotesque weeping figure, screams the call of the shofar. Parallel and opposite the fallen Isaac, a fallen ladder of Jewish continuity conveys two dead ends: Jacob’s ladder, that will not be, and the train tracks to Auschwitz. The faceless mother and child echo the universal pieta motif, the mother holding her deceased child, whether in antiquity or in our times. M. Ardon, Sarah, 1947 |

|||

==A traducir e incluir== |

|||

[http://www.cafetorah.com/portal/Curso-de-Hebraico fuente fechada 20.8.2011, 6.7.15] |

|||

O idioma hebraico (עברית, ivrit) é uma língua semítica pertencente à família das línguas afro-asiáticas, o termo semítico determina que bem como o árabe e o persa, sua orígem é um tanto desconhecida. As primeiras bases da Bíblia, a Torá, que os judeus ortodoxos consideram ter sido escrita na época de Moisés, cerca de 3.300 anos atrás, foi redigida no hebraico chamado de "Hebraico Clássico". |

|||

Embora hoje em dia seja uma escrita foneticamente impronunciável, portanto indecifrável, devido à não-existência de vogais no alfabeto hebraico clássico, os judeus têm-na sempre chamado de לשון הקודש, Lashon haKodesh ("A Língua Sagrada") já que muitos acreditam ter sido escolhida para transmitir a mensagem de Deus à humanidade. |

|||

Após a primeira destruição de Jerusalém pelos babilônios em 586 a.C., com o retorno dos judeus para a Terra de Israel, o hebraico clássico foi substituído no uso diário pelo aramaico, tornando-se primariamente uma língua regional, tanto usada na liturgia, no estudo do Mishná (parte do Talmude), bem como também no comércio. Sendo que nos dias de Yeshua(Jesus), este idioma clássico ainda era falados sacerdores, levitas, saduceus e os fariseus doutores da lei, mas o povo em geral utilizava o Aramaico como idioma no dia a dia. |

|||

Após a destruição de Jerusalém no ano 70 DC, os judeus foram aos poucos expulsos da Terra de Israel, os que ficaram sofreram influencia dos muitos povos que dominaram na região e o Hebraico deixou de ser utilizado como idioma nacional, passando ser utilizado apenas em liturgias religiosas. |

|||

O hebraico renasceu como língua falada durante o final do século XIX e começo do século XX como o hebraico moderno, adotando alguns elementos dos idiomas árabe, ladino, iídiche, e outras línguas que acompanharam a Diáspora Judaica como língua falada pela maioria dos habitantes do Estado de Israel, do qual é a língua oficial primária (o árabe também tem status de língua oficial) |

|||

1) Hebreo clásico. http://www.cafetorah.com/portal/Hebraico-Biblico-Hebraico-Classico |

|||

Hebraico bíblico, também chamado de hebraico clássico, é a forma arcaica da língua hebraica, uma língua semita falada na área conhecida como Canaã, entre o Rio Jordão e o Mar Mediterrâneo. Hebraico bíblico é conhecido por volta do século 10 AC, e persistiu durante todo o período do Segundo Templo (que termina em 70 dC). O Hebraico bíblico tornou-se eventualmente hebraico Mishnaico que foi usado até o segundo século EC. |

|||

O Hebraico bíblico é mais bem utilizado na Bíblia Hebraica, a Bíblia é um documento que reflete vários estágios da língua hebraica em sua forma consonantal, bem como um sistema vocálico que foi adicionado mais tarde, na Idade Média. Há também algumas evidências de variação dialética regional, incluindo as diferenças entre o hebraico bíblico falado no Reino do Norte de Israel e no Reino do sul, o Reino de Judá. |

|||

Hebraico Bíblico foi escrito com um número de diferentes sistemas de escrita. Segundo os historiadores, os hebreus adotaram a escrita fenícia em torno do século 12 AC, que teria evoluido como a escrita Paleo-Hebraico. Esta foi mantida pelos samaritanos, que usam o manuscrito Samaritano desde então até os dias de hoje. No entanto, o roteiro aramaico gradualmente deslocou o roteiro Paleo-Hebrew para os judeus, e tornou-se a fonte para o alfabeto hebraico moderno. Todas esses escritas faltavam letras para representar todos os sons do hebraico bíblico, ainda que estes sons são refletidos mas trancrições em grego e latim da mesma época. Estes escritas originalmente utilizadas apenas como consoantes, mas certas letras, conhecidas como matrizes de leituras, tornaram-se cada vez mais usadas para marcar as vogais. Na Idade Média, vários sistemas de sinais diacríticos foram desenvolvidos para marcar as vogais em manuscritos hebraicos, dos quais somente o sistema Tiberiano ainda está em ampla utilização. |

|||

O Hebraico Bíblico possuía uma série de "enfátizações" nas consoantes cuja articulação precisa é disputada, provavelmente palatais, guturais ou falangiais. O Hebraico Bíblico anteriormente possuía três consoantes que não têm suas próprias formas no sistema de escrita, mas com o tempo eles se fundiu com outras consoantes. As consoantes se desenvolveram em alofones fricativos sob a influência do aramaico, e esses sons se tornaram uma marginal fonêmica. Os fonemas da faringe e da glote sofreu enfraquecimento em alguns dialetos regionais, como refletido na moderna tradição de leitura do Hebraico Samaritano. O sistema de vogal do Hebraico Bíblico mudou drasticamente ao longo do tempo e é refletida de forma diferente nas transcrições do grego antigo e latim, sistemas de vocalização medieval, moderna e as tradições de leitura. |

|||

Hebraico Bíblico tinha uma morfologia típica semita, colocando raízes triconsonantal em padrões para formar palavras. Hebraico bíblico distinguia dois gêneros (masculino, feminino), três números (plural, singular e extraordinariamente dual). Verbos foram marcados para voz e expressão, e teve duas conjugações que pode ter indicado aspecto e / ou tenso (a questão de debate). O tempo ou aspecto dos verbos também foi influenciado pela conjugação, na construção VAV chamados consecutivos. Ordem das palavras padrão era verbo-sujeito-objeto, e os verbos flexionados para o número, gênero e pessoa do seu objecto. Sufixos pronominais podem ser anexado aos verbos (para indicar objeto) ou substantivos (para indicar posse), e substantivos tinham formas de construção especial para uso em construções possessivas. |

|||

2) Hebreo mishnáico. http://www.cafetorah.com/portal/Hebraico-Mishnaico |

|||

O termo Hebraico Mishnaico refere-se à dialetos do hebraico que são encontrados no Talmud, exceto citações da Bíblia hebraica. Os dialetos podem ainda ser sub-dividido em Hebraico Mishnaic (também chamado de Hebraico Tanaitico, Hebraico da Lei Rabínica, ou Hebraico Mishnaico I), que era uma língua falada, e hebraico Amoraico (também chamado Hebraico Rabínico Tardio ou Hebraico Mishnaico II), que foi uma língua somente literária. |

|||

A língua hebraica Mishnaica ou o início de idioma hebraico rabínico é um descendente direto do antigo hebraico bíblico como preservado pelos judeus depois do cativeiro babilônico, e definitivamente gravados por sábios judeus, por escrito, os documentos da Mishnah e outros contemporâneos. Não foram utilizados pelos samaritanos, que preservaram seu próprio dialeto, o Hebraico Samaritano. |

|||

A forma de transição da língua ocorre em outras obras na literatura Tanaitica datada do início do século, com a conclusão da Mishná. Estes incluem o Midrashim Halachic (Sifra, Sifre, Mechilta etc) e a coleção expandida do material do Mishnah relacionado com o conhecido como o תוספתא Tosefta. O Talmud contém trechos destas obras, bem como material Tanaitico ainda não atestado em outro lugar; o termo genérico para essas passagens é Baraitot. O dialeto de todas essas obras é muito semelhante ao Hebraico Mishnaico. |

|||

Este dialeto é surgiu principalmente a partir do 2º ao 4º século DC, correspondente ao Período Romano após a destruição do Templo em Jerusalém e foi representado pela maior parte no Mishnah e na Tosefta dentro do Talmud e pelos Manuscritos do Mar Morto, são considerada também as cartas de Bar Kokhba e o Rolo de Cobre. Também chamado de Hebraico Tanaitico ou Hebraico Rabínico Precoce. |

|||

A primeira seção do Talmud é a משנה Mishnah que foi publicado por volta de 200 DC e foi escrito no dialeto Mishnaico anterior. O dialeto também é encontrado em certos trechos dos manuscritos do Mar Morto. |

|||

Cerca de um século após a publicação da Mishná, o Hebraico Mishnaico começou a cair em desuso como língua falada. No período posterior do Talmud, a Guemará babilônica גמרא, comentários publicados cerca de 500 DC, geralmente na Mishná e Baraitot em Aramaico. (Uma versão anterior do Gemara foi publicada entre 350-400 AD.) No entanto, o hebraico sobreviveu como língua litúrgica e literária, na forma do hebraico depois como Amoraico, que às vezes pode ser visto no texto da Gemara. |

|||

O Hebraico Mishnaic se desenvolveu sob a profunda influência do aramaico falado em todas as esferas da linguagem, incluindo fonologia, morfologia, sintaxe e vocabulário. |

|||

Fonética |

|||

Muitos dos traços característicos da pronúncia hebraica pode muito bem ter sido encontrado já no período do hebraico bíblico tardio. Uma característica notável que a distingue de hebraico bíblico do período clássico é acentuação pós-vocálica pára (b, g, d, p, t, k), que tem em comum com o aramaico. |

|||

Uma característica nova é que a letra M final é muitas vezes substituída por N final na Mishna (ver Bava Kama 1:4, "מועדין"), mas apenas em conotações fonéticas. Talvez a consoante final nasal nestes morfemas não éra pronunciada, e ao invéz disso, a vogal anterior à ela era nasalizadas. Alternativamente, os morfemas podem ter mudado sob a influência do aramaico. |

|||

Além disso, alguns manuscritos sobreviventes da Mishná confundem as consoantes guturais, especialmente (א) (uma parada glotal) e 'ayin (ע) (a fricativa faríngea, gutural). Que poderia ser um sinal de que eles foram pronunciados da mesma forma no Hebraico Mishnaico. Bem como nos dias de hoje são pouco difenciados no Hebraico Moderno. |

|||

3) Hebreo medieval. http://www.cafetorah.com/portal/Hebraico-Medieval |

|||

O Hebraico Medieval tem muitas características que o distinguem das formas mais antigas do hebraico. A Gramática, sintaxe, estrutura de sentença, e também incluem uma grande variedade de novos itens lexicais, que são geralmente baseados em formas mais antigas. |

|||

Na idade de Ouro da Cultura Judaica na Espanha um importante trabalho foi feito por gramáticos para explicar a gramática e o vocabulário do hebraico bíblico, muito disso foi baseado no trabalho dos gramáticos de árabe clássico. Gramáticos hebreus importantes foram Judah ben David Hayyuj e Jonas ibn Janah. Uma grande parte da poesia foi escrita, por poetas como Dunash Ben Labrat, Solomon ibn Gabirol, Judah ha-Levi, haKohen David e os dois Ezras Ibn, em uma "purificação" em hebraico com base no trabalho desses gramáticos, e em árabe metros quantitativos (ver piyyut). Este hebraico literário foi usado mais tarde pelo poetas italianos judeus. |

|||

A necessidade de expressar conceitos científicos e filosóficos de grego clássico e o Hebraico Medieval motivado pelo Árabe Medieval influenciou a terminologia e a gramática a partir desses outros idiomas, ou a termos de moeda equivalente a partir de raízes existentes no hebraico, dando origem a um estilo distinto do hebraico filosófico. Muitos paralelos diretos em árabe medieval. A família Tibbon Ibn e, especialmente, Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon foram pessoalmente responsáveis pela criação de grande parte desta forma de hebraico, que empregaram em suas traduções de materiais científicos do árabe. Naquele tempo, a original judaica de obras filosóficas eram geralmente escritas em árabe, mas como o passar do tempo, esta forma de hebraico era usada para muitas composições originais também. |

|||

Outra influência importante foi Maimonides, que desenvolveu um estilo simples, baseado no Hebraico Mishnaico para usar em seu código de leis, o Mishneh Torá. Literatura rabínica posterior que foi escrita em uma mistura entre este estilo e o hebraico rabínico Aramaizado do Talmud. |

|||

No final do século XII e início do século XIII o centro cultural de Judeus no Mediterrâneo foi transferido de um contexto islâmico para terras cristãs. O hebraico escrito usado no Norte da Espanha, Provença (um termo para todo o sul da França) e da Itália era cada vez mais influenciado pela América, particularmente nos escritos filosóficos, e também por diferentes vernáculos (provençal, italiano, etc.) Na Itália, testemunhamos o surgimento de um novo gênero, léxicos filosóficos Italiano-Hebraico. O italiano desses léxicos era geralmente escrito em caracteres hebraicos e são uma fonte útil para o conhecimento da filosofia escolástica entre os judeus. Um dos primeiros léxicos que foi por Moisés b. Shlomo de Salerno, que morreu no final do século XIII. Ele foi feito para esclarecer os termos que aparecem em seu comentário sobre o Guia dos Perplexos de Maimônides. O glossário de Moisés de Salerno foi editado por Giuseppe Sermoneta em 1969. Há também glossários associados aos sábios judeus que fizeram amizade com Pico della Mirandola. Moisés de Salerno também fez um comentário sobre o Guia também contém traduções italianas de termos técnicos, o que traz sistema islâmico de influência do Guia filosófico em confronto com a escolástica do século XIII italiano. |

|||

O Hebraico também foi usado como língua de comunicação entre os judeus de diferentes países, particularmente para o propósito do comércio internacional. |

|||

Mencionam-se ainda cartas preservadas no geniza Cairo, que mostram que o hebraico e o árabe influenciaram os judeus do Egito medieval. Os termos árabes e sintaxe que aparecem nas cartas constituem uma importante fonte para a documentação da língua falada em árabe medieval, desde que os judeus em terras islâmicas tendem a usar o árabe coloquial, por escrito, em vez de árabe clássico, que é o árabe que aparece em medievais. |

|||

==Trabajados== |

==Trabajados== |

||

| Línea 138: | Línea 264: | ||

* [[Mano de Dios]] |

* [[Mano de Dios]] |

||

* [[Moisés]] |

* [[Moisés]] |

||

* [[Sanctasanctórum |

* [[Sanctasanctórum]] |

||

==Trabajados eventualmente== |

==Trabajados eventualmente== |

||

| Línea 246: | Línea 372: | ||

File:A. Salzmann - Fragments Juda ï que et Romain.jpg|Fragmentos arqueológicos judaico y romano. Fotografiados por [[Auguste Salzmann]] en 1853. |

File:A. Salzmann - Fragments Juda ï que et Romain.jpg|Fragmentos arqueológicos judaico y romano. Fotografiados por [[Auguste Salzmann]] en 1853. |

||

[[Archivo:Silver shekel - First Jewish Revolt, 2nd year.jpg|200px|thumb|Antiguo [[shéquel]] de plata de [[Israel]], con [[Kidush|cáliz de kidush]] y [[Punica granatum|tres granadas]] simbólicas de Judea, Samaria y Galilea, forjado en el segundo año de la [[Primera Guerra Judeo-Romana|Primera Guerra Judía contra Roma]], 66-73 E.C. |

[[Archivo:Silver shekel - First Jewish Revolt, 2nd year.jpg|200px|thumb|Antiguo [[shéquel]] de plata de [[Israel]], con [[Kidush|cáliz de kidush]] y [[Punica granatum|tres granadas]] simbólicas de Judea, Samaria y Galilea, forjado en el segundo año de la [[Primera Guerra Judeo-Romana|Primera Guerra Judía contra Roma]], 66-73 E.C. |

||

File: |

File:David Roberts - The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans Under the Command of Titus, A.D. 70.jpg|Sitio y destrucción de Jerusalén por los romanos, 70 EC (Roberts, 1850) |

||

File:Sack_of_jerusalem.JPG|Expolios de Jerusalén, 70 EC |

File:Sack_of_jerusalem.JPG|Expolios de Jerusalén, 70 EC |

||

| Línea 257: | Línea 383: | ||

File:Roman. Mosaic of Menorah with Lulav and Ethrog, 6th century C.E.jpg|Mosaico con [[Menorá]], lulav y etróg'', siglo VI. |

File:Roman. Mosaic of Menorah with Lulav and Ethrog, 6th century C.E.jpg|Mosaico con [[Menorá]], lulav y etróg'', siglo VI. |

||

File: |

File:Reception of Jews in Poland 1096.jpg|Llegada de los judíos a Polonia, 1096 (Jan Matejko, s. XIX). |

||

File:1099jerusalem.jpg|Los cruzados capturan Jerusalén, 1099 |

File:1099jerusalem.jpg|Los cruzados capturan Jerusalén, 1099 |

||

| Línea 286: | Línea 412: | ||

[https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%91%D7%A5:Ark_Jerusalem.jpg Augusta Victoria] |

[https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%91%D7%A5:Ark_Jerusalem.jpg Augusta Victoria] |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

|Réplica del Arca de la Alianza |

|||

File:Figures_060_The_erection_of_the_Tabernacle_and_the_Sacred_vessels_(right_plate).jpg|The Erection of the Tabernacle and the Sacred vessels (right plate); as in Exodus 40:17-19: "And it came to pass in the first month in the second year, on the first day of the month, that the tabernacle was reared up. And Moses reared up the tabernacle, and fastened his sockets, and set up the boards thereof, and put in the bars thereof, and reared up his pillars. And he spread abroad the tent over the tabernacle, and put the covering of the tent above upon it; as the Lord commanded Moses."; illustration from the 1728 Figures de la Bible; illustrated by Gerard Hoet (1648–1733) and others, and published by P. de Hondt in The Hague; University of Oklahoma Libraries |

File:Figures_060_The_erection_of_the_Tabernacle_and_the_Sacred_vessels_(right_plate).jpg|The Erection of the Tabernacle and the Sacred vessels (right plate); as in Exodus 40:17-19: "And it came to pass in the first month in the second year, on the first day of the month, that the tabernacle was reared up. And Moses reared up the tabernacle, and fastened his sockets, and set up the boards thereof, and put in the bars thereof, and reared up his pillars. And he spread abroad the tent over the tabernacle, and put the covering of the tent above upon it; as the Lord commanded Moses."; illustration from the 1728 Figures de la Bible; illustrated by Gerard Hoet (1648–1733) and others, and published by P. de Hondt in The Hague; University of Oklahoma Libraries |

||

File:Cathédrale d'Auch 20.jpg|Transport of the Ark, Auch Cathedral, France |

File:Cathédrale d'Auch 20.jpg|Transport of the Ark, Auch Cathedral, France |

||

| Línea 306: | Línea 432: | ||

File:Bikur_Cholim_Hospital_04.jpg|Ze'ev Raban |

File:Bikur_Cholim_Hospital_04.jpg|Ze'ev Raban |

||

File:Russian_-_Bowl_with_Judah_and_Lion_Surrounded_by_Scened_from_the_Book_of_Esther_-_Walters_4446.jpg|Judá y el león; escenas de la historia de Ester. Moscú, 1690 |

File:Russian_-_Bowl_with_Judah_and_Lion_Surrounded_by_Scened_from_the_Book_of_Esther_-_Walters_4446.jpg|Judá y el león; escenas de la historia de Ester. Moscú, 1690 |

||

File: |

File:Tombstone of Hendel Bassevi (née Geronim) at the Old Jewish Cemetery of Prague.jpg|[[León de Judá]] |

||

File:Kirkut Skwierzyna 8325.JPG|Cementerio judío de Skwierzyna, Polonia |

File:Kirkut Skwierzyna 8325.JPG|Cementerio judío de Skwierzyna, Polonia |

||

File:Radom Jewish Cemetery - matzeva1.jpg|Cementerio judío de Radom |

File:Radom Jewish Cemetery - matzeva1.jpg|Cementerio judío de Radom |

||

| Línea 603: | Línea 729: | ||

* [http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Holocaust holocaust] |

* [http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Holocaust holocaust] |

||

* [http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Land_of_Israel land of il]</small> |

* [http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Land_of_Israel land of il]</small> |

||

== Golden Haggadah DATA == |

|||

Golden Haggadah, Northern Spain, probably Barcelona, c.1320 |

|||

British Library Add. MS. 27210 |

|||

Golden Haggadah |

|||

The extravagant use of gold-leaf in the backgrounds of its 56 miniature paintings earned this magnificent manuscript its name: the 'Golden Haggadah'. It was made around 1320, in or near Barcelona, for the use of a wealthy Jewish family. The holy text is written on vellum pages in Hebrew script, reading from right to left. Its stunning miniatures illustrate stories from the biblical books of 'Genesis' and 'Exodus' and scenes of Jewish ritual. |

|||

What does this page show? |

|||

Anticlockwise from top right: Adam naming the animals, the Creation of Adam and Eve, the Temptation, Cain and Abel offering a sacrifice, Cain slaying Abel, and lastly Noah, his wife and sons coming out of the ark. God's image is forbidden in Jewish religious contexts, and is totally absent in all the miniatures here. Instead, angels are seen intervening at critical moments. |

|||

What is a haggadah? |

|||

A haggadah is a collection of Jewish prayers and readings written to accompany the Passover 'seder', a ritual meal eaten on the eve of the Passover festival. The ritual meal was formalised during the 2nd century, after the example of the Greek 'symposium', in which philosophical debate was fortified by food and wine. |

|||

The literal meaning of the Hebrew word 'haggadah' is a 'narration' or 'telling'. It refers to a command in the biblical book of 'Exodus', requiring Jews to "tell your son on that day: it is because of that which the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt". |

|||

Perhaps because it was mainly intended for use at home, and its purpose was educational, Jewish scribes and artists felt completely free to illustrate the Haggadah. Indeed it was traditionally the most lavishly decorated of all Jewish sacred writings, giving well-to-do Jews of the middle ages a chance to demonstrate their wealth and good taste as well as their piety. The man for whom the 'Golden Haggadah' was made must have been rich indeed. |

|||

What is Passover? |

|||

Passover commemorates one of the most important events in the story of the Jewish people. Like Christianity and Islam, Judaism traces its origins back to Abraham. He was leader of the Israelites, a group of nomadic tribes in the Middle East some 4,000 years ago. Abraham established a religion that distinguished itself from other local beliefs by having only one, all-powerful God. According to a Covenant made between them, the Jews would keep God's laws, and in return they would be protected as chosen people. |

|||

The Israelites were captured and taken as slaves to Egypt, where they suffered much hardship. Eventually, a prophet called Moses delivered the Jews from their captivity with the help of several miraculous events intended to intimidate the Egyptian authorities. The last of these was the sudden death of the eldest son in every family. Jewish households were spared by smearing lambs' blood above their doors - a sign telling the 'angel of death' to pass over. |

|||

Why was a Jewish manuscript made in Spain? |

|||

The wandering tribes of Israel finally settled in the 'promised land' after their delivery from captivity in Egypt. But the twin kingdoms of Israel and Judah were to fall to the Assyrians and Babylonians. Then, in 63 BC, the region came under the governance of the Roman Empire. In 70 AD, the Roman army destroyed the Second Jewish Temple and sacked Jerusalem; in 135 AD they crushed a Judaean uprising. As a result of this many Jews went into exile. |

|||

Some migrated across north Africa to Spain. For many centuries, these 'Sephardic' Jews lived peacefully and productively under both Christian and Islamic rulers. The Jewish community in Barcelona had been established since Roman times and was one of the most affluent in Spain by the time the 'Golden Haggadah' was produced. |

|||

Jews acted as advisers, physicians and financiers to the Counts of Barcelona, who provided economic and social protection. They grew attuned to the tastes of the court and began commissioning manuscripts decorated in Christian style. Though the scribe who wrote its Hebrew text would have been a Jew, the illuminators of the 'Golden Haggadah' are likely to have been Christian artists, instructed in details of Judaic symbolism by the scribe or patron. |

|||

Who made the Golden Haggadah? |

|||

The illumination of the manuscript - its paintings and decoration - was carried out by two artists. Though their names are unknown, the similarity of their styles implies they both worked in the same studio in the Barcelona region. The gothic style of northern French painting was a strong influence on Spanish illuminators, and these two were no exceptions. |

|||

There is also Italian influence to be seen in the rendering of the background architecture. Differences between the two artists may be attributed to their individual talents and training. The painter of the scenes shown here tends towards stocky figures with rather exaggerated facial expressions. The second artist has a greater sense of refinement and achieves a better sense of space. |

|||

How did the 'Golden Haggadah' come to the British Library? |

|||

Islamic rule in Spain came to an end in 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella (the Catholic Monarchs) defeated the Muslim army at Granada and restored the whole of Spain to Christianity. Months later the entire Jewish population was expelled. The manuscript found its way to Italy and passed through various hands, serving as a wedding present at one stage. In 1865, the British Library (then the British Museum Library) bought it as part of the collection of Hebrew poet and bibliophile Giuseppe (or Joseph) Almanzi. |

|||

[http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/sacredtexts/golden.html BL] |

|||

− |

|||

== Arte y escritura hebrea == |

|||

− |

|||

<gallery widths=200 heights=200> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Kohenbreastplate.jpg|''Jóshen'' o Pectoral del [[Anexo:Sumos Sacerdotes de Israel|Sumo Sacerdote]] de los [[hebreos]], con una docena de piedras preciosas simbolizando las [[Doce Tribus de Israel]].<ref>[http://legacy.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=%C3%89xodo28&version=RVR1960 Éxodo 28]; ''Encyclopedia Judaica'', Nueva York, 1905-6.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Menorah engraving, Great Mosque of Gaza.jpg|Diseño del relieve hallado en la [[Gran Mezquita de Gaza]], con inscripciones en hebreo y griego. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Leningrad Codex Carpet page e.jpg|[[Códice de Leningrado]], 1008 E.C. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Worms festival prayerbook.jpg|[[Arte asquenazí]]. ''Libro de oraciones de Worms'', c. 1285-90. Biblioteca Nacional, Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Birdhea5.jpg|Los hebreos recolectan el maná y reciben la [[Torá|Ley]]. ''[[Hagadá]] de los Pajaritos'' (Pésaj), c. 1300.<ref>En este manuscrito preservado en el [[Museo de Israel]] en Jerusalén, las figuras con cabeza de ave también bendicen el vino, se lavan las manos antes de comer vegetales y recitan poemas litúrgicos llamados en hebreo ''paytanim'' (Elie Kedourie, ''Le monde du judaïsme'', Londres y París: Thames & Hudson, 2003, pp. 117-118, 259). Para una posible interpretación de la relación entre texto e imagen en este manuscrito, véase Marc Michael Epstein, ''The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative & Religious Imagination'', New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011; y Richard McBee, "[http://www.jewishpress.com/sections/arts/birds-head-haggadah-revealed-the-medieval-haggadah-art-narrative-religious-imagination/2012/03/29/0/ Bird’s Head Haggadah Revealed]", ''The Jewish Press'', 29 de marzo de 2012 (consultado 21 de noviembre de 2014).</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Barcelona Haggadah 30v.jpg|[[Arte sefardí]]. [[Hagadá|Hagadá Barcelona]],<ref>Manuscrito hebreo-catalán presevado y exhibido en la British Library de Londres (BL Add MS 14761).</ref> manuscrito hebreo, 1350, fol. 30v: "Esclavos fuimos de Faraón en Egipto." |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Ha Lahma Ania.jpg|[[Hagadá|Hagadá Barcelona]], 1350: "Ha-Lajmanía" |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Barcelona Haggadah 42v.l.jpg|[[Hagadá|Hagadá Barcelona]], 1350, fol. 42v |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Kaufmann Haggadah p 014.jpg|Texto hebreo con caracteres típicamente sefarditas, Hagadá de Cataluña, siglo XIV. Colección Kaufmann |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Illustration-mamluk-lamps.jpg|Hagadá de Cataluña, s. XIV: [[Sinagoga]] |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Marror artichoke.jpg|[[Hagadá de Sarajevo]], manuscrito hebreo, s. XIV: "Maror zé" |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Illustration-haggadah-exodus.jpg|Hagadá de Cataluña, s. XIV: [[Moisés]] lidera el [[Éxodo]] |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Kennicott Bible 305r.l.jpg|[[Tanaj|Biblia Kennicott]], 1476, fol. 305r: [[Jonás (profeta)|Jonás]].<ref>[http://www.kennicottbible.org/ The Kennicott Bible]</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Book of Avodah (Service; on Temple Worship). Opening panel, folio 41v.The Israel Museum.jpg|''[[Mishné Torá]]'' ([[Maimónides]]), manuscrito italo-hebreo [[Renacimiento|renacentista]], ''c''. 1457, fol. 41v.<ref>[http://www.imj.org.il/exhibitions/presentation/exhibit/?id=929 Together Again: A Renaissance Mishneh Torah from the Vatican Library and The Israel Museum], Museo de Israel, mayo-septiembre de 2015.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:WLA_jewishmuseum_16th_century_Synagogue_Wall.jpg|[[Hejal]] de la [[Sinagoga]] de [[Isfahan]], [[Persia]], siglo XVI. Porción azulejada con inscripción hebrea.<ref>Preservada en el Jewish Museum de Nueva York.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Ketubbah David Immanuel and Rachel.jpg|''Ketubá'' (contrato matrimonial judío) del matrimonio Pinto, Italia, c. 1650-1700. [[Beth Hatefutsoth]], Tel Aviv.<ref>Acerca de la ''ketubá'' (כְּתוּבָּה; pl. ''ketubot''), véase [http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/art-ketubah-decorated-jewish-marriage-contracts Art of the Ketubah: Decorated Jewish Marriage Contracts ranging from the 17th to the 20th Centuries], ''Yale University'', Beinecke Rare Books & Manuscript Library, 2009 (accedido diciembre de 2013).</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Scribe- Nehemiah ben Amshal of Tabriz - Mūsā Nāma (The Book of Moses) by Mulana Shāhīn Shirazi - Google Art Project.jpg|Nehemiah ben Amshal de Tabriz, ''El Libro de [[Moisés]]'', manuscrito hebreo, 1686 |

|||

− |

|||

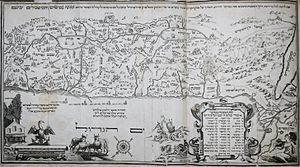

Archivo:1695 Eretz Israel map in Amsterdam Haggada by Abraham Bar-Jacob.jpg|'''Eretz Israel''' (ארץ ישראל) o "[[Tierra de Israel|La Tierra de Israel]]", con las [[Doce tribus de Israel|doce tribus]]. Mapa en hebreo por Abraham Bar Jacob, [[Hagadá|Hagadá de Ámsterdam]], 1695. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Scroll of esther.jpg|Rollo de [[Esther]] empleado en [[Purim]], Alsacia, 1730.<ref>Acerca del contexto histórico de este período véase Wachtel, [http://www.sothebys.com/en/news-video/blogs/specials/a-treasured-legacy-history-of-the-jewish-people/2013/04/jews-age-of-mercantilism.html The Jews in the Age Of Mercantilism], ''Sotheby's'', 3 de abril de 2013.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:YHWH Goya.jpg|[[Francisco de Goya]], "El nombre de Dios", [[YHWH]] (יהוה), detalle del [[tetragrámaton]] hebreo en un triángulo.<ref>El triángulo empleado por Goya tiene connotaciones tanto judías como cristianas, sugiriendo el componente divino de la [[Estrella de David]] así como también la noción de [[Santísima Trinidad]],</ref> representado en ''[[La adoración del nombre de Dios|La Gloria]]'', 1772. [[Catedral-Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza|Basílica del Pilar]], Zaragoza. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:May our eyes behold your return in mercy to Zion.jpg|[[Ephraim Moses Lilien]], ''Y nuestros ojos verán con piedad tu retorno a [[Sion]]''.<ref>La estampa es así titulada a partir de la inscripción en idioma hebreo que figura en la misma.</ref> Estampa para el Quinto Congreso Sionista, Basilea, diciembre de 1901.<ref>Imagen publicada en ''Ost und West'', Berlín, enero de 1902, [http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/cm/periodical/pageview/2585036 17-18].</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Design by El Lissitzky 1922.jpg|[[El Lissitzky]], ''Teyashim'', diseño para libro con texto hebreo, 1922. |

|||

− |

|||

File:Emblem of Israel.svg|Emblema del moderno [[Israel|Estado de Israel]], 1948 |

|||

− |

|||

File:PikiWiki Israel 19471 Sculpture quot;Ahavaquot; (love) by Robert India.JPG|Cuatro letras hebreas sugiriendo la palabra "amor" (אהבה) en hebreo. [[Robert Indiana]], ''Ahavá'', 1977. [[Museo de Israel]], [[Jerusalén]]. |

|||

− |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

− |

|||

− |

|||

== Estudio y traducción del idioma hebreo, diccionarios y concordancias == |

|||

− |

|||

<gallery widths=200 heights=200> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:St Pons de Thomières miséricorde.JPG|Talla medieval con monje inspirado por un ángel al traducir un texto bíblico del hebreo al latín. Sobre la imagen se encuentra incisa la siguiente inscripción: "אבינו שבשמים יהקדיש שמך" (''Avinu shebashamáim iheakdísh shimjá''), es decir, "Nuestro padre que [está] en los cielos santificará tu nombre". Misericordia gótica, Iglesia de St Pons de Thomières, Francia. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:1524 dictionary by Yuhanna al-Asad and Jacob Mantino Arabic-Hebrew-Latin p alif.jpg|Yuhanna al-Asad y Jacob Mantino ben Samuel, Diccionario árabe-hebreo-latín, 1524.<ref>Natalie Zemon Davis, ''Trickster Travels: A Sixteenth-Century Muslim Between Worlds'', Hill and Wang, 2006, pp.180-181.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Sefer Ha dikduk.jpg|[[Elias Levita]], ''Séfer Ha-Dikdúk'' o Libro de la gramática (hebrea), Basilea, 1525. [[Beth Hatefutsoth]] |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Mordechai nathan hebrew latin concordance.jpg|Mordejai Natan, ''Séfer Yair Natív'', concordancia bíblica hebreo-latina, Basilea, 1556. [[Beth Hatefutsoth]] |

|||

− |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

− |

|||

− |

|||

== Ejemplos de textos e inscripciones hebreas == |

|||

− |

|||

<gallery widths=200 heights=200> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Jewish oral law.jpg|Relieve con "mapa" de la tradición oral del pueblo judío: desarrollo en forma de río.<ref>Exhibido en [[Beth Hatefutsoth]] en 2011.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:058 Dafna Tal Susya SOUTH OF HEBRON IMOT (11965644446).jpg|Mosaico con inscripción de la Sinagoga de Susýa, Hebrón. |

|||

− |

|||

File:Elephantine Temple reconstruction request.gif|Yedoniah, Papiro con solicitud de reconstrucción de sinagoga, dirigida al gobernador de Judea, Elefantina, 407 a.E.C. |

|||

− |

|||

File:The Great Isaiah Scroll MS A (1QIsa) - Google Art Project-x4-y0.jpg|Sección del Gran Rollo de Isaías, siglo I a.E.C. [[Santuario del Libro]], [[Museo de Israel]], Jerusalén |

|||

− |

|||

File:Judeo-Persian letter BLI7 OR8212166R1 1.jpg|Carta hebrea, Persia, siglo VIII E.C. |

|||

− |

|||

File:192 Casa del Degà, inscripcions jueves i romanes.jpg|Tumba del rabino Jaim ben Isaac.<ref>La inscripción hebrea figura en el dintel superior, es soportada por otras dos en latín (cada una de estas últimas figura en un edículo).</ref> Antiga Casa Degà, Tarragona, Cataluña |

|||

− |

|||

File:Anonyme français - Inscription hébraique de Vidals Salomon Nathan - Musée des Augustins - RA 762 TER C.jpg|Lápida de Vidals Salomon Nathan, Francia, 1276-1300. [[Museo de los Agustinos]], [[Toulouse]] |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Schiefertäfelchen Archäologische Zone.jpg|Inscripción en hebreo lapidario, Sinagoga de Kalkstein, región de Colonia, Alemania, c. siglo XII o XIII. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Sefer-torah-vayehi-binsoa.jpg|Hebreo manuscrito. Asquenazí medieval. Fragmento de un rollo de la [[Torá]]. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Bodleian Bowl (Jewish Encyclopedia).jpg|Recipiente metálico, Francia o Inglaterra, siglo XIII.<ref>Conocido como el "Bodleian Bowl", perteneció al rabino Yechiel de París (''Jewish Encyclopedia'', 1901-6).</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Daiyyeinu manuscript.jpg|[[Hagadá]] de [[Pésaj]]. [[Arte asquenazí]]. Manuscrito medieval alemán, c. 1300.<ref>Original preservado en el [[Museo de Israel]], Jerusalén.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Cochin Jewish Inscription.JPG|Inscripción de la Sinagoga Pardesi, [[Cochín]], Kochangadi, India, 1344 |

|||

− |

|||

File:Eastern wall toledo synagogue.jpg|Fragmento mural con inscripciones en hebreo, [[Sinagoga del Tránsito]] ([[Toledo]], 1357-1363.<ref>La imagen muestra la réplica exhibida en [[Beth Hatefutsoth]] en 2011.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Song of songs Rothschild mahzor.jpg|El ''[[Cantar de los Cantares]]'' del rey [[Salomón]]. Majzór Rothschild, manuscrito italiano, 1492.<ref>Original preservado en el Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Nueva York.</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Cima da Conegliano - The Annunciation.jpg|Cima de Conegliano, ''La Anunciación'', c. 1500-18. [[Museo del Hermitage]], San Petersburgo |

|||

− |

|||

File:'Christ' by Quentin Metsys, c. 1529, oil on wood.JPG|Quentin Metsys, ''Cristo'', c. 1529. Porta la inscripción "יהשוה" (una de las varias formas del término Salvador). |

|||

− |

|||

File:Sefer Refu' at ha Geviyah, Judah Al Harizi.jpg|Yudah Al Harizi, ''Sefer Refu'at Ha'Geviyah'' (Libro de medicina), [[Salónica]], 1593. |

|||

− |

|||

Archivo:Rembrandt - Belshazzar's Feast - WGA19123.jpg|[[Rembrandt]], ''[[El festín de Baltasar (Rembrandt)|El festín de Baltazar]]'', 1635-38. |

|||

− |

|||

File:Rapaport Coat of Arms.jpg|Blasón y escudo de armas de la Familia Rapaport, Rapa, Italia, 1600 |

|||

− |

|||

File:Reyher.jpg|August Erich, ''Retrato de Andreas Reyher y su familia'', 1643. Castillo de Friedenstein. La leyenda presenta la inscripción חכמה ראשית יראת יהוה, significando que la sabiduría fundamental emana antetodo del Creador. |

|||

− |

|||

File:Chodorov Synagogue ceiling2.jpg|Israel ben Mordejai Lisnicki de Jaryczow, Cielorraso abovedado de la Sinagoga Jódorov (ingl. Chodorov), [[Galitzia]], Ucrania, 1652.<ref>David Wachtel, "[http://www.sothebys.com/en/news-video/blogs/specials/a-treasured-legacy-history-of-the-jewish-people/2013/04/eastern-europe-jews.html The Jews of Eastern Europe]", ''Sotheby's'', 3 de abril de 2013 (accedido 11 de noviembre de 2013).</ref> |

|||

− |

|||

File:Megillat Esther 2.l.jpg|Fragmento de [[Purim|Rollo de Ester]], Alemania, c. 1700.<ref>Original preservado en la colección Gross, Tel Aviv ([http://www.facsimile-editions.com/en/me/ Megillat Esther], consultado 12 de febrero de 2015).</ref> |

|||

File:Reichshoffen-Ancienne synagogue (3).jpg|Sinagoga de Reichshoffen, Bajo Rin, Francia |

|||

File:Ketuba yemen 1795 2.jpg|''Ketubá'' (contrato matrimonial hebreo), Sa'ana, Yemén, 1795 |

|||

File:Sinagoga Mare din Harlau1.jpg|Éxodo 25:8. Sinagoga Mare din Harlau, Rumania, 1814 |

|||

Archivo:JudischerKalender-1831 ubt.jpeg|Calendario judío-alemán, Berlín, "5591" = 1831 E.C. |

|||

File:Torah ark curtain - Google Art Project.jpg|''Parojet'' o cortinado del [[Arón Ha-Kodesh]], Praga, 1853. [[Museo de Israel]], Jerusalén |

|||

File:Vitrail de synagogue-Musée alsacien de Strasbourg.jpg|[[Los diez mandamientos]]. Vitral de la Sinagoga de Estrasburgo, siglo XIX− |

|||

File:Synagogue plaque Sibiu.jpg|Abraham Pavian, Placa con horario de oraciones y versos de Salmos 88:13-17, Sinagoga de Sibiu, Rumania, 1871 |

|||

File:Rosh hashana vilna.jpg|Portada del Tratado de [[Rosh Hashaná]]. [[Talmud]], Vilna, 1881 |

|||

Archivo:Chalons Marne Synagogue Verset.jpg|Inscripción con el Salmo 84 sobre la fachada de la Sinagoga de Chalons Marne. |

|||

File:Kafka's notebook.JPG|Cuaderno de Franz Kafka con vocabulario hebreo traducido al alemán |

|||

File:Academy of the Hebrew Language.JPG|[[Academia del Idioma Hebreo]], [[Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén]] |

|||

File:Door of Four Sephardi Synagogues (2667016779).jpg|[[Arte sefardí]]. Puerta de la [[Las cuatro sinagogas sefardíes|Sinagoga Yohanan Ben-Zakai]], Jerusalén, c. 1970-85 |

|||

Archivo:Happy Cake.jpg|Torta con la inscripción מזל טוב (Mazal Tov) en letras cursivas, expresando tanto "buena suerte" como "felicidades". |

|||

File:Hebrew- Do not hate your brother in your heart.jpg|Pancarta con la inscripción ־ לא תשנא את אחיך בלבבך "No odiarás a tu hermano en tu corazón", Ashdod, 2013 |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

Revisión actual - 07:46 30 may 2022

Esta es mi zona de pruebas. Es subpágina de mi página de usuario y me sirve para hacer pruebas. Ella no es un artículo de la enciclopedia. Solicito no modificarla. Gracias, Calimeronte

Cita literal de imagen en Commons[editar]

Planchas sobre la Inquisición en Caprichos 23 y 24, con personajes vestidos con sambenito y titulados ellos Aquellos polbos y No hubo remedio. En sus apuntes (Álbum C, 1803-24), Goya expresa su resentimiento hacia la Inquisición. Allí, muchas de las imágenes están comentadas o tituladas explicando la causa de lo que ocurre: Por haber nacido en otra parte, Por linaje de ebreos, Por mober la lengua en otro modo, Por casarse con quien quiso, etc. señalando la frivolidad con que la Inquisición perseguía a sus víctimas. La visión de Goya con respecto a la Inquisición ya había cambiado. De ser una institución anticuada, que se asienta sobre supersticiones y un pueblo ignorante, una institución específicamente española, pasa a convertirse en un símbolo de la injusticia universal.

A verificar[editar]

- Arte sefardí

- Sefarad, Hagadá, Hagadá de Sarajevo, Dayenú

- Arte judío, Cultura judía, Beth Hatefutsoth, Museo de Israel

- * Museo de Israel, Jerusalén — Colecciones del Departamento de Judaica: Manuscritos hebreos miniados,Implementos Sinagogales, Sinagoga de Alemania, Sinagoga de India, Sinagoga de Italia, Sinagoga de Surinam, Vestimenta e Indumentaria Etnográficas, Ciclo de la Vida: Nacimiento, Esposorios, Defunción, Shabat, Pésaj y Sucot, Janucá y Purim.

- Museo de Arte y de Historia del Judaísmo, París

- Museo de Arte Judío, Nueva York

DATUM[editar]

Mishné Torá = código legal

- Mishné Torá, 1342. Sefer Ahavah. a skilled non-Jewish artist of Perugia by the name of Matteo di Ser Cambio. Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem, Heb. 4* 1103. 14th century. A page with a decorated title-panel of Sefer Ahavah (Book of Love) from the second book of the Mishneh Torah. Spain and Italy, 14th century. This is one of the most elaborately decorated manuscripts of the Mishneh Torah. In the absence of a colophon, it can be inferred from the script that the manuscript was copied either in Spain or southern France in the first half of the 14th century (in any case, before 1351, when the codex was sold in Avignon). The scribe's name was probably Isaac, since this name is decorated in several places in the text. The manuscript was illuminated in burnished gold and lively wash colors by a skilled non-Jewish artist of Perugia by the name of Matteo di Ser Cambio. Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem, Heb. 4* 1103 [2] - foto y datos JUNL. El libro fue escrito entre 1300 y 1350, luego miniado en Sefarad y hacia 1400 con iluminaciones realizadas por un artista del taller de Mateo Di Ser Cambio proveniente de o en Perugia.

- Guía de los Perplejos, Barcelona, 1348. Facsimile of a page from Maimonides' great philosophical work Moreh Nevukhim (Guide of the Perplexed) written originally in Arabic and here in the Hebrew translation of Samuel ibn Tibbon (ca. 1160-1230) copied and illuminated in Barcelona, 1348. The seated figure is holding an astrolabe. Royal Library, Copenhagen, Cod. Hebr. XXXVII, fol. 114r [3]

- Mishné Torá, Lisboa, 1472. Facsimile of the colophon of the Lisbon Mishneh Torah written by the scribe Solomon ibn Alzuk and completed in 1471-72. The British Library, London, Harley Ms. 5699, fol. 434v. [4]

- Golden Haggadah. "The Golden Haggadah, one of the finest surviving Spanish Hebrew manuscripts, was made near Barcelona in Northern Spain. The Haggadah, which literally means ‘narration’, is the service-book used in Jewish households on Passover Eve to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt. The text is preceded by a series of full-page miniatures depicting scenes mainly from the Book of Exodus. These sumptuous illuminations set against gold-tooled backgrounds earned the manuscript its name and were executed in the northern French Gothic style" BL + "The Golden Haggadah is one of the finest of the surviving Haggadah manuscripts from medieval Spain. The Haggadah, which literally means 'narration', is the Hebrew service-book used in Jewish households on Passover Eve at a festive meal to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt. | It is one of the most frequently decorated Jewish books. The fact that it was intended for use at home with its main aim being to educate the young, provides ample scope for artistic creativity. | The Golden Haggadah was probably made near Barcelona in about 1320. In addition to the Haggadah text itself the manuscript contains liturgical Passover poems according to the Spanish rite. The text is preceded by a series of full-page miniatures depicting scenes mainly from the Book of Exodus. These sumptuous illuminations set against gold-tooled backgrounds earned the manuscript its name and were executed by two artists in the northern French Gothic style. | The 17th-century Italian binding has an elaborate border on each cover. Hebrew is written from right to left, so the Golden Haggadah opens from the right. British Library Add. MS 27210 BL Virtual Bk Images Only

IMAGO[editar]

-

Mishné Torá:Sefer Ahavah, Sefarad-Perugia?, 14th century - c. 1342 INUL

-

Arba ha-Turim, Sefarad, c. 1350. Gótico internacional, escuela lombarda. Véase Gutmann, Hebrew Ms Ptg, 1979, 27:XVI.

-

Mishné Torá: Sefer Mishpatim, c. 1457. semi-cursive Ashkenazic script. IMJ

-

Hagadá de Venecia, 1609. Impresa por Giovanni di Gara e Israel ben Daniel ha-Zifroni. IM

-

Meguilat Ester, Italia, 1616. INUL

Menorah. Illuminated leaf with illustration of the Menorah. IM. Spain, Late 15th century. Since the Temple’s destruction, depictions of its seven-branched candelabrum (Menorah) have served a symbol of the Temple and of redemption. Medieval Hebrew manuscripts contain many portrayals of the Menorah alongside other Tabernacle and Temple vessels. In Spain and Provence, these were especially profuse, and the Bible codex was sometimes called a Mikdashyah (God’s Temple). This single leaf, probably part of a manuscript, shows the Menorah symmetrically flanked by tongs, incense shovels, and the three-stepped stone on which, according to the Mishnah, the priest stood to trim the lamp.

Sefer Mishpatim (enlace escrito desde commons). Facsimile of a page with a decorated title-panel of Sefer Mishpatim (Book of Civil Law) from the 13th book of the Mishneh Torah, northern Italy, 15th century. In the bottom register three men stand before a panel of four seated judges. The top register consists of a jousting scene that is unrelated to the text. Private collection, fol. 298v. [5]

Commons categories[editar]

en:Category:Hebrew_manuscripts,_Wellcome_Collection Heb Mss Wellcome Coll.

Sefarad

Hagadá Kaufmann, Cataluña, S. XIV

Hagadá Rylands, Cataluña, s. XIV. John Rylands University Library, Manchester

Hagadá Sarajevo, Barcelona, 1350 - Hagadá de Sarajevo

Asquenaz

Mishné Torá Kaufmann, Fr, 1290

en:Category:Hebrew_calligraphy Hebrew callygraphy

LINKS n ARTICLES[editar]

Burgos 1260 (JNL Damascus Keter)

JTS Treasures Prato Haggadah JTS Prato Haggadah - facsímil Prato Hagadah 2006

David Kaufmann. Mss. miniados hebreos del medioevo . En la Biblioteca de la Academia Húngara de Ciencias. - versión castellana. - folios; Hagadá catalana (MS A 422); A; B; Mishneh Torah fr (MS A 77); artistas; profanidad | Mahzor (MS A 384); zodíaco; ver también: mishné torá fr 1296 (Ms A 77) y Majzor de-sur 1320 (Ms 384)

-

Damascus Keter, Burgos

-

The Kaufmann Haggadah (MS Kaufmann A 422) was produced in 14th century Catalonia. It contains the prayers, poems and narrative texts to be recited on the eve of the festival of the Jewish Easter, Pesach, the Feast of the Passover. fol. 13r

-

Majzor (tripartito) 1320

-

Mishneh Torah (Maimonides), North-Eastern France, 1296. Kauffman Ms. 77a, fol. 046v.[1]

Yale

- IM: Judaica

- IM: ILL MSS

- Hagadot manuscritas

- Expo Maimónides at Yale

- Maimónides Ill. Mss. at Yale

- hagadot impresas

- libros impresos siglo XV

- idem siglo XVI

- hagadot modernas

- hagadot IL

McBee jewish art definition sarajevo rylands 1 rylands 2 rylands in context ES synagogues

Heb Mss S Collection Pins Heb Mss Russian Collection Pins Superfine Judaica French Collection Pins Sefarad Pins Haggadah Pins Judaica

BL Virtual Books : Accesible Golden Haggadah - Golden Haggadah - Lisbon Bible - Vesalius

Prato Hagadá[editar]

JTS Treasures facsimil eds historia expo con datos

JWS MS[editar]

Hungarian Academy of Sciences: Kaufmann Collection

Schechter Institute on Akedah[editar]

Prior to the 1930`s, most scholars were convinced that ancient Jewry produced no art. As a result, the discovery in 1932 of the biblical wall-paintings decorating the third century synagogue of Dura Europos,Syria stunned the academic world. In these earliest extant examples of Jewish art (antedating comparable Christian art by two centuries) the community expresses its acceptance of pious rabbinic midrashim. Center stage above the Torah ark, a naively drawn Abraham stands firm before the altar, knife raised, his back to the viewer. Dura Europos Synagogue, Akedah (detail), 244 C.E.

he saving ram is tethered behind Abraham awaiting its theological moment. Tiny Isaac is impaled upon a monumental altar (see the Midrash in Targum Yonatan, below). He too looks away from us, as does Sarah (rarely represented in akedah scenes) in the doorway of her tent, the highest and most distant point of the scene. They are all focused on the hand of God, "the Place from afar" at Moriah (v.3), identified in late biblical times as the site of the once and forever restored Temple of Jerusalem. 170 years after its destruction, the Temple and its implements are visually restored at the center and left of this scene, together with the akedah, the symbols of Diaspora hope for national and religious restoration. Dura Europos Synagogue, Akedah

Just three years prior to the discovery of Dura, a stunning mosaic floor of a 6th century synagogue had been uncovered at Kibbutz Bet Alpha., the earliest akedah to be found in Israel. The naive style of the mosaic displays Jewish, pagan and possibly Christian elements. On entering the synagogue, the worshiper first encountered the akedah, a focal narrative of Jewish tradition. The worshiper next saw a zodiac, centered on the sun god Helios and his chariot. Is this a synagogue? It is likely that these pagan symbols were interpreted as representing the ritual calendar of the congregation - but, it is also evidence of a Judaism culturally alive to the imagery of the Greco-Roman Byzantine heritage. Finally, in the third section, closest to the holy ark, the worshiper saw (as in Dura) the doors, menorah and ritual tools of the restoredTemple. Left: Bet Alpha Synagogue, Entire Floor

Above right: detail, Bet Alpha Synagogue, Akedah, 6th century: The playful color patterns and paper-doll character of the figures belie the theological intensity of the akedah scene. The two servants stand at the left, together with the ass (v. 5). At the center point, the ram hangs from a bush, rather than being caught in the thicket, as recounted in the Bible (v. 13). Above, a haloed hand of the angel "calls out": Do not raise [your hand] (v. 11 – 12). On the right, the child Isaac is held aloft between Abraham and the burning altar (v. 10). The artists altered the sequence of the story by placing the ram at center stage. Thus the mosaic seems to focus on God’s compassionate substitution of Isaac by the ram, rather than on Abraham’s extraordinary act of faith. It has been suggested that the hanging ram is based on Christian iconography, connecting Isaac, the ram and Jesus as parallel sacrifices. But just as in the use of the pagan zodiac, the borrowing of this model does not imply a heterodox interpretation, but rather cultural contact.

In 1947, Mordecai Ardon paints the worst scenario. Isaac lies dead at Sarah’s feet, his mother a large, grotesque weeping figure, screams the call of the shofar. Parallel and opposite the fallen Isaac, a fallen ladder of Jewish continuity conveys two dead ends: Jacob’s ladder, that will not be, and the train tracks to Auschwitz. The faceless mother and child echo the universal pieta motif, the mother holding her deceased child, whether in antiquity or in our times. M. Ardon, Sarah, 1947

A traducir e incluir[editar]

fuente fechada 20.8.2011, 6.7.15

O idioma hebraico (עברית, ivrit) é uma língua semítica pertencente à família das línguas afro-asiáticas, o termo semítico determina que bem como o árabe e o persa, sua orígem é um tanto desconhecida. As primeiras bases da Bíblia, a Torá, que os judeus ortodoxos consideram ter sido escrita na época de Moisés, cerca de 3.300 anos atrás, foi redigida no hebraico chamado de "Hebraico Clássico".

Embora hoje em dia seja uma escrita foneticamente impronunciável, portanto indecifrável, devido à não-existência de vogais no alfabeto hebraico clássico, os judeus têm-na sempre chamado de לשון הקודש, Lashon haKodesh ("A Língua Sagrada") já que muitos acreditam ter sido escolhida para transmitir a mensagem de Deus à humanidade.

Após a primeira destruição de Jerusalém pelos babilônios em 586 a.C., com o retorno dos judeus para a Terra de Israel, o hebraico clássico foi substituído no uso diário pelo aramaico, tornando-se primariamente uma língua regional, tanto usada na liturgia, no estudo do Mishná (parte do Talmude), bem como também no comércio. Sendo que nos dias de Yeshua(Jesus), este idioma clássico ainda era falados sacerdores, levitas, saduceus e os fariseus doutores da lei, mas o povo em geral utilizava o Aramaico como idioma no dia a dia.

Após a destruição de Jerusalém no ano 70 DC, os judeus foram aos poucos expulsos da Terra de Israel, os que ficaram sofreram influencia dos muitos povos que dominaram na região e o Hebraico deixou de ser utilizado como idioma nacional, passando ser utilizado apenas em liturgias religiosas.

O hebraico renasceu como língua falada durante o final do século XIX e começo do século XX como o hebraico moderno, adotando alguns elementos dos idiomas árabe, ladino, iídiche, e outras línguas que acompanharam a Diáspora Judaica como língua falada pela maioria dos habitantes do Estado de Israel, do qual é a língua oficial primária (o árabe também tem status de língua oficial)

1) Hebreo clásico. http://www.cafetorah.com/portal/Hebraico-Biblico-Hebraico-Classico

Hebraico bíblico, também chamado de hebraico clássico, é a forma arcaica da língua hebraica, uma língua semita falada na área conhecida como Canaã, entre o Rio Jordão e o Mar Mediterrâneo. Hebraico bíblico é conhecido por volta do século 10 AC, e persistiu durante todo o período do Segundo Templo (que termina em 70 dC). O Hebraico bíblico tornou-se eventualmente hebraico Mishnaico que foi usado até o segundo século EC.

O Hebraico bíblico é mais bem utilizado na Bíblia Hebraica, a Bíblia é um documento que reflete vários estágios da língua hebraica em sua forma consonantal, bem como um sistema vocálico que foi adicionado mais tarde, na Idade Média. Há também algumas evidências de variação dialética regional, incluindo as diferenças entre o hebraico bíblico falado no Reino do Norte de Israel e no Reino do sul, o Reino de Judá.